It is 1986. The times arabesque music is banned at Turkish Radio and Television Corporation, (TRT). It’s Bergen’s first appearance on TV. The gray-haired man in suit, who presents the program enters in the nightclub where Bergen takes stage while talking about Dede Efendi with an agitated tone. Bergen is singing the „The woman of Agonies“ in her white dress, her blond hair falling over her face.

“I am neither the first nor the last one

spending her years over the path of suffering,

Life is crushing me into pieces

I’m the woman of agonies. “

Then the interview begins:

“We know you as an arabesque artist. What do you think about Ottoman Music?” asks the man with his poetic and state-ruled Turkish and tone of voice.

Bergen answers “I love arabesque and happily sing it.”

“Why?” asks the man.

„The suffering I have experienced, my personal problems,“ says Bergen with a mocking expression on her face, she is bored from her statements, she is bored from the answers and she is bored from the man doing the interview. Of course the man can’t ask „What have your suffered?“ He cannot ask „What happened to your eye?“, „Why are you banned on performing on the TV screens of the state?“ The man is longing for the lost Ottoman Music, Bergen is longing for her lost youth.

Early in the morning of August 15, 1989 she is shot dead in Pozanti, Adana by her partner whom she divorced. This would be Bergen’s second appearance on the TV channel of the state. Her murderer was released after spending 7 months in prison. What reminds behind are these lyrics of a song of Bergen:

“My God, even if you forgive

your wicked creatures,

I will not.

even you forgive

all demons,

I will not.”

This scream of Bergen becomes a song of rebellion for all of us.

There is another person in those years who is not only forbidden to appear on the TV screens of the state but also cannot take stage anywhere in Turkey. And this person even started their artistic life singing Itri Mustafa Efendi, Dede Effendi. This person can challenge the seniors of the senior ones of the state with their Turkish Music knowledge and voice. Bülent Ersoy opens her breasts at the Izmir Fair, where she takes stage in August 1980, shortly before September 12 coup d’état. Thereupon, an investigation is opened against her and she is arrested and put in prison after insulting a judge. Right after this, the banned periods begin for her. Since Turkey doesn’t recognize yet transsexualism, she is not given a female identity even though she goes through the operation. She is legally recognized as a man and it is decreed that she can only take stage at nightclubs wearing men’s clothes. Because „transvestite and transsexual“ artists are forbidden to perform according to the September 12 coup d’état. She struggles with suicidal thoughts. She is sentenced to a life in exile. In her words “the seats she would take a sit collapses.” Bülent Ersoy, who cannot not take stage because of the bans exposed on her, is forced to leave her beloved country. She consults to cinema to make a living. She tries to reach people by existing in records and movies with her songs. Her songs are gradually turning into rebellion. With her song „I object“, she becomes the voice of many people who experience the same trouble:

„What do I owe to these troubles?

They don’t leave me in peace

Why I am so obsessed with happiness

It doesn’t make me miss hell“

This song whips at the face of those who make people of the earth not miss hell. Just like many songs of her. She gains her identity in 1988 with the law that is introduced under her leadership. She returns to her beloved land.

An excerpt from the interview she gave to İzzet Çapa:

„What can be more important than the freedom of a person? Who will claim my right? Will they be able to return the lost 8 years of my life? The very best years of my youth spent like that. The seat I was sitting on collapsed, what more should I have experienced? Damm, I’m angry now.”

“So what do you feel now when Kenan Evren’s name is mentioned?”

“He doesn’t get my blessing! If I have to answer to someone, it will be the biggest director above. Who the hell is he that he punished me with a penalty that does not exist in any law? Unbelievable. May Allah prevent his early death, but even then he will not get my blessing. “

“I saw him on TV recently, in the process of trial. He seemed exhausted.”

“I saw him too. I was sorry first. Then I said to myself, “The seat you sat in for eight years collapsed, from sitting in the same place. Did he feel sorry for you? Dear Izzet Bey, the scale of the great director above never fails. I believe that ‚they will be judged here before heaven and hell!‘ He will either pay or pay for what he has done!

“Bülent Ersoy still feels sorry for those who gave her forty minutes of hell.”

“Tweezers in one hand, mirror in the other

Do I care about this world

Every day in another realm

Every day in another heart

I enjoy my day oh oh

I live my life I live oh oh? “

The song „Let me enjoy“, which was released years later, became the anthem of everyone who has won this struggle. Bülent Ersoy and others deserve to live their lives as they want. She continues to go beyond the ordinary with her songs, costumes and stance in life.

When I was asked “why arabesque”, I wanted to tell you my arabesque journey with the stories of these two women. Because these two lives are thousands of lives. Sometimes arabesque was Fatoş abla, who found comfort in a Bergen song after being exposed to her husband’s violence, sometimes it was “girl Nejat “ who was subjected to neighborhood transphobia and who would do belly dance listening to “Ablan Kurban Olsun Sana*” Arabesque was Yıldız Tilbe who drank her tee after saying “Nobody protected me. Only Allah does, I hope, Allah protects you as well” against the statements that “she was rescued from pimps.” Arabesque was sometimes Dilber Ay who stabbed the person harassing her and served her time and answered the questions “I didn’t doubt my decision a second.”

Was the story of these two women far from our lives? How many people are there who have not been subjected to or witnessed domestic male violence? How many people are there who have not suffered from the power of the state, men and laws? Isn’t it because of this shared story, years later, the name of Abdullah Dilipak, Lale Mansur, Bülent Ersoy and dozens more came together to carry a lawsuit against Kenan Evren? Isn’t it because of this shared story, the endless trials and struggle for dozens of women who are subjected to violence or killed? How far away was Harika Avcı from our lives who told that she was exposed to her boyfriends violence and stood barely on her feet with medications when the song “Sürünüyorum*” was playing in the background. Isn’t her artistic life again stolen because of a man?

The questions of information rulers like “What was arabesque music? What was it telling? Was it driving people into despair? “ would not end.

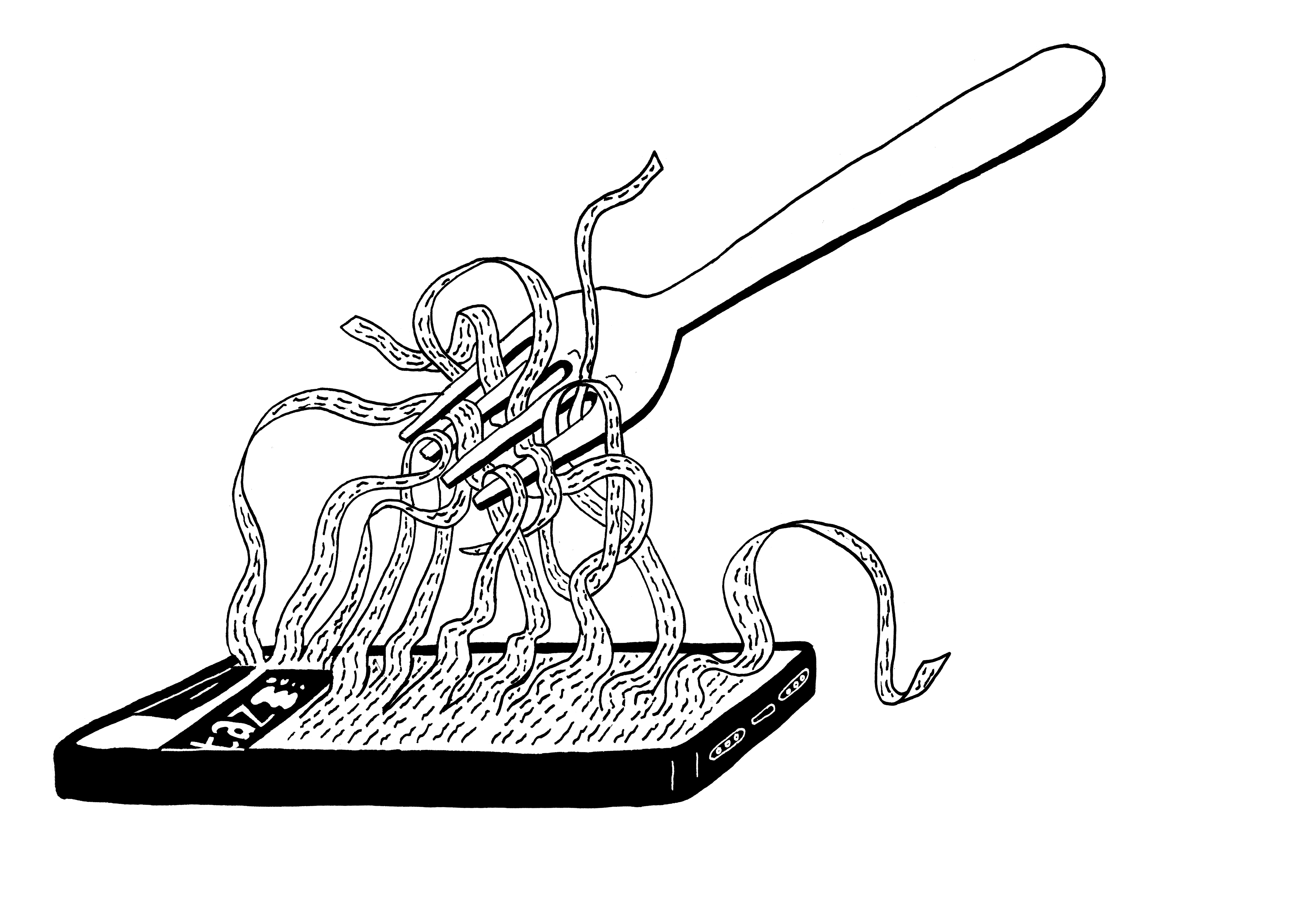

Arabesque is an attitude. It does not tell its problem indirectly. It tells the rebellion, love, pain and happiness quite directly. It is individual. It gathers and equates individuals who experience social inequalities, are marginalized and discriminated. It turns into a common scream. It confronts pain as an attitude. It doesn’t give up. It doesn’t let life be. Arabesque is the outcast sex worker of the neighborhood, the fagot who is hit by a stone on his head, the elder sister who is forced to marry, the bloody bed sheets laid on the balconies, the girls whose hairs are buzzcut by force, the boys whose hair are extended by force.

We can try to close the windows as much as we want not to hear arabesque playing, we can ask the minibus or taxi driver „could you please change the radio channel? We can make arabesque other, we can despise it, we can look down on it. One day we will all walk by a nightclub. One day children who are exposed to social discrimination, children who turn the volume of arabesque music up in their cars, children who are “grown up in gettos” pass by all of us. We definitely bump into a broken razor while walking. We definitely meet girls who carry razors between their legs.

There will always be sister Fatoşs or Girl Nejats who take refuge in songs. Do the Bergens ever disappear? Isn’t the water supply of a transgender person cut by their neighbors last week? Aren’t 22 women killed in February (I don’t know about March yet). Who knows which song did Eylül Cansın listened to before jumping to her death from the Bosphorus Bridge?

For me, arabesque is a 10-years old me cuddling my sister who in front of my eyes was subjected to her husband’s violence and crying in accompany of a Kamuran Akkor song, I was actually a fan of Madonna then. For me, arabesque is “Dilek Taşı” which became refuge of my child-self running from the kids of the neighborhood who were fingering me. Wasn’t Sinead O’Connor’s Nothing Compares 2 U arabesque which I listened to in tears the first time I fell in love?

Didn’t Sezen Aksu answer her question again in her song, when she said “The songs which don’t carry pain would have shortcomings”? Didn’t she make it clear that confrontation is the essential thing not ignoring the pain.

For me nowadays, arabesque is making fun of pain, standing in front of the it, looking into pain’s eyes and bursting out in laughter.

For me nowadays, arabesque is to be able to say:

“My life is spent in dark places

My heart is like a broken glass

Just don’t look at my face with hate

If I am bad, if I have failed, this is no one’s business”.

For me nowadays, arabesque is to be able to say:

„If you love me, you will sit at a table and drink with me“.

Recalling the saying „Geography is Destiny“, I tried to witness a small part of the suffering, rebellion of people who share the same destiny with me on this geography. “You name it”.

Whatever you name being in solidarity with those suffering, it doesn’t matter to me.

Jilet Sebahat

* A song of Bülent Ersoy

* A song of Ali Tekintüre