Just came back from a visit in Israel (it was February, 31 degrees and everyone was at the beach—no wonder all three religions are willing to kill to have this place), where I had an extended conversations with my niece—she is 14 going on 20- about her life, growing up, Facebook, and how does she sees the situation.

She told me two stunning things. The first was about her trip to Barcelona and how she felt so unsecured that she forced herself to wear a coat over her t-shirt that was emblazoned with some Hebrew words. “It’s weird to know that everyone hates you”, she told me. I tried to comfort her by telling her that when I was 14 I also thought that the entire world hates me, but I knew it wasn’t the same.

The second thing she told me shocked me even more. She was telling me that her real fear is not the Iranian bomb, the missile from Lebanon or suicide bombers from the West Bank, not even the pimples that started to build a settlement around her cheeks. “The violence in the streets, in our school, the violence every where. That’s what really scares me”.

I looked at the police reports and statistics from the past five years, and by sheer numbers one can’t really trace the increasing violence in Israel. But it is not in the numbers, but rather in the cruelty of the acts and by how cheap life became in Israel that you could feel the unease walking the street, driving the car, waiting in line.

A sample from just the last couple of months: one man murdered three generation of one family and set their house on fire after he was fired by the father from his workplace; a 12-year-old stabbed his 10-year-old sister after she insisted on turning on the fan in their room; a young mother was murdered on the beach near Tel Aviv after two groups were shooting at each other; a family man was beaten to death for no reason by some young people while walking on the Tel Aviv boardwalk; a teenager was murdered over an argument over a cigarette, another one over an argument over a parking space.

Every time I went out this past vacation my mother reminded to not argue over anything. One guy skipped the line in the bank and my friend forbade me from lecturing him. People are losing their nerves over anything. At some point I started to think where all of this is coming from.

I will start by saying that, given the fact that so many Israelis are carrying weapons legally, Israel haven’t reached an American level of violence, but as I have already written it is not in the numbers, but in the atmosphere. I think that partially it has to do with Israel maturing into itself (crime, unfortunately is one aspect of a maturing community), part of it is the screaming headlines in the newspaper, a major impact is the increased alcohol consumption and its availability, and most certainly, the continuous tension with our neighboring countries doesn’t help relax nobody’s nerves.

But the more I am thinking about it, I keep finding myself remembering something that happened to me exactly 20 years ago. I remember it very clearly as it happened one day after the collapse of the Berlin wall. It was a Friday and we were awarded a weekend vacation from our army service. We were young soldiers serving for a month in Nablus. It was in the height of the first Palestinian uprising, and my friend told me that I must join him for a warm meal. Since he was living nearby and the prospect of spending the few hours I got on traveling the roads to my house didn’t appeal to me, I took him for his offer.

When we arrived, he hugged his family, we hid our rifles in his room, took a shower and sat on the table. He ordered his little sister to pick up our clothes to the laundry, to clean after us in the bath and then asked her to see what is going on with the soup. I knew him from our first day in the army and we became friend right away. He had a gentle soul and his behavior shook me with surprise. When the soup bowls came we took one sip and my friend completely lost it. He threw his bowl on the floor with anger and was screaming in the general direction of the kitchen that “if I wanted cold soup I would stay in the base”.

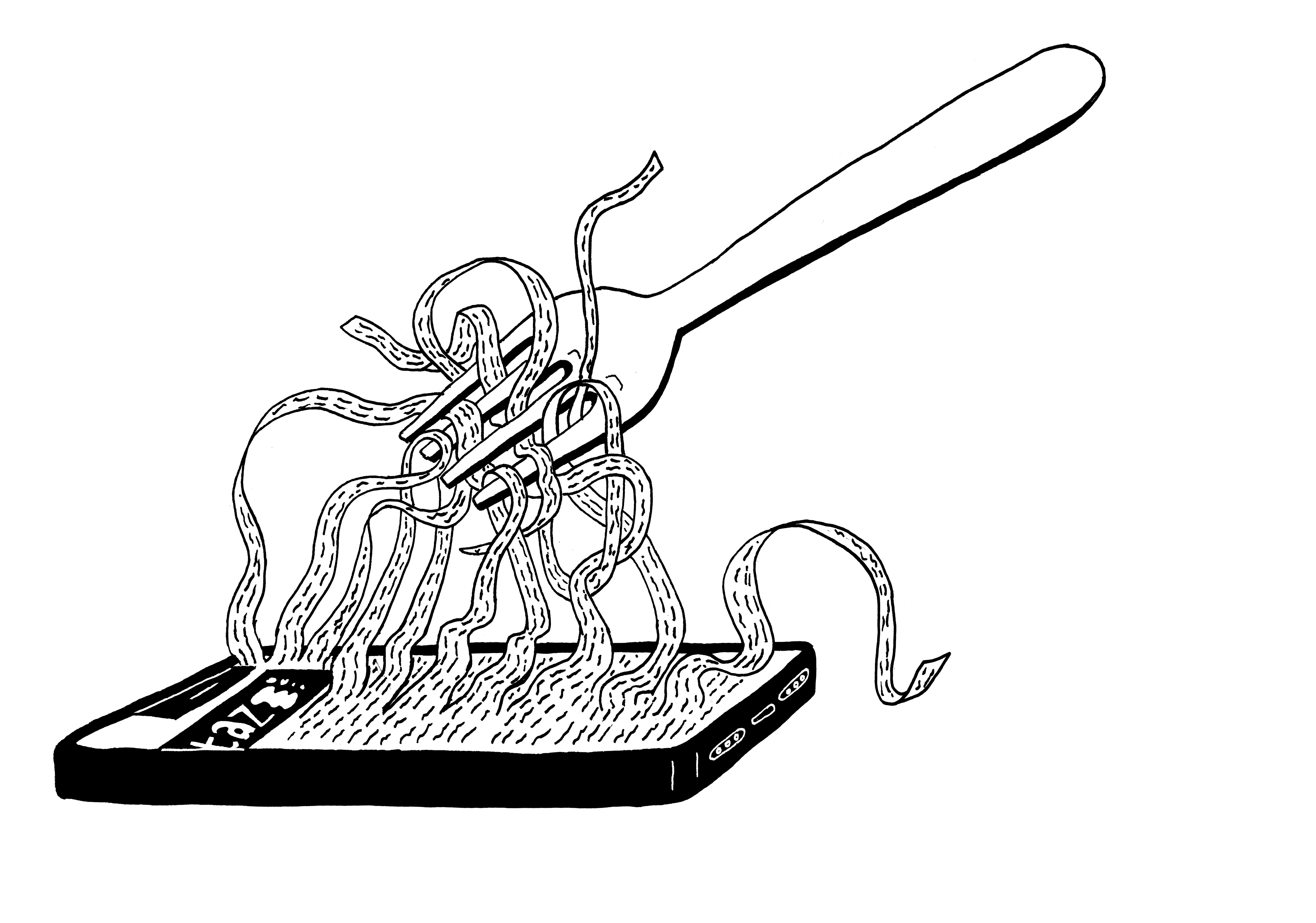

One day later, as I was hitchhiking my way to my parents’ house, I was thinking about this a lot. Actually I never stopped thinking about it since. It was the first time that I personally encountered how the occupation occupied our life, our souls, our nervous system. I remember thinking about how what happen there can never be locked and stay there. That all of this telling people what to do, when to be home and when they can go out and work, the absolute power of controlling people’s life, having them answer our orders without any argument, someone must be very naïve to think that we could have leave it in the Western Bank and the Gaza strip, return to Israel, declared it on the red path of the custom, and be normal, accept a negative answer, a refusal, a contest to one’s wishes.

There is no easy solution for this situation. It must start with the acknowledgement that the ongoing Israeli occupation is a national suicide. It should go on with leadership that can steer Israelis to a new road. Israeli leaders in recent history were too busy covering their legal problems (the spreading corruption is another tumor brought by the cancerous occupation), or patching temporary solutions to problems, finding that their blanket is always too short to cover it all. What Israel need is a leadership that can sell and promise its residents new vision and hope.

I believe that that’s what Israel miss more than anything—vision and hope. Someone’s crazy enough to think about the next step, just like Jewish leaders were crazy enough to think about Israel as the state for Jews early in the 20th century. I can live peacefully with the notion of some Arabs who wants to throw the Israelis into the sea—at least it is a clear vision. Our window to the future is so rotten we can’t see one day ahead anymore.

They say that hope is the last thing you lose before you die. Jews had a common hope for thousands of years: “for next year in Jerusalem”, they used to bless each other. This hope has been fulfilled—Jews can be in Jerusalem now within a day, hour, they can even live in Jerusalem. It is time for a new hope, it is time to prove that Oscar Wilde quote that “When the Gods wish to punish us, they answer our prayers” is wrong. Otherwise we are just killing ourselves.