Google’s recent action of redirecting google.cn traffic to servers in Hong Kong has raised much comment. Google’s claim is that it is doing this so it doesn’t have to follow Chinese government demands to censor what it has online.

The Chinese government, in its turn, has stated that it has the right to set the rules by which a corporation functions in its country.

In the process of this dispute, the diverse views of the Chinese internet users, of its netizens, appear to be missing from Google’s considerations.

Some netizens in China posted an Open letter to Google and to the Chinese government ministries, asking that each side in the dispute present in an open way what their views are, so that the netizens can be part of the discussion and decision-making process determining what should happen.(1)

Google has ignored this request. It has done what it decided to do. It claims that this is its good deed for the world. But is it? Is Google acting with concern for netizens in China? The authors of the Open Letter objected to the secret manner in which Google has acted to make its decision.

This situation is reminiscent of an experience that users of what is known as “Usenet” had with Google almost 10 years ago. In 2001, Google acquired from another company, from Deja.com, an archive of posts put on Usenet by its users. Deja was going out of business and allegedly sold the Usenet posts it had archived to Google.

At the time a number of users of Usenet were surprised that the posts they had contributed to Usenet discussion groups had been sold from one company to another. Also at the time there were concerns about what Google might be planning to do with the posts.

An effort was made to ask Google to recognize that Usenet itself had grown up as part of a cooperative online community of users who contributed their efforts and articles to help to enrich this online community.

There was a concern among users on Usenet. Would the forms of participatory decision-making in this online community, which had been developed to involve users, be lost when a corporation like Google got involved in owning and controlling the archives of Usenet posts? Google was asked to contribute the archive or a least a copy of the archive, to a public entity that could protect it.

At the time, Google ignored these requests. Instead Google even began putting a copyright symbol on the articles in the archive, claiming that Google owned the copyright to the many contributed posts. This was contrary to the Berne Convention, the law regarding such posts. The Berne Convention, which the US agreed to respect as its copyright law as of March 1, 1989, provides that the posts were the property of the users who had created them, not of Google.

Eventually Google stopped putting its copyright symbol on Usenet posts. This took quite a while, however, despite the fact that the illegal nature of Google making such a claim had been pointed out to Google soon after it started to post its copyright symbol on Usenet users posts.

The significant point of the experience that I and other Usenet users had with Google, however, is that we found that Google acted according to its own interests and its own directives. Management at Google refused to respond to users‘ concerns. In the process of this struggle I wrote an article titled “Culture Clash” which appeared on February 26, 2001 in the online magazine Telepolis describing what was happening with Google. (2)

In response to the article, I was invited to give a talk at Stanford University in California, where Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the creators of Google, had done their research on the search engine algorithm that was the basis for the Google search engine. I was told I would have a chance to debate what I had written in my article with Brin and Page at a program at Stanford. Once I arrived at Stanford, however, I was told that they would not be part of the program. Instead I could give the talk without them at Stanford and then go and speak at the corporate headquarters of Google.

I gave a talk at Stanford and then went to Google’s Mountain View headquarters and gave the talk a second time. While I appreciated having the chance to speak to, and afterwards have a discussion with, some of those working at Google at the time, neither Brin nor Page were available to participate in the program or to talk with me. Instead the person I was told I could speak to, offered no means for Usenet users to make input into the decisions-making process of Google.

Based on my experience with Google, I wrote the article “Commodifying Usenet and the Usenet Archive or Continuing the Online Cooperative Usenet Culture?” (3) The article was published in the scholarly journal “Science Studies” in January 2002.

In the article I described how Usenet had been created by a cooperative online process. One example I gave, was when one of the pioneers involved in early Usenet development wanted to change the name of Usenet. He proposed this change to the users of Usenet. After an extended discussion it became clear that many users disagreed. The plan to change the name of Usenet was dropped. The name remained as Usenet. There were a number of other similar examples in the early days of Usenet development where users were involved in the discussion of problems and in contributing to the decisions that were made.(4)

This was, however, no longer to be the case when Google became involved with Usenet. As a result, some aspects of Usenet have survived, especially the discussion groups dealing with technical issues. A number of other discussion groups that existed on Usenet, however, were negatively affected by the ways that Google and other companies began to make various decisions, not only with respect to how Usenet was archived or searched, but also affecting other aspects of Usenet.

In trying to understand what has happened as the corporate world represented by Google and other online services began to affect the online world and the experience of netizens in this online world, it is helpful to also keep in mind Google’s own origins.

When Brin and Page were students at Stanford University working on their search engine project, they wrote a paper criticizing the commercialization of search engine research. In the paper, they proposed the need for an open laboratory approach to working on search engine design. Such an approach would allow the best results to be developed and built by the research community. Brin and Page criticized the commercial decision making processes, particularly the secrecy, lack of community input into the processes and focus on advertisements. They criticized that this had caused „search engine technology to remain largely a black art and to be advertising oriented.“ (5)

The project that Brin and Page were part of had National Science Foundation (NSF) funding. US government funding during this period of the late 1990s took a turn toward promoting commercialization as opposed to supporting basic research in science and technology. The Director of the NSF, Dr. Rita Colwell, explained to the US Congress that the „transfer to the private sector of ‚people‘ – first supported by the NSF at universities – should be viewed as the ultimate success“ of the US government technology policy.(6)

The significance of this change was that Brin and Page became connected with the same „black art“ they had critiqued as graduate students. The objectives of the Google corporate structure is not to facilitate the sharing of ideas and the communication that facilitates the best design of search engine technology that were the objectives Brin and Page advocated as researchers at Stanford.

More seriously, the vision of the Internet as a place where netizens strive to understand the problems that develop, and work together to find the solutions that will continue to foster an environment facilitating communication, is a vision that corporate entities do not share. Hence the culture clash that developed between Google and the Usenet community. Keeping in mind this persepective it is helpful to look at what Google is doing with respect to netizens in China.

The situation with regard to China’s online world is one in which there are many important discussions online among netizens. Many of China’s netizens contribute to serious discussions on issues concerning the problems in China and the world.(7) In the process they have often been able to have an impact on what government officials in China do. This is an important development with respect to the Internet, a development that other netizens around the world can learn from.

Instead of Google learning from what is happening in China and trying to hear what China’s netizens are saying about Google’s concerns and plans, Google is making decisions which affect netizens in China without involving them in its decision-making processes.

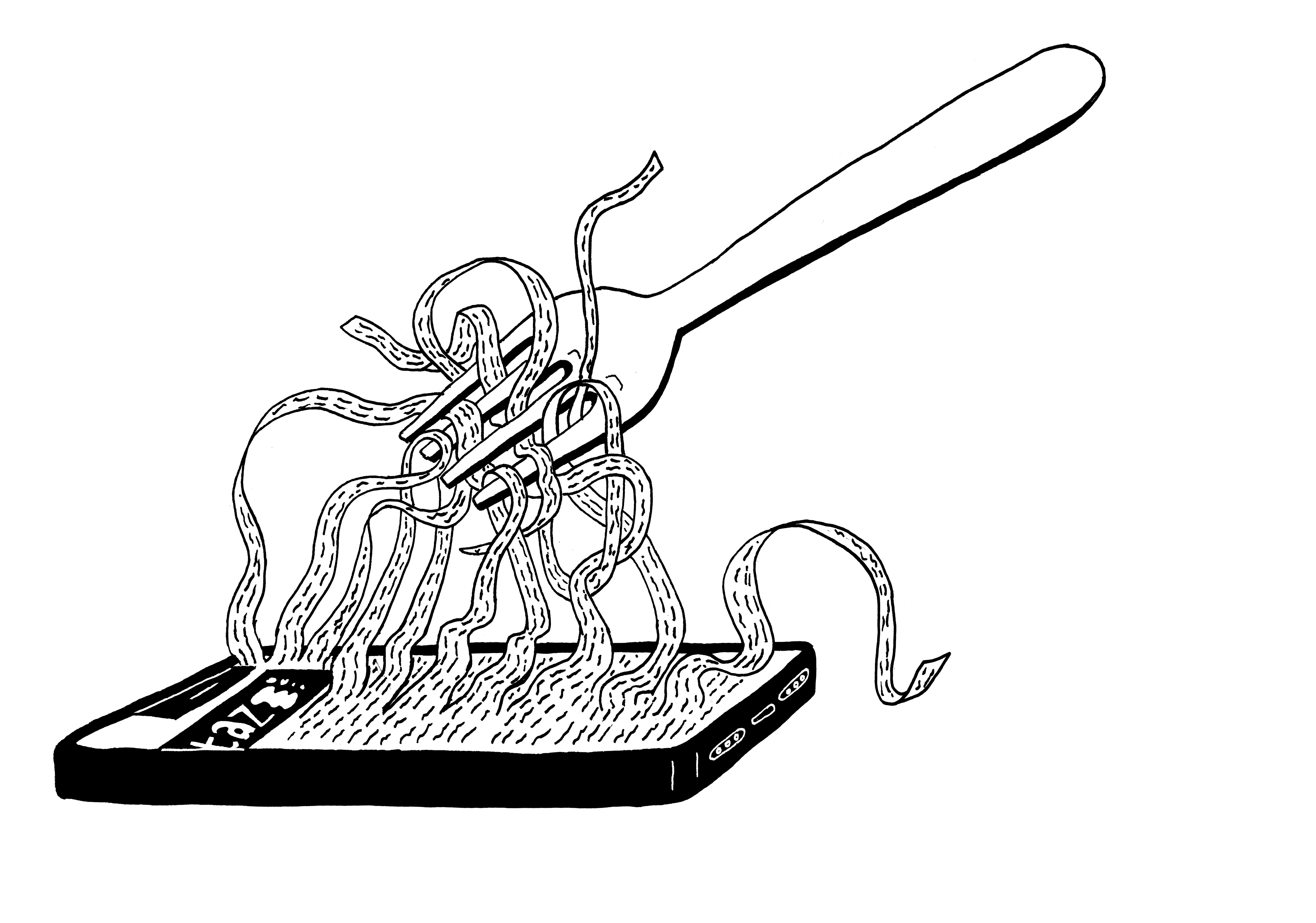

Unfortunately, many users around the world have become dependent on Google for many of their Internet activities and are thus at the mercy of but another corporate entity that does not care for the development of the kind of cooperative communication that the Internet and netizens have nourished and endeavored to spread more broadly and widely.

What is happening in the struggle between Google and China therefore is important. Google claims it cares for online users in China, but there is no evidence that Google has seen any reason to consider the views and concerns of China’s netizens. Thus Google’s decision to redirect its google.cn traffic to servers in Hong Kong is but the decision of another corporation acting on the claim that the corporation knows best. Thus the culture clash between netizens and Google continues.

Notes

(1)Chinese netizens‘ open letter to the Chinese Government and Google

Draft for discussion

Version: 0.99

March 2010

To the relevant Chinese government ministries and Google Inc.,

http://docs.google.com/View?docid=dfw7fpm7_77crfpc8fv

2.Ronda Hauben, „Culture Clash:The Google Purchase of the 1995-2001 Usenet Archive And the Online Community“, Telepolis, February 21, 2001.

http://www.heise.de/tp/english/inhalt/te/7013/1.html

3.Ronda Hauben,“Commodifying Usenet and the Usenet Archive or Continuing the Online Cooperative Usenet Culture?“,Science Studies 15:(2002),

p.61-68.

http://www.columbia.edu/~rh120/other/usenetstts.pdf

4.Ronda Hauben,Early Usenet(1981-2) Creating the Broadsides for Our Day.

http://umcc.ais.org/~ronda/new.papers/usenet_early_days.txt

5. Sergey Brin and Larry Page, „The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine“,

http://infolab.stanford.edu/pub/papers/google.pdf

6. http://www.nsf.gov/od/lpa/congress/106/rc00504approp.htm

7. Ronda Hauben,“China in the Era of the Netizen“, in Netizenblog.

http://blogs.taz.de/netizenblog/2010/02/14/china_in_the_era_of_the_netizen/