Warning: this is a very long post. It includes a little entry followed by a magazine article. Anyone who doesn’t have the patient can read the shorter version here.

A couple of months ago I read a news report about an attack of an Israeli teenager in the city of Laucha. The story grabbed my attention when I read about the family history of the victim: one of his grandfather was the only survivor of his family from the Holocaust, the other died in the attack of Israeli athletes during the 1972 Olympic games in Munich.

So I drove there and filed this unbelievable story for Haaretz. Then I called some local papers and offered the story for free, I just felt that it was my duty as a journalist and citizen to get the story to as many people as possible. Every paper refused my offer giving a variety of reason. In the last few days the German media is filled with the aftereffects of the story. I think that is shameful that the whole story wasn’t told (only Die Zeit sent their own reporter). It is one thing to live in sexy and vibrant Berlin, it is another to ignore what is happening in its vicinity. Here is the full and very long story of my visit to Laucha:

A few minutes later Alexander Palloch arrived to the station. Palloch, a 20-year-old native of Laucha is known as an unemployed drank who belongs to the extreme right and spends his time looking for victims for his appetite for violence. Palloch was already arrested twice in the past by local police after he distributed right wing propaganda, but no charges were pressed against him and he was released. He wasn’t very drunk yet when he arrived to the station, according to witness testimonies given to local police. When Palloch saw Shapira he yelled „Jewish pig“ and began beating Shapira in the face. The stunned Shapira protected his head and after a short struggle he managed to get away from Palloch. He turned right into Bahnhofstrasse but never noticed that Palloch restarted the hunt. after 30-40 meters Palloch got to Shapira, dropped him to the ground and started again with blows to his body.

Just a few minutes before the incident took place, Mario Traebert finished his shopping at A Plus supermarket. He got into his car, started it and made a turn into Bahnhofstrasse. As he was driving slowly

between the main train station and the local post office Traebert saw a group of kids standing on the corner and looking down the street where two other kids were struggling. Traebert turned left and saw Palloch kneeling over Shapira and astonishing him with blows. Traebert didn’t hesitate: he stopped on the right side of the road and yelled at Palloch to stop. Palloch froze for a second, enough for Shapira to evade his hits and run, Traebert turned, drove with his front wheels on the sidewalk and blocked the path of Palloch. He opened the passanger door and yelled to Shapira to jump in. Shapira obliged and Traebert put the car into reverse and raced down the street. Palloch, recovering from the shock of somebody having the courage to intervene him in his leisure activities, run after them and kicked the back door of the car as it was speeding away.The incident would have been just another number in the annual statistics of extreme right violence in this region. If it was under normal circumstances, the police could have swept it into another fight between two teenagers. Each year the police records close to 150 physical assaults by the far right in this region. The number of actual such incidents, according to social organizations working in the area, is higher by one third. Most of the victims, nearly two thirds, are German alternative youth: punks, anarchists, children who belong to the extreme left. The other third of the victims are foreigners who live there.

But Alexander Palloch scream just before he started beating Shapira, turned the incident into a different category. Now it was an anti-Semitic attack, a physical attack with a political motif. The number of anti-Semitic attacks do not exceed one incident or two a year in this region. Mostly, it seems, because there are not many Jews who live there. Palloch couldn’t find a worse victim for himself: the attack on Shapira was the third generation of German violence or violence in Germany aimed at his family. His maternal grandfather, Yoseph Lev, born to a family of Rabbis, managed to hide in the Warsaw Ghetto on the day his entire family was transferred to death in Auschwitz. His paternal grandfather, Amitzur Shapira, was one of the eleven Israeli athletes who died in the terrorist attack during the Munich Olympic Games in 1972.

Going after love

There is only one reason why a woman in her midlife will take all of her belongings, put them in a container, take her two sons (ages 13 and 7), say goodbye to her family and the house that people were willing to swear that was the most beautiful house in Oranit, and her blossoming career and leave to a foreign place, a country where she doesn’t know the language, the customs or the people. Love can lead people to behave in a very irrational way, but it’s just the disintegration of what you thought was the greatest love of your life that can cause a person to take such extreme measures.

Tzipi Lev was born in 1960 and was a flower child even before the decade defined itself as such. Her parents (her mother was prisoned for 2.5 in Baghdad because of her Zionist activities) were summoned to school every other day because Tzipi again threw chalks on the teachers or whatever the devil told her to do that day. Her nickname was „Tzipi fire“ and she was a classical sandwich child, the one who is willing to travel hundreds of kilometers in order to get one inch of attention.

At age 12, as student in junior high („I was the only boy in a girls‘ school“, she says) she found her big love: Oz Shapira, the most beautiful boy from the boys‘ school across the street. In a totality that characterize every decision and turn in her life she completely devoted herself to him. He was her first love and she thought he will be the last. Sometimes they got separated and go out with others only to prove to themselves that they belong to each other. The fact that Oz’s father, Amitzur, was one of the victims of the Munich disaster was rarely talked among them. When they visited Munich as tourists after their marriage, Oz even refused to visit the Olympic village.

Tzipi became aware of her father history only when she turned 17. Her father preached his three kids never to hate or seek revenge, and to do whatever it takes to make that what happened to his family will never repeat. Sometimes his behavior toward food–how much they should eat and how much food should be in the house just in case–was borderline obsessive and resemble the behavior of other survivors, but it was only in 1977 when an American TV crew came to interview him every day for three months that Tzipi get to grasp his childhood. „Suddenly I heard about the day he was hiding in the ghetto and watching his entire family go away“, she recalls, „about his life in the ghetto and how often luck saved him“. She heard about the day when the Gestapo stopped him with other kids and asked them to strip so they could see who was circumcised, and how they had to leave just a minute before he dropped his trousers to death. It was also the first time she heard about the Polish peasant who saved her father by hiding him for one year in a doghouse in his yard. after thirty years of keeping it to himself, Yoseph Lev was flooded with emotions. He got a heart attack and was saved only by Tzipi’s resourcefulness.

After the army Oz and Tzipi decided to move together. He was busy setting up the „Amitzur“ sports associations to carry the memory of his father. She engaged in an exchange of youth delegations and began to cultivate her love of dance. They buoght a private house in Oranit, a small house near the West Bank and in 1987 Shahak, their first son was born. in 1993 L. was born. In between, Oz decided to purchase a farm and cultivate his love for riding horses into a profession. Tzipi Became the founder of Israel’s mass gymnastics field. She ran courses and organized huge events with thousands of dancers throughout the country and abroad. Together, they lived the new Israeli dream: a single-family home, two jobs, two kids and two cars. In 1996, the alarm clock woke them up.

Tzipi continued her activities with the youth exchange program between Germany and Israel. The Israeli organizing committee used to meet once a year with their colleagues from Germany, including one member, Olaf Osteroth. Tzipi and Olaf fought all the time. he wanted to include Palestinians in these exchanges, she strongly opposed. „She is excellent in fighting and arguing“ Remembers Osteroth. Her house in Oranit was a jewel, the ideal place to host foreign delegations for Shabbat dinner, tea, and a tour to Elkana, where the guests could witness how close is the border with Palestine. When Osteroth was within hearing distance, Tzipi always told the story of how she was bombarded with stones in the neighboring Arab town Kfar Qassem when she was eight months pregnant.

In 1996 Tzipi received an official stamp for her talent as a choreographer of mass gymnastics when she was appointed chief choreographer of the Maccabiah Games. But the opening ceremony, the culmination of her career, was marred by the collapse of the bridge the delegations were marching on and the death of four Australian athletes. And then, like a domino effect, her life started to crumble. 3-years old L. got kicked on his head by one of the horses on his father’s farm. He miraculously escaped without paralysis or brain damage but will suffer from attention deficit problems for the rest of his life. Her marriage fell apart, her father died and her mother lost her will to live without him. She acceped the role of chief choreographer for the 2000 Maccabiah Games, and she was appointed to host Olaf again for Shabbat dinner. „What I did not know was that he arranged it so he will be hosted by me. And then someone took him to see my entire house while I was cooking, including my bedroom“. Olaf returned to Germany, called her and asked why there is only one pillow on the bed. Tzipi answered that she sleeps without a pillow.

Balloons over Laucha

Olaf Osteroth was born in Hamburg in 1963 and immediately after the collapse of the Wall he moved to Laucha, as the president of German youth aerial sports. He fell in love with the vineyards, fields, lakes, the quiet life of a German village, and one local woman, and settled there. There was only one strange thing about Laucha. Every April 20, Hitler’s birthday, somebody put a statue of Hitler in his window sill on the second floor of the two-story house on Obere Hauptstrasse 14. Red, black and white flag, the Reich war flag, hung from the window and everyone could have heard the voluminious Nazi music coming from inside the apartment. Olaf thought it was an individual, isolated incident. No one in Laucha seemed to care or notice. „After the unification there was no police here and anyone could do almost whatever he wanted. Just the Wild East“, recalls Osteroth.

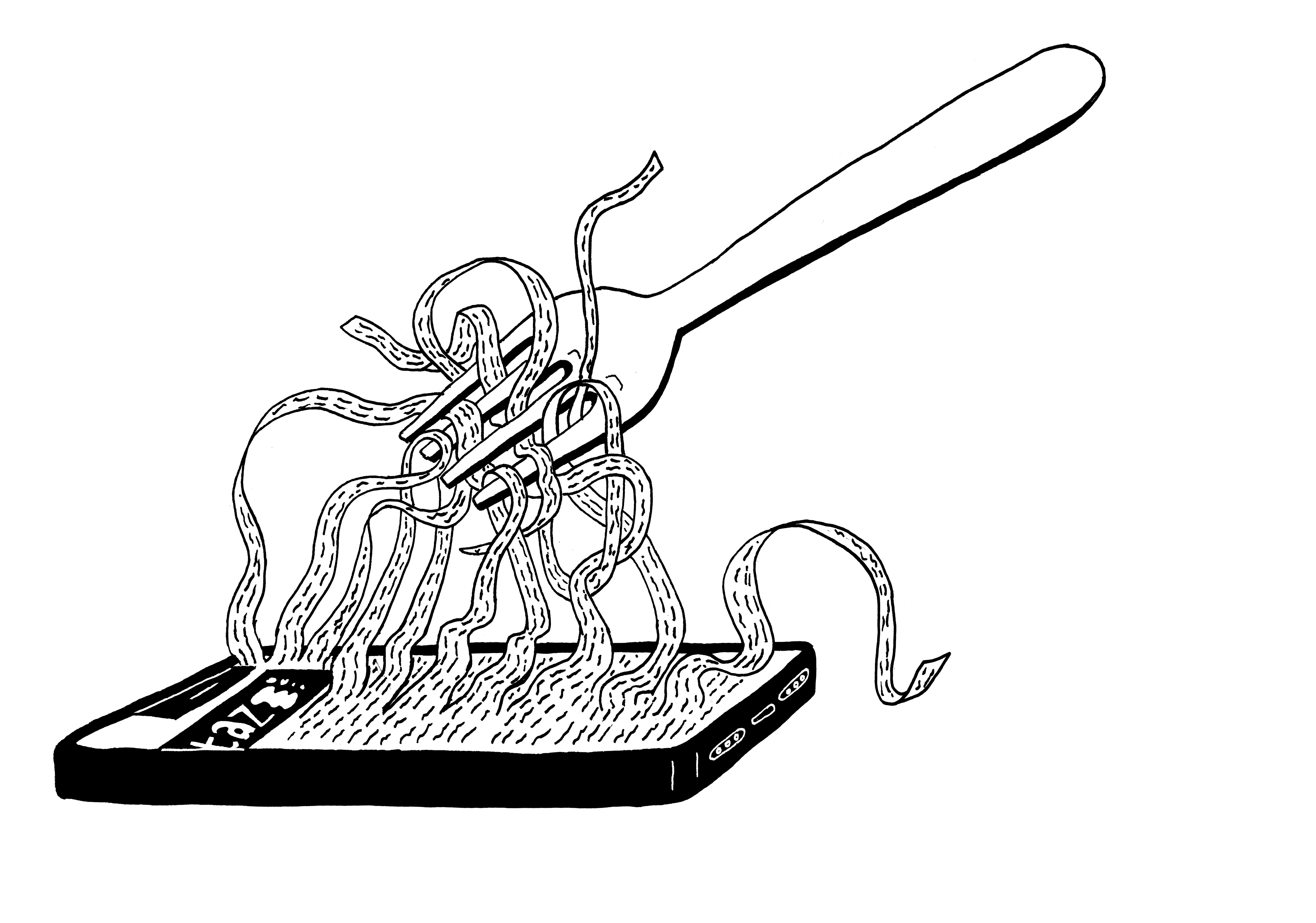

In the late 1990’s Olaf founded an air balloon company for people who want to travel with balloon or companies that wanted to advertise with the balloons. It’s a wonderful family experience: participants are involved throughout the trip, from the inflating of the balloon until its folding. It is a trip that one knows where and when it starts but no one know when and where it will end. Olaf business prospered and with his partner and the new daughter they had he was ready for life routine. But in one of his visits to Israel he takes a sidetrack from the main road. Tzipi’s fire is consuming his routine. He falls madly in love with her. He returns to Laucha and inform his partner that they can’t continue to live together, and then he makes his long distance carrier very happy.

Tzipi answers his phone calls courteously but she is waving him off gently. There is no chance she is going to fall for it. „I was in love with him,“ she says, „but there wasn’t anything logical about it“. She was at the end of a tedious and exhausting divorce. She did not want to hear about men. She wanted to travel with two feet on the ground and to know where she is going to land. He must be out of his mind, this Olaf, she says to herself, if he thinks that this 100 percent Israeli woman will leave to a foreign country. But he keeps calling and convince her to meet for a weekend in Frankfurt. And then another weekend, and another weekend, and then Tzipi discovers that this sensitive and gentle man had captured her heart. Of course he did: Olaf Osteroth gives her more attention then any sandwich girl can dream for.

In 2001, she receives a job offer from a German company in charge of the opening ceremony for the 2006 World Cup. Her family gives her its blessing, but her husband’s family opposed to her going to the „Land of the Nazis.“ Zippy decides to go for an experience. If she doesn’t like it or if her kids are not satisfied, they will go back. Olaf tells her about a Nazi in town and she thinks: one Nazi, we’ll live. She moves to Laucha.

Government-sponsored Nazi

In 2001, Battke decided that like every self-respecting football club, BSC99 should have its own flag. He chooses a black-white-red flag with the club symbol in the middle. Jana Grandy, then Laucha’s mayor and the current regional mayor, decides to boycott the club and promise not to set her foot there. Despite her efforts she can’t stop the budgeting of BSC99 or even bring on the question why the city should support (by giving the training complex for free) such a racist and ignorant club. Grandy is quiet alone in her crusade. Laucha’s resident are quite happy with the club and its coaches: they give their kids a framework, and self esteem through the winning, and for them it is more important than a controversial flag or political beliefs. It doesn’t bother no one when the club rejects an application of a teenager to join the club only because he is black.

In 2003 the club officials decided to leverage its popularity into political movement, a routine step in small villages of former East Germany. In the election the following year Battke runs on the club ticket and gets more votes than any other candidate. In 2007 Tzipi and Olaf help to bring an Israeli dance group to Laucha’s birthday celebration. Before the band performed, Battke tried to recruit players from the club’s training complex to join him in a protest march onto the town hall where the band was supposed to appear. He was unable to overcome the resistance of some of the club’s management and decided to go alone. He makde huge posters and hang them around town without a license: Israeli flag with the Star of David dripping with blood and a slogan that shouts „Israel is a murderer“ as a response to Israeli bombing in Lebanon. Local police removed the signs and returned them to Battke who immediately hanged them again. Battke was fined and the mayor decided to ban him from any informal meeting of the Town Hall. In 2009 Battke ran again for the city and regional councils. He ran independently but NPD is asking him to run on the party ticket. Only 48% of all eligible voters get to the polls. The NPD drive in words and literally, potential voters to the ballots. The NPD gets 13.5 of the general votes and gets two members to Lauch’s city council and three to the regional council. Again, Lutz Battke gets more votes than any other candidate.

Even before the last elections Saxony-Anhalt Ministry of Economy tried to suspend Battke from his job as regional chimney sweeper. Battke got suspended but appealed to a higher court that overturned the initial decision. According to the court, there is no basis for Battke’s dismissal from work. His views are an internal matter as long as he does not bring them to work and besides, NPD had not been outlawed in Germany. This is the excuse we’ve heard again and again when we visited Laucha: the NPD is legal under German law, said many parents who enroll their children to play in BSC99. Battke is an excellent coach who is leading his teams to victories and the kids definitely see him as a role model. Battke’s ten years of coaching football made him the most popular politician in the city, years of brooding over the city’s young kids and gaining the trust of their parents brought him political power. The brown seeds that Battke seeded (brown is the color associated with Nazi groups or parties) and his constant xenophobic preaching might have led to what happened on the evening of April 16, 2010.

However, Battke, who is listed seventh on the NPD ticket for next year’s elections (although he is not a member, the party again had asked him to run on its ticket), is not really a pure xenophobic. Together with the NPD’s other two members, he appears to the regional council meetings wearing a jacket. But once the meeting starts all three remove their jackets and stay with a T-shirt bearing the face of Iran’s leader Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The caption on the T-shirt claims „we love foreigners“.

Pastoral bodyguards

The day before we left, Frank the photographer and I, to Laucha, I talked on the phone with Zissi Sauermann a social worker with the Mobile Beratung fur Opfer rechtsextremer Gewalt in Sachsen-Anhalt, an organization that helps victims of right-wing attacks. The organization was founded in 2001 after a wave of attacks and is being funded until the end of this year by the Ministry of Family in the Welfare Ministry of the State. It supports the victims with psychological consulting, preparing them for the police report and investigation and tracking the police work on each case. At the end of the conversation I told Sauermann that I am traveling to Laucha. There was a long silent at the the other side and then she asked who am I going with. With a German photographer from Berlin, I answered. Sauermann asked that we hang up and that someone will call me soon. After two minutes I got a phone call from a guy called Enrico who announced to me that Laucha is not a place to visit just like that and that he will escort me during the visit. When we arrived at Laucha Enrico and another man were waiting for us in a Volvo station wagon. During the day we realized that they both are kind of trained bodyguards who volunteered to keep us safe for the visit.

Laucha is a breathtaking place. Ideal valley with squares of vineyards growing on the slopes of the hills from East and West. A visitor is welcomed at the entrance with a sign pointing out Laucha’s three females who were crowned as the Wine queen in the annual wine festival. A middle age town with narrow roads and houses sitting on the main road. There is not much place and spaces to hide here. Everyone knows what you ate last night for dinner. In the middle is the city square with the church tower overlooking it. Tzipi and Olaf live in an isolated two-family house, between the local school and BSC99 training complex. On the day we came Tzipi welcomed us with orange ribbon to her blonde hair, flip flops, black tights and long white shirt with prints of newspapers, flowers and hearts. The two-floor house mixes classical furniture with Judaica products. The walls are decorated with paintings by Tzipi, images of pastoral and ideal family life.

On the dining room table there was a laptop open on Israeli site with the news about L. Shapira attack and the many respondents who cursed Tzipi for putting her kids at risk and returning to live in the country that changed the course of their grandfathers‘ lives. Music from an Israeli radio station came from the kitchen and the newspapers basket in the toilet was filled with Israeli cross puzzles. there were three types of mint growing in the garden in the back of the house. When I asked her for her phone number, Tzipi automatically started to give me the digits of the telephone she uses on her visits to Israel. The phones kept ringing: Israeli producers eagerly asked Tzipi for an interview for the newscasts, trying to understand, just like talkbackers on the Internet, what the hell she was doing there, in Germany, and in the middle of the this nowhere place. She let the phone rang throughout our meeting. Her phone plays a Spanish song when someone calls her, Olaf’s phone (their number differ only on the final digit) plays a song by Louis Armstrong. Later, when I listened to the recording device I found a soundtrack of Louis Armstrong in Spanish, her fire in his calm). She refused to answer perhaps because she wanted to distance herself from the sensation of grandparents and grandson, or explain why she still stays here (she wanted to leave on the night of the attack, but Olaf watered her down and persuaded her that now, more than ever, they should stay and fight, carry her father’s heritage not to let it happen again. besides, she said to herself, why and how one should explain love).

Nearly an hour into the interview, at quarter to two, L. returned from school. Tzipi asked him about a hundred times what he wanted to eat while caressing his belly. He was wearing short jeans just below the knee, a white shirt with prints and socks slightly higher than his basketball sneakers.Except for a scar in the head, a souvenir of his horse accident, you could not discern any injury to the attack. But as the surgeon informed Tzipi after his three-hour surgery in 1996, no one knows what internal injuries L. will carry for the rest of his life. Jana Grandy joined us in the living room a short time later, she was wearing jeans, purple blouse and matching shoes. She was wearing a necklace designed by Tzipi Lev.

„I’m not afraid“, declared L. at the beginning of the interview. „I consider myself also as an Israeli but I can’t see myself living in Israel“. He doesn’t blame his mother and her decision to move to Germany for the attack. „I can be beaten even in Israel“, he says.“ My friends are here, my connections are here, I’ve been here from the age of seven“. Only a month after the incident, he already went out to sleep at a friend’s house, promising his mother to call her at eleven. „As a Jew,“ he said before he left, „I can not run or hide. to the contrary, I have a right to live where I want. Precisely because of what happened to my grandparents“. He is angry and don’t understand the Germans. „My generation is all the time asking not to connect them to the past, but if that’s the case then they are supposed to be much more angry than me about this incident. They can not let that happen. Unless they like to be called Nazis.“ When he left Olaf and Tzipi told me about an incident that happened to him at school a few months ago: after a TV program was shown to the students during a history lesson about the second world war, one of the students said „shit Jewish“. L. didn’t hear it but two other students informed the principle and the student was suspended for a week.

L. have minimal contacts to his father who is living in Israel. When I talked on the phone from Israel with the father, Oz Shapira, he only said that he hoped everything was okay with his son, he was worried about him and that he only wish him all the best. „Say, did you see him?“ He questioned me before we hang up. „Was he hurt or something?“ Since the incident, they did not speak.

Hitler on the line

Half an hour after we started the joint interview, Frank said he was leaving to take pictures around the town. He ticked the pastoral life, the municipal plaza, people on the street, the little swastika that someone gently drew on the back wall of the city council, the VW logo sticker with the Nazi eagle on a local Polo car’s rear bumper. He took shots of the yellow motorcycle of Lutz Battke with the sticker on its left side saying „one heart for Germany,“ from a campaign by the NPD. After 45 minutes, Frank returned to the home of Olaf and Tzipi. He dismantled the camera equipment and shook his head in disbelief. „It can not be what is happening here. It has to stop,“ he said again and again. His face was pale.

It turns out that Frank had gone to photograph a football practice ran by Battke at the training complex. Many parents stood around the field watching Battke scolding their babies with directions. Frank introduced himself to Battke who asked him to leave. Frank refused, claiming that this is a public area. Battke pulled out his old black Nokia and called. Then Battke talked with someone for a minute, in what sounded like he was barking orders on the person on the other side. Then Battke handed the phone to Frank.

On the other side of the conversation was Michael Bilstein, the vice president of the football club who is also the current mayor of Laucha. Bilstein tried to explain to Frank that he must leave but after a few minutes he realized that he had no way to enforce it. The conversation was cut off and Frank Clicked off the Nokia and got stunned. The screen saver of a municipal council member, a role model of children in Laucha, the regional chimney sweeper who the government and the court gave a monopoly to enter Tzipi’s house and inspect its ventilation systems, the screen saver of Lutz Battke’s mobile phone was a portrait of Adolf Hitler.

Brown wine

We went out to the training field. Even before we ignited the car, Enrico and his partner informed us that we are not going nowhere without them and crowded the back seat. Battke’s motorcycle stood there as it was standing when Frank left ten minutes before. There was no one on the field and in the modern and polished offices. We drove to the house of the attacker, Alexander Palloch at Naumbergerstasse 2. The only house under the Palloch name in Laucha is registered under Gisele Palloch. It is a two-storey house with large and messy yard.

We rang the bell twice. Someone came down the stairs and the two bodyguards pushed us so we stood behind them. The door opened and two men got out frowning. One, with short blond hair, pierced lip and eyebrow and a military undershirt exposing his many tattoos, asked us to leave the place and ordered Frank to stop filming. His left arm had two large tattoos and below them, a little above the elbow, two letters that looked like SS. We asked to speak with Alexander and he said that Alexander was not there. The other man opened the door and a woman handed him the phone. He went inside and we could hear him speak. the Tattooed man, which later we found out that he was Swen Palloch, Alexander’s cousin and an associate of right wing extremists with an E-mail address with the number 88 (numerical abbreviation for Heil Hitler), offered us a deal: He’ll talk if we buy him a pack of cigarettes. We offered him three if he takes us to Alexander. He went inside. We heard the three people whispering to each other. Swen Palloch came back, said he had nothing more to say, and slammed the door.

From there we went to Obere Hauptstrasse 14. We spiraled the staircase to the second floor.Dozens of pairs of shoes lay on the steps outside the door, one of them was the pair Lutz Battke used just 30 minutes before on the practice field. Someone must have driven him away from there, like a criminal leaving a crime scene. The bodyguards pushed us back and rang the bell. A woman opened the door and slammed it immediately. We knocked several times but there was no response. We went downstairs to smoke and I crossed the road and tried to talk with three pedestrians who were standing there. The two adult men refused to talk, got into their car and didn’t drive. The younger man, perhaps twenty years old, bespectacled, with short blond hair and a huge backpack on his back, agreed to talk without giving his identity. He didn’t hear about the incident where Alexander Palloch beat L. Shapira. We talked some more about young people in Laucha and what they have do there and then we went back to the attack.

He looked at me intently and answered referring to the victim: „Should he be here? and you?“. We drove back to Olaf and Tzipi and told them about the conversation I had with the young man on the main street across from Battke’s house. I described what he looked like and they started to surf the Internet and look for similar figures. It turns out I was talking to Ronnie, Lutz’s Battke’s adopted son.

On the way back from the drive in the city, we passed the club’s training complex and saw the names of club’s sponsors. One was Pleitz, a local firm that supply sanitary appliances and tools for hospitals (Shahak Shapira, Tzipi eldest son, worked there in one of his summer vacations). The next day we called the company’s office and asked to speak with Olaf Pleitz, the owner of the company. Pleitz screamed at us that this is his right to sponsor any club that he wanted, and that his company is sponsoring many local organizations and has no way to examine what happens in them, and that he doesn’t care who he decides to sponsor.

Another sponsoring company was Rotkäppchen, a local company and the biggest producer of sparkling wine in Germany. The company produces wine since the 15th century and is one of the few success stories of East German firm which not only survived, but bought its western competitors and became the leader of the German sparkling wine market (if you are flying with a German company and ask the flight attendant for sparkling wine, you will get a small bottle of Rotkäppchen). Gunter Heise, The company’s owner, still lives on Tannengartnen strasse in Laucha, three minutes ride from Tzipi and Olaf’s house and from the practice field where his firm’s sign decorates the fence. When we pulled into his house driveway, his wife was leaving the house. We asked her if it was possible talk to Herr Heise, and she said he wasn’t there and what was it about. We said we wanted to know whether he knows, and why his firm sponsors a football club that employs a known right-wing politician as one of its coaches. She took our contacts.

A day later Korenke sent an e-mail expressing regret for the incident and asking to see what the real reasons for the formation of a situation where people like Battke getting permission from parents and authorities to educate young people. She also wrote that effecting immediately Rotkäppchen had decided to cut all ties and sponsorship deals with the club.

Mayor shock

Just before we left Laucha, we took some photos of Mario Traebert on the place where the incident occurred. There was a group of teenagers on the bus stop where it all began. We spoke with one of them, Sophia Podvoriza, 15, a classmate of L. It turns out that she was at the bus stop on the night of the attack. She told us her version of what happened. „L. Sat at the bus station bench and boasted that he could get marijuana and hashish for anyone“, she said. „Alexander Palloch came to the bus stop, and asked L. not to sell drugs to his niece. They started to argue and Alexander shouted ‚drug pig‘ at L. and then hit and chased him“.

I presented her version to Tzipi who almost immediately confronted L. He denied the claim vehemently and provided us with name and telephone numbers of other people who were near the station on the night of the attack. We talked to two of them and they didn’t recall any argument taking place between Palloch and L. or hearing L. bragging about his ability to get drugs. A day later. We called the home of Alexander Palloch and a woman on the other side raised a similar argument. She also reminded us that hers is a Protestant family and therefore can not hate foreigners. She spoke to me in the first person, which is considered to be very rude in Germany. I rang the Battke who slammed down the phone on me. Then Frank the photographer called him and Battke told him, half-threatening, that they know his name, wished him a nice weekend, began to sing (Dy.. Dredy .. pretty .. pretty .. pretty .. Dy.dy. . diddle .. roar) and hung up. From conversations with social workers, prosecutors and police we found that attacking the victim and presenting him as a corrupting figure is a known and favorite tactic by the far right. Another tactic is to try to build a case that Palloch was drunk and not aware of his actions. „There’s no way he was too drunk,“ says Mario Traebert. „You can not chase someone for 40 meters if you’re so drunk. It was clear that the attacker was fully conscious of his actions.“ We later learned that Sophia was Alexander Palloch girlfriend. Last Friday she was taken from school by the police after telling other girls to testify that L. was selling drugs.

When we talked with Sophia there was also a cop standing nearby, trying unsuccessfully to look for the swastika that was painted nearby. We told him about Battke’s screen saver and the policeman claimed it is Battke’s private business and convictions and that the police can’t do nothing about it. The next day, at six-thirty in the morning, the phone rang in my apartment in Berlin, and a police investigator was on the line, informing me that the investigation was complete and I should call the police spokesman for details. The police also contacted Frank to ask if he can provide them with any images of Lutz Battke.

A day after our visit to Laucha a ceremony took place in the city municipality honoring the brave acts of Mario Traebert. Erben Rudiger, state secretary in the interior Ministry of Saxony-Anhalt, and the man who pushed to remove Battke from his job as regional chimney sweeper (members of the right track rudiger schedule and try to interfere his speeches wherever he visits) stated that the situation can’t continue as it is, And Laucha’s former mayor said that he was proud of traebert courage (Traebert got 200 Euros worth of shopping coupons and a free ride on one of Olaf’s balloons) but ashamed that a minority is turning Luacha into a brown city and that it is the leader of the city duty to wake up the residents and start to act (only 48 percent of those who were eligible came to vote in the last elections). „I think that it is hard to make a complete separation between Battke’s ideology and actions and the attacker“, Rudiger told me in a telephone interview. „After all, Battke doesn’t hang his ideology on a hanger in the dressing room when he enter the football club. His is the most dangerous example of how the NPD is trying to escape the extreme and reach the center of the society. This is their strategy and it is based on the public’s closing their eyes to what happens and becoming apathetic. Here they see him only as the coach, not as a bad person or xenophobic“.

Olaf Osteroth also spoke in this ceremony. „It can not be that the younger generation is being educated by neo-Nazi“, he said and turned to Michael Bilstein who was also present. „Alexander Palloch comes from a broken home, he escaped from school and the only guidance he had came from the football club. We can’t let NPD supporters coach and teach in this club“. Bilstein, who talked privately with Grandy and Rudiger before the ceremony, announced that in the coming days he will meet with the club’s other officials to discuss how the club should handle Battke. If nothing will happens, he promises, he will leave the club. „In 1999 We thought that the club will help to integrate people like Battke into the society“, Bilstein said in a telephone interview. „It is now 2010 and we must admit that we failed. We have succeed in sport but everyone is just talking about the Nazi team of Laucha“. This is a change of nearly one hundred and eighty degrees from what Bilstein had to say after the attack. Then he claimed that there was no evidence that Battke was connected to the attack, that the children adore him. „He works with young children and I do not believe he has bad influence on them“, he told the local media immediately after the attack. „we’ve Never heard complaints from parents about him, if there were complaints then that’s another story“. That response was consensus in Laucha toward Battke: turning an absolute blind eye, parents admired him as a lovable coach who was born and raised in Laucha. They gave him silent support by misidentifying him politically

The police investigator informed Tzipi and Olaf after the ceremony that the investigation was completed and its results were handed to the prosecution in Halle. The police questioned eight witnesses whom their testimony corresponded the original chain of events (meaning that Palloch and L. didn’t have a verbal confrontation and that Palloch did scream „Jewish pig“). The police served their recommendation for a crime of personal injury with political motives. Alexander Palloch, following his attorney’s recommendation, refused to come to a questioning, and for now he is just suspended from the club. The police also started an investigation about Battke’s screen saver.

An Israeli and a German get on a balloon

Tzipi Lev and Olaf Osteroth are not going anywhere. Sometime in the future they’ll leave, maybe even to spend their late years in Israel. In the meantime, they stay to fight. Fight for the identity of their city, against the indifference of most of Laucha’s residents, try to convince them to pour all of their shame at the polls. They will not surrender. They want Germany to stop saying that this is only a minor problem that exists only in villages in the east ravaged by high unemployment rate. If nothing changes within a year, they say, they’ll pack and leave but not before all of Germany will know what is going on in its brown corners. „There was a case, where an exchange delegation from Armenia was staying in the neighboring city“, Olaf says, „and the host family simply didn’t allow its guest to go to Laucha out of fear for his safety. It’s crazy and it can’t go on like that. The residents must unite and not let Laucha turn into a brown place“. Olaf is angry with Alexander Palloch but mostly he feels sorry for him. „East Germans are the real victims of post war Germany“, he explains. „They are the losers of the Union. I don’t believe that anyone is born a Nazi. It is only the impacts of the environment and surroundings that turn one into Nazi. I don’t even believe that Palloch understand anything about Nazism“. Osterath is less emphatic when he discusses Battke. „When I meet him, I hope that my brain will do the reaction and not my emotions. When people falls as deeply as Battke did it is impossible to save them, we can just isolate them from the public“.

„My Bird of Paradise“, that’s Olaf’s nickname for his Tzipi. his bird of paradise. He looks at her, wrapping her with love with his eyes even when she sometimes wrinkle one of his shirts to disrupt his order or when she throw a paper into the plastic garbage bin when they argue. He can explain her for the 1000th time why a person should clean his empty yogurt cup before throwing it in the garbage. His bird of paradise who brought her Israeli fire to this dead town and gave it a breath of life, that thinks 120 kilometers per hour, even though the speed limit for thinking in Laucha is only 60 Kilometers an hour.

What Tzipi lev most love is when the two of them climb, like two birds, to one of his balloons and they hover over the area. There she can think in clarity about her life and her father, marriage, and the time when her mother came to Laucha for a month during the second Gulf war and told Tzipi that this house feels like a family. She remembers how her mother begged her to come for a visit to say goodbye so the mother could die in peace and how she landed in Israel on a Friday and asked her mother to stop talking nonsense only to be awaken a day later at six in the morning with the news that her mother doesn’t wake up. She thinks about her destroyed family life and how she restored a house for herself, giving stability to her two sons. She thinks of all the youth exchanges she arranged between the teenagers from the two countries and how important it is to explain to the locals about her Jewish customs and what do they mean, because it is the only way to teach them that Jews don’t have horns and some of them even have blond hair and light eyes.

Olaf thinks of his country. About how proud he is in Germany and how it rehabilitated after the war to become a great democracy. He doesn’t want to punish these kids, thinking that they are just social victims of the Union and how East Germany really suffered the defeat of the Nazi war, because the West soon started its golden generation and was exposed to new cultures and people, and how in the East they had to go for another forty years of dictatorship. in fact, he thinks, the votes for right wing parties are just a protest vote, a calling for help. He is willing to help, but first he needs someone to make the diagnosis , stand in the city square and scream that Germany is sick again, so it can start to get its medication. „The role of my generation is not to look back in shame,“ he says, „but to ensure that there will be no closing of the eyes in the present, otherwise place after place here will become Naziland“.

Together they sail and watch the wonderful scenery below. Laucha is a Slavic name and it means swamp, referring to the swamp that was the city northern border in the past. Laucha suffered throughout history from wars and nature disaster, but in 2013 this Xenophobic place will ask UNESCO to acknowledge it as a place of cultural and historical heritage, a cynical request aiming to squeeze tourists‘ money in an area that doesn’t want strangers in it. They are sailing and watching the never-ending forests below them, the vines, the abundance of water and all this green, green, green. And no matter how hard they try, from the bird’s eye, they can’t see even one square meter of brown.

.

.