[Note: This article is about how some of the unifying foundation was set for the broad non-violent demonstrations of the people of Egypt which took place during the 18 days of January – February 2011.]

On Wednesday February 8, the Egyptian Ambassador to the United Nations, Maged A. Abdelaziz, spoke to journalists at a stakeout outside the Security Council. (1) There had been an ongoing set of questions to Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and his spokesman and to the Security Council President by journalists covering the United Nations in an effort to understand what role the UN is able to play in the struggle going on in Egypt. In response to a question about the ongoing assault at the time on journalists by police in Egypt, the Ambassador said that someone from the foreigner side was instigating the uprising.

This refrain accusing outsiders of instigating the Egyptian uprising had also been expressed by Egyptian government officials a few days earlier. What is significant about this claim is that it denies the internal process by which the Egyptian people had organized themselves over a multiyear series of struggles. These struggles included labor struggles, anti-repression demonstrations and online discussions to help to determine a set of political and economic demands uniting the different sectors of Egyptian society.

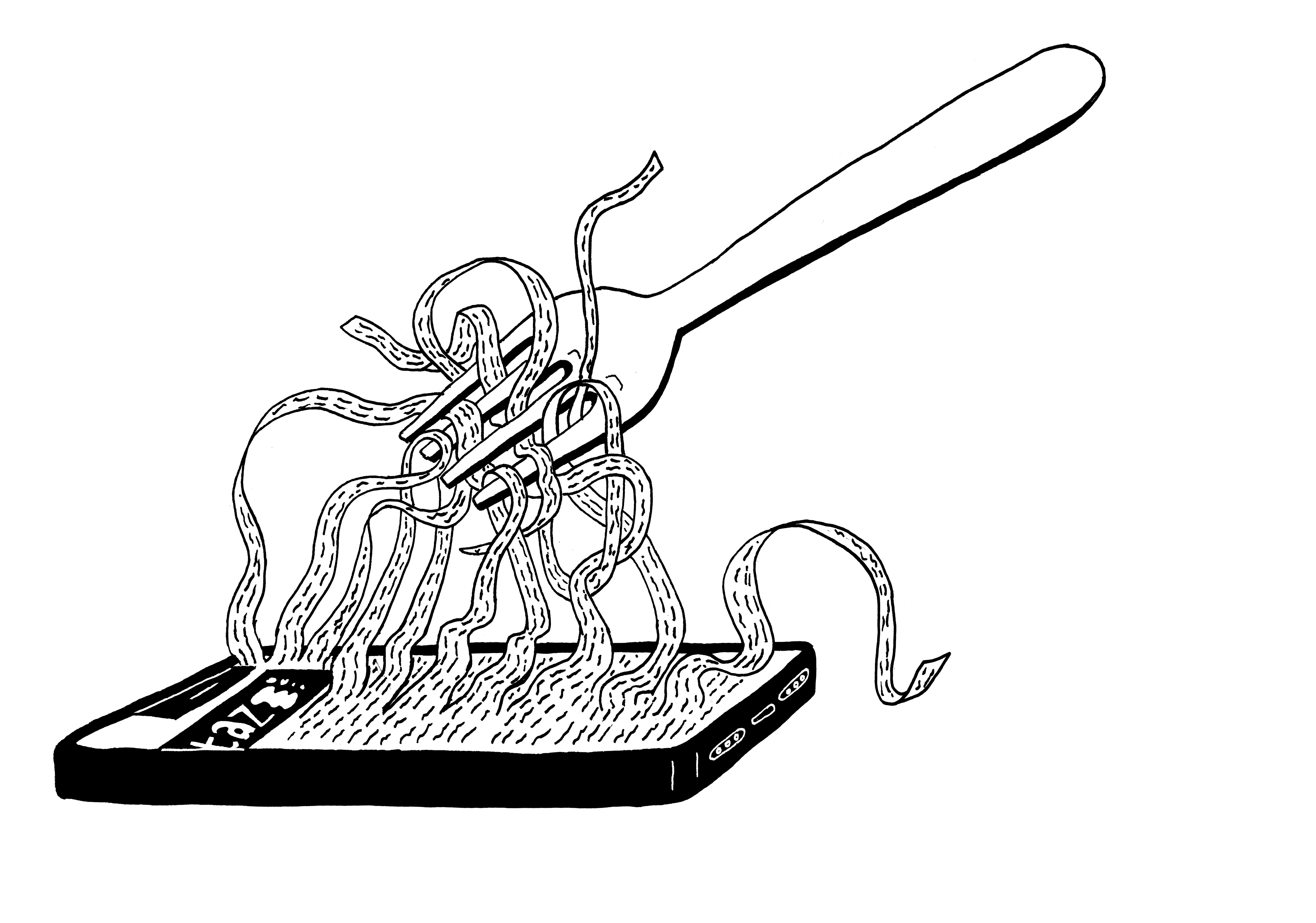

The claim of outside instigators ignores the role played by active online discussion and other forms of communication by a diversity of political actors, of citizens empowered by their access to the Internet, who had been striving for a more just and dynamic Egypt.

In the early 1990s, a university student in New York, Michael Hauben, took up to do research to explore the political power of the developing networks. Through his research he discovered that a new form of citizenship was being born online. (2)

In response to a set of questions Hauben sent out to people with Net access in the early 1990s, he received descriptions of how people were exploring how to use the Net to solve the many social and political problems of our times. He called these users who were active citizens exploring how the Net could help to make a better world ’netizens‘ (Net + Citizen=Netizen). For Hauben, not all users were netizens. Instead he reserved the use of this term to describe those users who empowered by the Net, were exploring how to contribute to a better world.

Many of the characteristics that Hauben discovered among netizens in the early 1990s are also the characteristics of netizens who have been part of the struggle to change Egypt.

Describing some of how the process of mobilization developed, Charles Hirschkind, in his article, „From the Blogosphere to the Street: The Role of Social Media in the Egyptian Uprising“ writes:

„The seeds of this spectacular mobilization had been sown from across the political spectrum.“ (3)

Hirschkind describes how a political alliance grew up between the secular leftist organizations and groups with Islamic ties (particularly the Muslim Brotherhood), working together to defend victims of state torture.

Another example of an organization working across the political spectrum in Egypt was the Kifaya movement, a coalition of those with diverse political leanings united in their demand that Egyptian President Mubarak step down and that his son Gamal not succeed him.

With the emergence of this movement in 2004-2005, bloggers became a significant part of the protest activities, reporting on the protests and discussing them online. One blogger, Wael Abbas is mentioned for distributing a video clip of a man being physically abused by the police in Cairo. This video and other forms of online reporting helped to build a movement in Egypt against police abuse.

Another contribution to the current protests was from the many labor struggles in recent years. Strikes helped to spread the sense of the importance of struggle in Egypt. Bloggers, Facebook groups, and others online took part in the discussion of grievances and in spreading the information about mobilizations.

April 6, 2008 was an important example of the power of the alliance of online netizens and workers working together to challenge the abusive practices of the Mubarak government.

Hirschkind describes how online discussion and communication have helped to transform diverse political ideas into a common set of political objectives. „They have pioneered,“ he writes, „forms of political critique and interaction that can mediate and encompass the heterogeneity of religious and social commitments that constitute Egypt’s contemporary political terrain.“

It is this evolving communication among Egyptian netizens, not foreign instigation, that helped to provide the platform for a movement which was able to embrace a broad spectrum of Egyptian citizens. Describing the movement that developed, Nubar Hovsepian, in his article „The Arab Pro-Democracy Movement: Struggles to Redefine Citizenship“ writes, „Organizationally it is more like a network than our outmoded top down structures.“ (4)

„This is a revolution,“ he explains, „in the making sparked by youth who are determined to alter the dominant paradigm of politics and power that precludes the central idea which undergrids democracy — citizenship under a social contract.“

Hovsepian argues that a new relationship between the Egyptian government and the citizens is at the heart of the movement. „Simply put,“ he explains, „Arab youth are leading a profound revolt whose central objective is the transformation of former ’subjects‘ into ‚citizens‘ with agency and voice to make demands of their rulers. The rulers are expected to be servants of their citizens — nothing less is acceptable.“

Mohammed Bamyeh in his article, „The Egyptian Revolution: First Impressions from the Field [Updated]“ describes the 18 days of the Egyptian uprising as the „dawn of a new civic order.“ (5) He points to many of the grassroots forms that developed during the days of the uprising, one of which was a mass „civic character as a conscious ethical contrast to the state’s barbarism.“

He describes the transformation of people’s sense of themselves and of their capability as an integral part of the process of the movement. „Like in the Tunisian Revolution,“ Bamyeh writes, „in Egypt the rebellion erupted as a sort of a collective world earthquake — where the central demands were very basic, and clustered around the respect for the citizen, dignity, and the natural right to participate in the making of the system that ruled over the person.“ This goal, Bamyeh explains, was expressed as well by „even Muslim Brotherhood participants (who) chanted at some point with everyone else for a ‚civic‘ (madaniyya) state — explicitly distinguished from two other possible alternatives: religious (diniyya) or military (askariyya) state.“

Describing the significance of these developments, Hovsepian regards the Egyptian events as the Arab equivalent of the French Revolution.

In a paper I presented in Paris at Sorbonne III this past summer, titled „Watchdogging to Challenge the Abuse of Power: Netizenship in the 21st Century“, I proposed that the important achievement of the French Revolution was the conceptual transformation of the former subjects into the citizens to be regarded as the sovereign of the State.(6) „It was the citizens who were to possess the power of the nation….It is among the citizens that the discussion and decisions to determine the progress of the nation belongs.“ This goal or vision has been considered only as an ideal for over 200 years, as citizens have lacked the capability to exert their supervision over the government or corporate officials who have grabbed the power of the state.

The Egyptian revolution has had its groundwork set by the Egyptian netizens and it is this foundation that provides a strength to meet the many trials to be faced in the coming days.

Hence it is not foreign instigators who are responsible for seeding the soil of the mighty movement that removed Mubarak from power. Instead it is a resurgence of the ideals and demands of citizens which fueled the French Revolution, but which are now strengthened by the actions and deeds of the netizens.

Notes

1. Stakeout at Security Council, Maged A. Abdelaziz to the press on February 8, 2011.

2. Michael Hauben, „The Net and the Netizens“, in „On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet“, IEEE Computer Society Press,

http://www.columbia.edu/~hauben/netbook/

3. Charles Hirschkind, „From the Blogosphere to the Street:The Role of Social Media in the Egyptian Uprising,“Jadaliyya, February 9, 2011.

4. Nubar Hovsepian, „The Arab Pro-Democracy Movement:Struggles to Redefine Citizenship“, Jadaliyya, February 9, 2011.

5. Mohammed Bamyeh, „The Egyptian Revolution: First Impressions from the Field [Updated]“, February 11, 2011.

6. Ronda Hauben,“Watchdogging to Challenge the Abuse of Power: Netizenship in the 21st Century,“Paper presented on July 13, 2010 at Sorbonne III, Paris, France