Merve: Would you like to briefly talk about the history of LGBTQI2+ movement in Turkey?

Üzüm: From a political point of view, I of course recognize the movement as a liberation movement, so I think it started simultaneously at each and every geography. It started in Turkey the same way it started in the world. I don’t think there have been several uprisings, rebellions and liberations in different parts of the world which then spread to various regions and Turkey is one of them. I think the beginning of the LGBTI+ movement in Turkey is overlapping with Transgender movement.

Of course, there are differences among the LGBTI+ movements in different contexts. But I think the recognition of identities have to do with industrial revolution. When compared from a legal recognition, some countries may seem more progressive in terms of recognizing different identities. There is no such legal recognition but a continuously growing, lively queer movement in Turkey. I am trying to analyze the situation in a deeper way. I mean, there is not one linear progression for LGBTI+ movement. We experience problems in developed countries as well. Of course, we have demands like legal recognition and equal citizenship in order to claim our freedom.

Today the governments still fail in recognizing us but at least NGOs gained some awareness about us. For example, today people can stand up to hate crimes against transgenders. The prejudices are changing. People can now accuse the murderers.

Deniz: From the identity perspective, I agree with Üzüm. There has always been LGBTI+ in Turkey like they have been in other parts of the world.

The political LGBTI+ movement in Turkey though begins in 70s. İbrahim Eren initiates gatherings called “Meadow Wednesdays”. In the 80s, the performance ban against trans woman artist Bülent Ersoy and her struggle brings visibility to the movement. In 87, all the transgender people are collected and sent into exile in Eskişehir and for the first time in the history of Turkey, a statement on “Transgender Human Rights” is given there. With the support of the Human Rights Association, the hunger strike begins in Taksim. In 1993, there is a Pride Parade attempt which it is not allowed. Meanwhile, the Green Party is founded under the leadership of İbrahim Önder, and called as “the homosexuals’ party“, so a defamation process starts. In 1999, Demet Demir runs for the local elections and this marks the first political candidacy of a Transwoman. Shortly after Kaos GL magazine starts its journey. In 2001, Kaos GL volunteers go to the May 1 arena for the first time. In 2003, the first Pride Parade takes place.

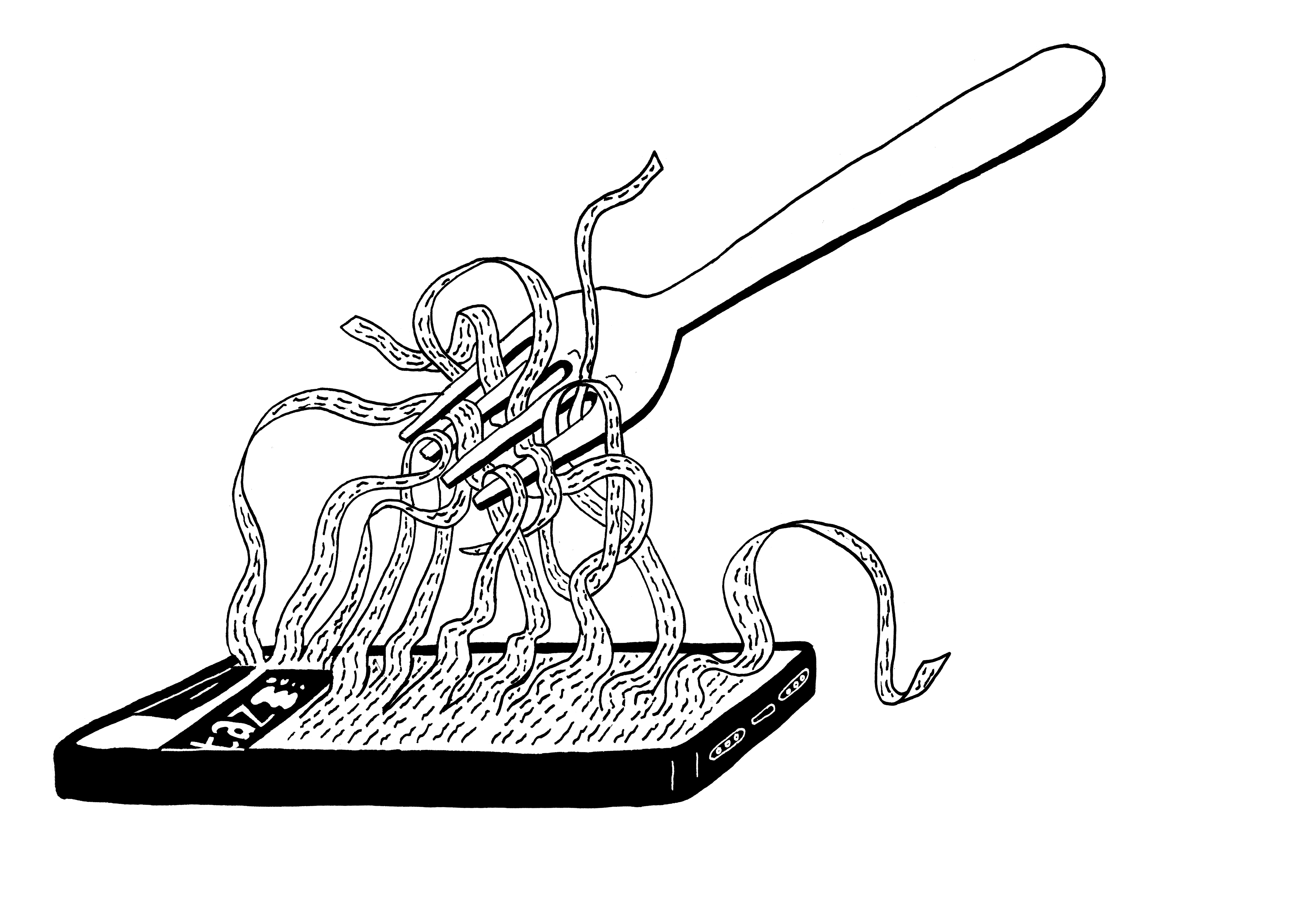

I personally become aware with the broadcasting of Ülker street events on TV. The depictions of the tortures the people are exposed: being beaten with hoses, being put in sacks together with cats so the cats can hurt them. Seeing these tortures against transgenders made me aware. I was already a political person but in political organizations these issues would not be thematized and simply ignored. The people who experienced torture at Ülker street later discussed with other guests at Savaş Ay’s TV Program “A Takımı”. I was very little than but I started questioning.

Merve: Both of you are beloved figures of Istanbul’s and Turkey’s queer community and music scene. You do a lot of work for LGBTQI2+ community’s visibility, stand against racism, misogyny and animal abuse and engage yourself for other equity and equality struggles. Would you like to talk about your queer and trans activist identity a little bit?

Üzüm: I define myself not as an activist but as a queer trans feminist. I perceive activism as a duty and think one should spare really time for it. The things I do, I don’t do for the sake of activism.

We didn’t become queer and than made our surrounding queer. To me, queer is a living organism. It is a political attitude, a reflex against the Zeitgesit. Of course, there is an identity side of it but how Deniz or you or I express ourselves as people who exist on the same frequency and the way how we claim our existence is Queer.

I come from a crowded working-class and marginalized family. I think the cultures we are born into are also effective on particular issues. As a transwoman, I cannot help but be sensitive for other discrimination issues you mentioned.

Merve: So you mean, the course of life itself is queer, right?

Üzüm: The life itself, the fluidity itself is queer. There is a resistance state. We are not just the subjects of queer experience but we also try to live here. While we are living, we try to interact and coexist with those who are not queer.

Deniz: We are people who think and put their thoughts into actions. Wherever we are, we do this. At school, at home, at work we have a presence. To survive and exist in this society as queer and trans individuals is on its own activism. We are not politically organized, we do not work in an association. We have relations with NGOs but we do not individually work there. We bring our queer identity everywhere with ourselves. If I open a cafe, I bring my presence there. For example, I always say, if I lose everything I have, I will plant parsley at my terrace, and sell it at the farmer’s market because I know and trust myself that I will sell it differently. The fact that we’re doing this interview right now is in itself activism.

Merve: I know, you both run bars and clubs. What other works you do?

Deniz: I write. I have a persona that I try to keep alive, so that it can keep me alive later. I do music. I started writing a theater play. Besides that I work, DJ and perform. I take care of animals. I spend most of my time for these things than running my bar and club.

Üzüm: I run a club. I DJ.

Merve: There is a systemic defamation strategy against the LGBTQI2+ movement. The statement „Islam recognizes adultery as one of the greatest harams. It curses homosexuality“ dated April 24, 2020 of Ali Erbas, the Director of Religious Affairs in Turkey has been one of the most debated discrimination discourses of recent months. No legal sanction was brought against this homophobic statement. What are your demands against this and similar homophobic discourses?

Üzüm: Since we are not legally recognized and cannot morally be categorized under normative “ethics”, defamation has always existed. Of course, it is not that easy to exist in a gender binary system. Our individual memories are quite strong. I think, this is important. Unfortunately, every LGBTI+ individual, regardless of their socio-economic class or cultural background, records the discrimination they experience. Everytime and everywhere. I think queer memory exists somewhere else, a place far from where the forgetful character of the cis-heterosexual memory exists.

However, of course censorship is a reality. Especially in the previous two decades several sad events took place in Turkey. Sending transgender people into exile, the torture from the police, being not welcomed in the neighborhoods.

As a result of globalization and increase of the foundations focusing on LGBT+ themes, people start to get organized around beginning of 2000s. The demonstrations, initiatives, media visibility and international collectivity brought visibility and the case opened against Lambda was dismissed. Lambda Istanbul continued to exist as a foundation. The intention of this case was to prevent foundation work. The win of this case is a legal achievement.

In Turkey there is a law called „Public Morality“, there are no laws explicitly forbidding homosexuality. On the contrary, I am a trans woman who has gone through the whole process, who received her identity card and I have 100% equal rights with cisgender women.

The statements of the Directorate of Religious Affairs or other conservative discourses do not negatively affect me. Of course I am concerned. The homophobic attacks in Turkey arises from this kind of statements, and bashes those who are not cis males. The criticism of Directorate of Religious Affairs on LGBTI+ is like beating someone who is not fasting during Ramadan. We have essentially more important problems. Of course, we can and shall resist against such discourses. But Directorate of Religious Affairs is one of the channels where the state expresses itself best. These aggressive discourses, in short, seem to me like the fluctuations on stock market.

Deniz: I do not pay attention to the defamation of the state nor the society. I am subjected to attacks and phobic approaches but I know how to stand against them. When one claims and reinforces his existence, one knows how to deal with what and when. We are kids who since they started to crawl claimed their existence. We claimed our existence at primary school, at university, at work life, or when we were unemployed. We have a very high threshold of endurance. Holding no fears make one freer. I am not afraid of Directorate of Religious Affairs but I am afraid of being unemployment in spite of all my labor. The exploitation of my labor, the bereaving of my right to live are more primary concerns of mine. Since years we talk about the statements of state officials or Directorate of Religious Affairs. I don’t expect them to utter something good, if they do, it’s great.

When I am subjected to sth like this, I put what we have won on one side and what we have lost on the other side. I recall the time when we started the first Pride Parade in 2003. I had read the press text and since it was the first Pride Parade, it was streamed on all the main TV channels, and published in all newspapers. That’s how my family learned about my queer identity. When I came to Istanbul with no money in my pocket in 1999, my only plan in life was to exist freely with my queer identity. I didn’t reveal anything to my family until 2003. I came to Istanbul with a wish that I wanted my family to hear about my identity in a very sensational way. And it happened so. It’s high time that they shall get afraid of us.

Merve: I am living and working in Berlin, Germany since February 2015. One of the problems which bugs me here is the racist, colonizing and white-hetero dominant European mentality which capitalizes the social and political unrests and freedom movements in other geographies that are made “third world countries” by the same mentality again. My experience is that the visible narrative here is still about “sacralizing the white heteronormativity” which results with rainbow marketing, instead of a reflected transformation for the liberations of marginalized groups. Do you have any observations about this?

Üzüm: I came to Berlin for a gig and I was subjected to transphobic attack in a bar there. In the West, the LGBTI+ perception is imposed by cisgenders. Despite all the negative parameter, Turkey is a transgender people’s country cause there is a queer-fem visibility here.

The “Transgender Equality Manifesto” published by the Pembe Hayat Derneği on June 18 is for example is issued against this patronizing discourse. We thought that we deserve a day. Because of my health issues, I couldn’t take part in the formation of the manifesto text. There are commemorations for those who died at Gezi Park protests or at Sivas Massacre. There are commemorations for a lot of cis-men who are known as revolutionists. So we thought, why not we should not have an equity day? Of course, as the individuals of the movement we would take action. My friends, may they live long, came up with a great idea. They asked from transgender people to write their own manifest. They asked me a manifest about health since I am experienced on it. But I didn’t participate in the writing of the manifest because of personal reasons and because I wanted to give place to younger friends.

It might be too late for a lot of things but a queerfeminism is blossoming within mainstream feminism and I believe this queerfeminism will stand against mansplaining capitalism. I see queerfeminism in all rebellions. Transgender movement, LGBT+ movement is also queerfeminist rebellions. The struggle against masculinity is very important.

Deniz: Feminist movement could embrace trance woman murders way before. Trance woman murders have not been and still isn’t recognized as femicide. If there had been public reactions against these murders, the situation could have been very different.

Merve: What is a sensitive and reflective international solidarity for you?

Deniz: I was also subjected to transphobic attack in Berlin and immediately returned home. Looking at similar fashion styles and the discourses in Berlin, I think there is a word-perfect situation there. I was discriminated because I didn’t fit in their queer, drag, transgender understanding. Every country strives for its own struggle. Therefore I know the western solidarity will not save me. I focus on our own spaces, what can we do here, how can we open up spaces where we can breath. I am interested in fighting against TERFs and fascists.

The Berlin visit was my first abroad visit. I observed an orientalist perspective in Berlin, like if I, as someone from Middle East, am going to make music, they expect an arabic touch and a belly dancer. The western perspective is like „Oh, what terrible lives they might have in Turkey, luckily they are now in the lands of freedom”. I think the subtext of these discourses is: „Whatever you do, you will not be equal to me.“ However, I for example can sometimes walk in my drag persona freely in Taksim without experiencing one single attack. The “Transgender Equality Manifesto” published by the Pembe Hayat Derneği on June 18 is for example is issued against this patronizing discourse.

Üzüm: There is a very broad answer to this question. I think the queer energy here is much more solidarist. I think, the focus should be on how the West will equalize itself with the queer solidarity in Turkey.

*The photo is from Ülker Sokağı (Ülker Street)