Zu den wenigen intellektuellen Aushängeschildern in dieser an Intellektualität abgespeckten Stadt Wien gehört die theaterwissenschaftliche Vierteljahresschrift Maske und Kothurn. Schon der sperrige Titel des Periodikums ist Programm. In der neuen Ausgabe, verantwortet von Michel HÜTTLER und durchgehend in englischer Sprache, geht es um neue Forschungsergebnisse zu Leben und Werk des Hoftheaterdichters und Sprachlehrers Lorenzo Da Ponte [1749-1838].

Der in Venezien geborene und in New York verstorbene Da Ponte gehört zu den schillerndsten Figuren der mit spektakulären Auftritten ohnehin verwöhnten Wiener Mozartzeit. Beiträge liefern u.a. H. E. WEIDINGER und Herbert LACHMAYER, der vor zwei Jahren die grosse Mozartausstellung in der Albertina vergeigt hat.

Aus dem Band heraus ragen zwei Texte des Berliner Religionsphilosophen Klaus HEINRICH, von denen sich der erste mit Librettologie (Musiktheaterdichtung) und der zweite mit Sammlungsgeschichte beschäftigt.

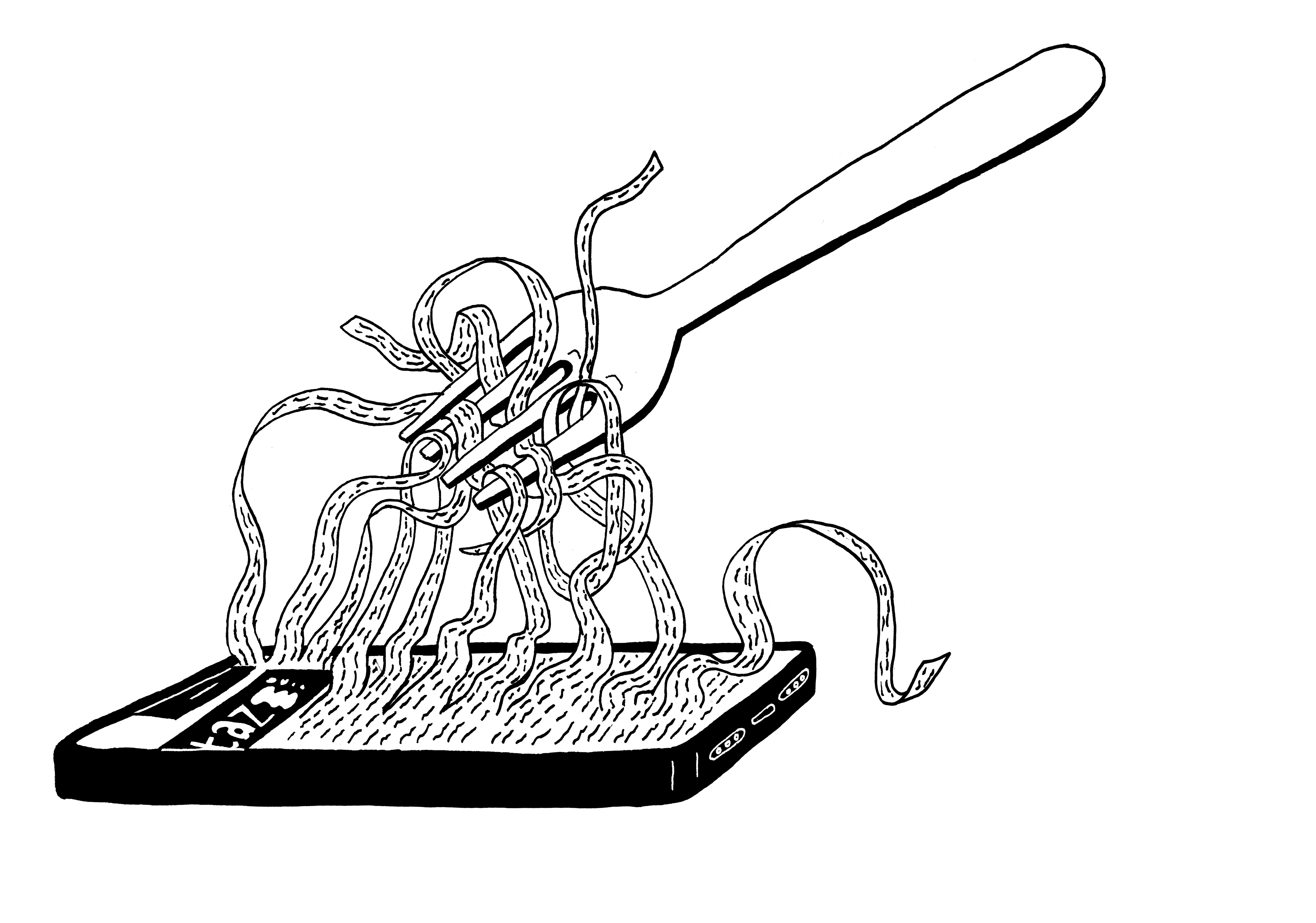

Keine einfache Lektüre: aber Edelsteine, was ihren Gehalt an Gedanken betrifft. Wenn Sie also zufällig in einen Opersänger in Australien verliebt sind oder eine aufgeweckte Theaterwissenschafterin in Alamaba beeindrucken wollen, bestellen Sie dieses Buch! Die aktuelle Ausgabe von Maske und Kothurn hat mehr Stoff zu bieten als in einen 50-Kanal-TV-Abend passt.

In seinen »Notizen zur Sammlungsgeschichte« (2002), die wohl eher Notizen zum Sammlungsbegriff sind, versucht Klaus Heinrich klarzumachen, was in unseren Museen tagein, tagaus so geschieht:

»…Just as the early gatherers found masks under leaves that started to sing to them in familiar if unknown voices (the voices of their ancestors), telling them of the past and future of their tribe, so archeological finds, those altar wings, images and environments, talk to us, quite independently of any issues of ascription, dating and interpretation (they follow on from the tale, translating it). It is the epiphanic character of the collected items in the major collections (albeit also of the very small and completely private ones) that makes them so fascinating. The items cause reality to appear anew before our very eyes. To make a finer point of it, it is not the objects, but the epiphanies that are collected. This is a process with which every collector is familiar, and it reveals two things: the collector’s need for epiphany (but where does it come from?) and the epiphanic satisfaction that the collected items grant the collector and the visitors to his collection. (We can well assume that constipation and evacuation, those feared side effects of collecting – and they were not unknown to primitive peoples as the custom of archaic potlatch shows – secretly pursued an epiphanic goal that only secondarily entailed self-purgation)…«

Das Raffinierte an Heinrichs Text ist, dass er mit der üblichen Aktion des Sammelns zugleich immer einen zweiten, scheinbar unzusammenhängenden Begriff mitdenkt: den der inneren Aktion des »Ich sammle mich«, die Spaltung ausdrückt und einen wohl auch vor Spaltung bewahren soll.

Warum also, fragt Heinrich, suchen wir die Gattungshöhle Museum auf? Seine tiefschürfende Antwort:

»… The collector’s need for epiphany leads back into his own early years as it does into those of the human species, and perhaps even further back, into our prehistory as animals. The philosopher who used the concept of aura to describe the epiphany, in particular that of the artwork, described it as something intangible – as the closeness of something distant, which, as we know, is always also the distance of closeness. However, this does not provide an exhaustive account of the collector’s need and the power of the artwork. The aura, that intimation of something, is reminiscent of an early breath, just as the mirrored image intimates the older mirror, that of the mother’s gaze, which absorbs the distraught gaze of the child, the child’s still speechless horror, and then transforms it and returns it to the child as a tolerable, expressible, comprehensible gaze that calls on the child to join the mother in processing it. Psychoanalytical experience, which has long dipped deep behind the oedipal rivalry of the sexes, offers us a key for what is sought for here, and for the rest of the child’s life, and is found again, in ever new translations of such a mirror with the power of transformation, and which not only allows us to understand the collector’s need for epiphany, but also the epiphanic power of images to banish the horror and enable us to process it. Indeed, an observation of children before they have the capacity of speech draws our attention to the fact that this search is not mere regression, but contains within itself the promise of new intellectual horizons. It is for the sake of this promise that we seek out the species caves of the museums, and it is one of the most powerful, and politically effective motifs behind the great collections being established – and yet it is also something that we must acknowledge inheres in some form in the smallest, most eccentric ones, as well. In each individual case, focusing on that promise of the new can preserve the history of collecting, which actually follows its objects to the grave, from the temptations of regression… «.

In diesem Zusammenhang erinnert der Berliner Denker an den im Mai 1997 ausgeführten Versuch, den sogenannten Habsburger Bildertausch in Wien aufzuarbeiten:

»…All major collections originally arose as projects of power and prestige, for the sake of personal salvation, for the purposes of enjoyment and education, to the greater glory of a family, a state, or a city. And such politically motivated collecting by no means reduces the epiphanic impact of the collection, as is shown by a project housed here, that explores the so-called Habsburg exchange of paintings, whereby the first-born, Viennese branch of the House of Habsburg in Vienna and the secondborn, Florentine branch exchanged paintings, as well as all the attendant circumstances and consequences. The pictorial epiphanies of the major collections that wandered back and forth between these two cities form a subterranean imaginative context which also shapes the way the large cities are perceived, or, as I put it on one occasion: Florence would be a different city without Bellini’s allegoria sacra, the dream vision it has absorbed, while Vienna would be different without the return of the apocalyptic vision of Titian’s Shepherd and Nymph, which was rejected in Florence. However pointed such claims may sound, we cannot get by without them if the history of collecting is to be accorded its due place, and not just be regarded as a form of archiving…«

Michael Hüttler (Hg.): Maske und Kothurn. Intern. Beiträge zur Theater, Film- und Medienwissenschaft, 52. Jahrgang 2006, Heft 4: Lorenzo Da Ponte, Ausgabe in engl. Sprache, 188 Seiten, Wien/ Köln/ Weimar: Böhlau Verlag 2007, ISBN 978-3-205-77617-8, EUR 23,80

© Wolfgang Koch 2008

next: DO