Last Week I wrote here a brief a brief account of my encounter with Samuel Kunz who, according to prosecution, was involved in the murder of 434,000 Jews in Belzec and killed ten of them on his own initiative. I contacted a local paper and told them that I want to offer them the story. The paper answered me that they can’t print the story, partially because I mention the name and address of Kunz.

So I have decided to run the entire story here. I really don’t care. I think that if someone will come to question me I will have the correct answer: it took Germany 65 years to find someone who helped in the murdering of thousands of people, but it took them two minutes to find someone who exposed his real name and address. So here it is, sue me:

Hermann Heck was certain his search for the perfect house had finally ended five weeks ago. After he ruled out a number of possibilities for various reasons, the real estate agent called to say he must see a gorgeous place in Oberbachem, a village belonging to the municipal council of Wachtberg, 15 kilometers south of Bonn.

Heck, a private investigator, has in recent years been looking into suspicions of alleged corruption in the German telecommunications giant Telecom. When the agent called, he lost no time: For the past year he had been looking for a new home for his partner and his 16-year-old stepdaughter, a place from which they could restart their lives, a place of repose for him.

He got into his car, negotiated the dozens of stoplights, drove through the tunnel and on to the B9 expressway, which leads out of Bonn, via the neighborhoods into which Germany spits its refugees, and into endless green spaces. The slow drive along the winding road allowed Heck to notice the ripe apples, pears and cherries that dangled from the trees by the roadside. Following a descent into a valley, after one last bend to the right, he saw the agent’s car parked next to the first house he encountered in the village, at 21 Liessemer Kirschweg.

He saw the farm across the way where horses cantered and noticed the cows that lolled lazily on the hill above the house. His search, he knew, had come to an end.

That same day he met with the owners, an elderly retired couple who lived with their son in the adjacent house, at No. 19. A rental agreement was drawn up within a few days. On the wooden door of her room, Heck’s stepdaughter put up a poster of Kurt Cobain shrouded in cigarette smoke. His partner arranged the house as she wanted, though with one condition imposed by Heck, which he has always insisted on: no carpets.

The family began to adjust to life in the village. On the way to and from work, Heck waved to his neighbor-landlord, amazed by the fact that the stooped man of 89 was still able to work such long hours in his garden and store logs for the winter. But three weeks ago, the new routine of Heck’s life was abruptly disturbed. Journalists and television cameramen swirled around the house and the police were summoned to maintain the public order.

Heck was certain that the long arm of Telecom had found him and was accusing him of some nefarious deed. But he soon discovered that the truth was far more grave: According to the German prosecution, his neighbor-landlord was a monster named Samuel Kunz, who had participated in the murder of 434,000 people, 10 of whom, the authorities allege, were killed personally by Kunz in the Belzec death camp, where he was a guard from January 1942 until July 1943.

Opting for collaboration

Samuel Kunz was born in 1921 in Russia, in a village on the Volga River. In World War II he was a soldier in the Red Army and was captured by the Wehrmacht. The Nazis gave him two options: incarceration in the POW camp at Chelm, or collaboration. After a few days in Chelm, where he saw the bodies of dozens of fellow prisoner being dragged out of the camp, Kunz volunteered to collaborate.

He was sent to the S.S. training camp at Trawniki, along with some 5,000 other POWs (among them John Demjanjuk). The trainees were subsequently assigned three missions: emptying the ghettos of their Jewish inmates, overseeing forced laborers or serving in death camps. Kunz became a guard in the Belzec death camp in occupied Poland.

He rose rapidly through the ranks and was involved in rousting Jews from the trains, pushing them into the gas chambers and evacuating the bodies to mass graves. His zealousness gained him an appointment as commander of other guards, a position that carried a higher salary and a significant improvement in food rations. But according to the indictment, Kunz, who did not deny that he was in Belzec, was no ordinary collaborator: In May 1943 he allegedly shot dead two Jews who tried to escape from the train. A month later, while seeing a guard shoot and wound eight Jews, he apparently grabbed the guard’s pistol and shot and killed the eight as they lay on the ground.

At the end of 1943 after nearly all the 1.8 million Jews who had lived in the region had been murdered the camp at Belzec was shut down. Kunz was transferred to Flossenburg, a concentration camp in Bavaria, where he first met the guard John Demjanjuk. He was captured by the Americans and, beginning in the 1960s, testified in the trials of Nazi war criminals.

„We knew that Jews were being killed and we knew they were being burned,“ he stated at one trial. „We could smell it every day.“

Finally, he moved to Bonn, received German citizenship and worked for the government as a carpenter in the Ministry of Construction until his retirement. Like many civil servants in the German government after the war which was based in Bonn until the move to Berlin in the mid-1990s Kunz saved his money until he could move to a leafy suburb, invest in real estate and disappear into the banality of assimilation. Time was on his side and work in his garden as a pensioner in Oberbachem was far removed from Belzec.

Belzec ‚laboratory‘

Toward the end of October 1941, the Germans had launched Operation Reinhard, which effectively began the implementation of the „Final Solution.“ In contrast to the camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau, which functioned also as labor camps, the new facilities Sobibor, Treblinka and Belzec were intended for the mass murder of Jews and Roma.

Belzec, the first to be opened, was a „laboratory,“ the model upon which the other camps were built and operated. The choice of its site embodied a logistical rationale: The Lublin district, in which the camp lay, was close to the Jewish population concentrations in Poland and Galicia, and the infrastructure for transporting them from Lvov, Krakow and Lublin was already in place.

The camp commandant was Christian Wirth, a colonel in the S.S. who had gained valuable experience in mass murder as one of those in charge of Aktion (Operation) T-4, in which 70,000 Germans who suffered from mental or physical disabilities were murdered by lethal injection. The first killing method at Belzec was to load Jews onto trucks whose exhaust fumes led into the sealed cabin into which the inmates were crammed.

But Wirth wanted something more efficient: He built gas chambers, placed flower pots in them and had a huge Star of David painted on the roof of the building. He received the thousands of people transported to the camp every day in packed train cars with a fiery speech, on the ramp. Invariably, some of the Jews who thought Belzec would be an improvement on life in the ghetto cheered him.

Wirth sent the inmates to be disinfected, and men and women were separated. They disrobed and handed their belongings to the guards; the women’s hair was shaved and everyone was sent to the „showers.“ Unlike other camps, hardly any witnesses emerged alive from Belzec; even those who survived until the camp’s closure were afterward put to death in Sobibor. One of the few testimonies about what went on in the camp came from Kurt Gerstein, a German chemical engineer who joined the Waffen S.S. as head of the technical department involved in disinfection. Already during the war Gerstein secretly made available information about the camp, hoping to arouse the international community to take action, but no one lifted a finger.

Excerpts from Gerstein’s testimony: „The guards pushed the Jews into the showers and reminded them before they entered to breathe deeply to ensure that the disinfection would be effective … Eight-hundred people were crammed into a room of 93 square meters. Then Sergeant Hackenholt would start his Opel truck and the exhaust fumes were carried in pipes into the gas chambers … Generally all the inmates were dead within half an hour … You could know who the families were because they held hands and there was nowhere for them to fall … Infants still lay on their mother’s breast … Then the guards would enter and kill anyone who had survived, and Jewish inmates evacuated the dead to a mass grave not before looking for gold in the mouths of the dead.“

Wirth even dubbed the structure the „Hackenholt Foundation.“ In the 15 months of its operation, 434,500 people were murdered there.

Third on the list

Samuel Kunz could have died peacefully at a ripe old age in a fine house, surrounded by a blossoming garden in a village nestled in a valley by the Rhine. Indeed,

had he already died, he would have pulled off the biggest success of his life: selecting three years from his twenties and pressing the „delete“ button. But in his case things took a different course. Among the thousands of documents transferred by the American authorities to Germany in connection with the extradition of John Demjanjuk were papers about one of the potential witnesses in the trial, a German citizen by the name of Samuel Kunz.

The German prosecutors who read the documents decided that Kunz deserved an indictment of his own. John Demjanjuk, Jr. also fanned the flames when he complained that the Germans were dragging a Ukrainian citizen his father across the Atlantic but were not bringing their own citizens to trial, even when clear evidence against them existed. Germany, he declared, was trying to purge itself of cases of mass murder.

Kunz denies the charge of having murdered 10 Jews, but the German prosecution maintains it has clear proof of his actions, backed up by testimonies from postwar trials held in the Soviet Union.

Thus, instead of dying peacefully in old age, Kunz, who is half deaf and has a heart pacer, opened the door to the police officers who scoured his home in search of evidence about his past. He and his wife complained in an interview to a local radio station that someone had sprayed the word „Murderer“ on the wall of their home.

Kunz appears in third place on the annual list of most wanted Nazis drawn up by the Jerusalem office of the Simon Wiesenthal Center. No. 1 is Dr. Sandor Kepiro, a Hungarian officer accused of murdering 1,200 civilians in Novi Sad, Serbia, who lives in Budapest opposite a synagogue; No. 2 Milivoj Asner, the chief of the Slovenska Pozega police in Croatia, who played a key role in the persecution, deportation and subsequent deaths of thousands of Jews, Roma and Serbs, but whom the Austrian authorities refuse to extradite to Croatia for an assortment of reasons.

One wonders what induced the German authorities in contrast to their counterparts in Austria and Hungary, who are doing nothing to bring senior Nazis to trial to take action against a minor figure like Kunz after so many years. The official reasons include the advent of a new generation of prosecutors, who have decided that time is against them and are now trying to put every surviving suspect on trial, from senior officers to junior guards, as well as a new approach that murder is murder and that even a foreign national who worked in the service of the Germans is indictable.

But to find the real reason we must turn to the annual report of the Jerusalem branch of the Wiesenthal Center and its author, Dr. Efraim Zuroff.

‚Failing grade‘

Born in New York in 1948, Zuroff immigrated to Israel in 1970. In 1978 he went to Los Angeles for two years to collect material for his doctoral thesis on the response of Orthodox Jewry in the United States to the Holocaust and was appointed academic director of the Los Angeles-based Wiesenthal Center.

Shortly before his scheduled return to Israel, he received a job offer from the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations (which tracks and investigates people who violated international law or participated in crimes against humanity). The original two-month position stretched into six years, during most of which Zuroff was based in Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, where he collected material and interviewed witnesses about Nazi criminals, most of them from Eastern Europe, who were then indicted by the U.S. authorities.

In 1986, Zuroff realized he was sitting on an archival gold mine. The database of the International Red Cross that is used for identifying and locating people who disappeared during World War II is housed in Yad Vashem. Its collection of 16 million entries allowed Zuroff to see where almost every East European refugee had gone. He cross-checked names with names of Nazis he read about in the archives. (They had not bothered to change their names, as they didn’t think the authorities would hunt them down.)

Zuroff decided his work needed to go beyond the boundaries of the American prosecution. He contacted the Wiesenthal Center and suggested that a database with information about all the Nazis in the world be established, which would inform authorities from other English-speaking countries (Canada, Australia, United Kingdom) about the presence of such criminals on their soil.

The Wiesenthal Center agreed and on September 1, 1986 Zuroff set to work. On October 1, he submitted to the government of Australia a list of 40 Nazi war criminals living in that country.

In the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Zuroff focused his attention on the countries of the former communist bloc. But a change of approach in the Wiesenthal Center led him to reorder his priorities.

„Although we are named for Simon Wiesenthal, we do not have a formal tie with the center,“ Zuroff says today. „It’s an organization that started out as an educational and commemorative center, and then became a political organization that fights anti-Semitism and efforts to delegitimize Israel. Nazi hunting was lowered to a secondary priority.“

Thus it seems that Zuroff remains one of the last Nazi hunters today and is certainly foremost among them. His annual report, which is published on Holocaust Memorial Day, contains a list of the 10 most wanted Nazis and also grades countries in terms of their efforts in persecuting Nazis and holding full-scale trials of them. (The reports, first published in 2002, are entitled „Operation Last Chance.“)

In 2007, Germany received a „failing grade“ for the first time since the reports were drawn up.

There is no way to prove this, but it seems the Germans took offense at their low score. That same year the country’s authorities began to implement a proactive approach of prosecuting everyone who was an accomplice to murder (thereby eliminating the popular defense argument, „I was just following orders“), even foreign nationals.

For example, until 2007, the chief prosecutor for Nazi affairs in the Dortmund public prosecutor’s office, Ulrich Maass, was an ongoing failure, according to Zuroff, in regard to bringing Nazis to justice, but afterward he displayed much zeal in putting Nazi war criminals on trial. His successor, Andreas Brendel, launched an investigation that catapulted Kunz to third place on Zuroff’s most-wanted list of 2010.

The report also awarded a grade of A (the highest one) to two countries: the United States and Germany.

The criteria by which he draws up the most-wanted list, Zuroff explains, are determined by the command rank of the individual, the scale of the murder in general and whether he took part in murder specifically. He also mentions the issue of the assimilation of Nazi criminals into the surrounding society and their ability to begin a new life.

„First of all, there are the charges brought by the country they are living in,“ he says. „There are countries such as Austria which, incredibly, have not brought Nazi

criminals to justice for the past 30 years. But even in Germany, where the political will exists, and where Nazis are tried in criminal rather than civil courts, we have not seen the emergence of a highly motivated official determined to conduct a crusade against the Nazis and in pursuit of justice. It’s true that Wiesenthal was held in far higher regard in Germany than in Austria, but I find it amazing that no German Wiesenthal has arisen.

„From the personal, individual point of view,“ Zuroff continues, „it must be remembered that 99.9 percent of those who murdered Jews did not possess a saliently criminal or psychotic personality. Very few committed suicide or became drug addicts, and only a handful ran afoul of the law. These are people who grew up with an anti-Semitic heritage and came from places which were not known for upholding human rights. The Germans and the Austrians created historical and geopolitical circumstances for them in which they received bonuses for murdering Jews and were punished for rescuing them. In later years these people assimilate into the society and the neighbors don’t ask questions, because who wants to draw a link between that horrific tragedy, the embodiment of absolute evil, and his nice neighbor?

„The hardest part of my job is to stand before the members of the family and inform then that the father is a monster, while they try to persuade me that he is

not a murderer and that no one ever heard him even make an anti-Semitic remark. That is probably true. He was apparently a murder in certain extenuating circumstances, but he is still a murderer.

„I also don’t think they live their past. Like the [Jewish] survivors with all due respect, of course, to the huge differences these people wanted only to look forward,

because that was the only way to survive, and why they moved to places with a different culture and language. In the past 20 years the Holocaust has entered popular consciousness and culture, yet no Nazi criminal has come forward to say, ‚I am sorry. I did what I did when I was young or because I truly thought the Jews constituted a threat.‘ I have bee n dealing with the Holocaust for 40 years, but have never heard a Nazi criminal express contrition. People without a conscience live longer.“

Zuroff wants Kunz to rot in prison, in a small cell where he will have enough time to think about all he did. He does not accept the view that a Nazi criminal’s age should be taken into account in deciding whether to prosecute („If an 80-year-old serial killer is caught in Germany, won’t they prosecute him?“). The passage of time, he says, does not reduce guilt, and old age does not mitigate murder. He feels a commitment to the Jewish, Roma and homosexual victims and he wants to send a message that in the pursuit of Nazi murderers the wheels of justice can grind very slowly indeed.

What will he do in another 15 years, when Nazi criminals will no longer be alive? Zuroff laughs. A few months ago he published „Operation Last Chance: One Man’s Quest to Bring Nazi Criminals to Justice“ a sort of summary of his efforts to date. (The book was published in English, French, Polish and Serbian, but to date no Israeli publisher has decided that it’s worth translating into Hebrew.)

„A great deal of work remains,“ Zuroff explains. „All the countries that are not pursuing Nazis because they do not want to draw attention to the activity of their nationals in the Nazi period are now trying to link Nazi crimes to the crimes of the communist regime. That endangers the legacy of the Holocaust and distorts its narrative. A case in point is Lithuania, where ordinary folk and intellectuals killed 212,000 of the 220,000 Jews who lived there. There is still much work to be done.“

People in the street

After I told Hermann Heck who his landlord and neighbor was, I took a stroll through the pastoral village of Oberbachem. Detached homes, swings in the yards,

Japanese cars. A picture postcard of a bored middle-class setting with a church and a cemetery in the center.

I asked about Kunz in the drugstore, post office, bank, gardening shop. Media consumption here is mostly confined to reading the local news in the paper („13-year-old Juergen reaches the finals of the kite flying competition“), but no one knew a thing about him. When I told them what Kunz was accused of, they reacted with mild shock and turned to the next customer.

Rita, the pharmacist, told me that what should really be investigated is the modern history of the German people and why they had not spat out their Kunzes 15 or 30 years ago, when the problem of advanced age did not yet exist. The salesman in the gardening shop said there were better things to do than persecute 90-year-old people. He added that Kunz had always been a model customer: „I wish everyone were like him,“ he said. Kunz cries every night, suggested the owner of the laundry. That is his punishment to live with the secret, to hide for a lifetime, to make sure that no one knows who you really are. It’s part of the new Germany, forgiving offspring of unmerciful fathers.

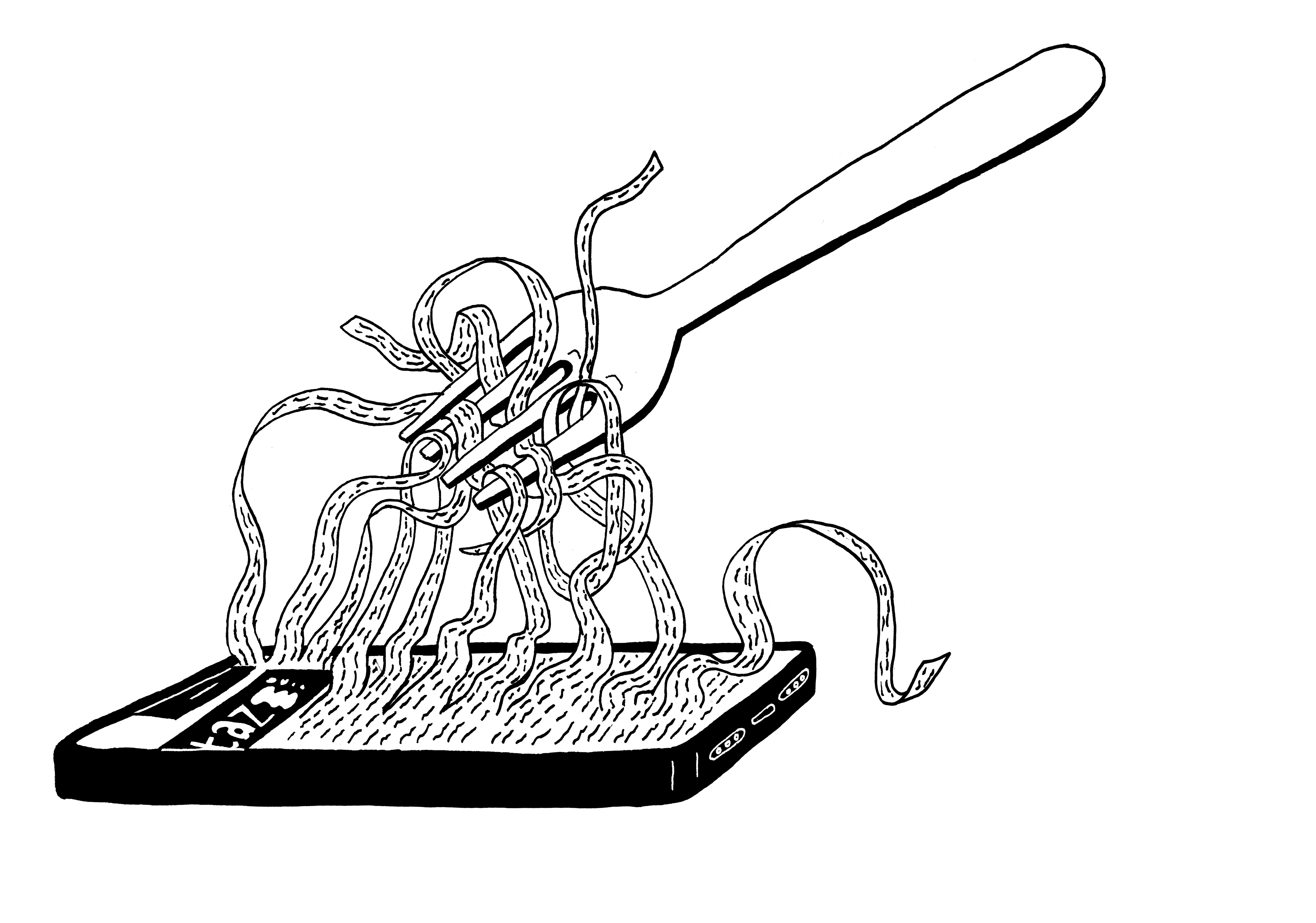

Returning to Heck’s home, I found him sitting at the kitchen table with his wife, both of them chain smoking. On his iPhone he read the latest news about their neighbor; on a laptop, his wife found other information.

„My daughter is very active against the Nazis,“ she told me. „I don’t know what I will tell her when she gets back from her vacation.“ Both of them punctuated their remarks with expressions of shock and dismay: „Unbelievable.“ „It can’t be.“ The problem with Germans, Hermann Heck said, is that we like to sweep everything under the rug.

I left the house and turned right. No. 19 seemed perfectly normal. A white fence, two garbage bins, a box for mail and another for the newspaper, some steps, a path and then another five steps leading up to a two-story house with a tiled roof in the shape of a pyramid, from which the second-floor rooms jut out. The name Kunz appears on the doorbell.

The garden was immaculate. Flowers in a panoply of colors which invite dozens of bees to hover around them, herbs and bushes, all in exemplary order, trimmed to the last centimeter. Decorative white curtains covered large windows, on whose sills flower boxes were perched. At one point a curtain on the second floor was opened and Samuel Kunz’s son motioned me to leave. I gestured to him to come down, but he gave me the finger and disappeared.

Suddenly I saw an old couple walking toward me along the street. She walked erect and slightly ahead of him, in a long, light wool beige jacket, a blue skirt and square sunglasses. He walked behind her, stooped, aided by a cane and wearing black pants and a gray jacket over a blue-and-red checked shirt buttoned to the top.

Can I talk to you, I asked. There is nothing to talk about, the woman said assertively and pulled Kunz’s arm. They went on walking. I turned around and said, „Wissen Sie, Ich bin Juedisch“.

Kunz stopped, turned around and gave me a long look, until his wife pulled him again and led him up the stairs toward home.