Bei dieser Hitze hängen die meisten Hausmeister schlapp rum, andererseits mehren sich die Verbrechen, begangen von Hausmeistern nach Feierabend – wenn man der Presse glauben darf. Wer auch dazu zu schlapp ist, schraubt sich wenigstens in Gesprächen zu immer abenteuerlicheren Gedanken hoch.

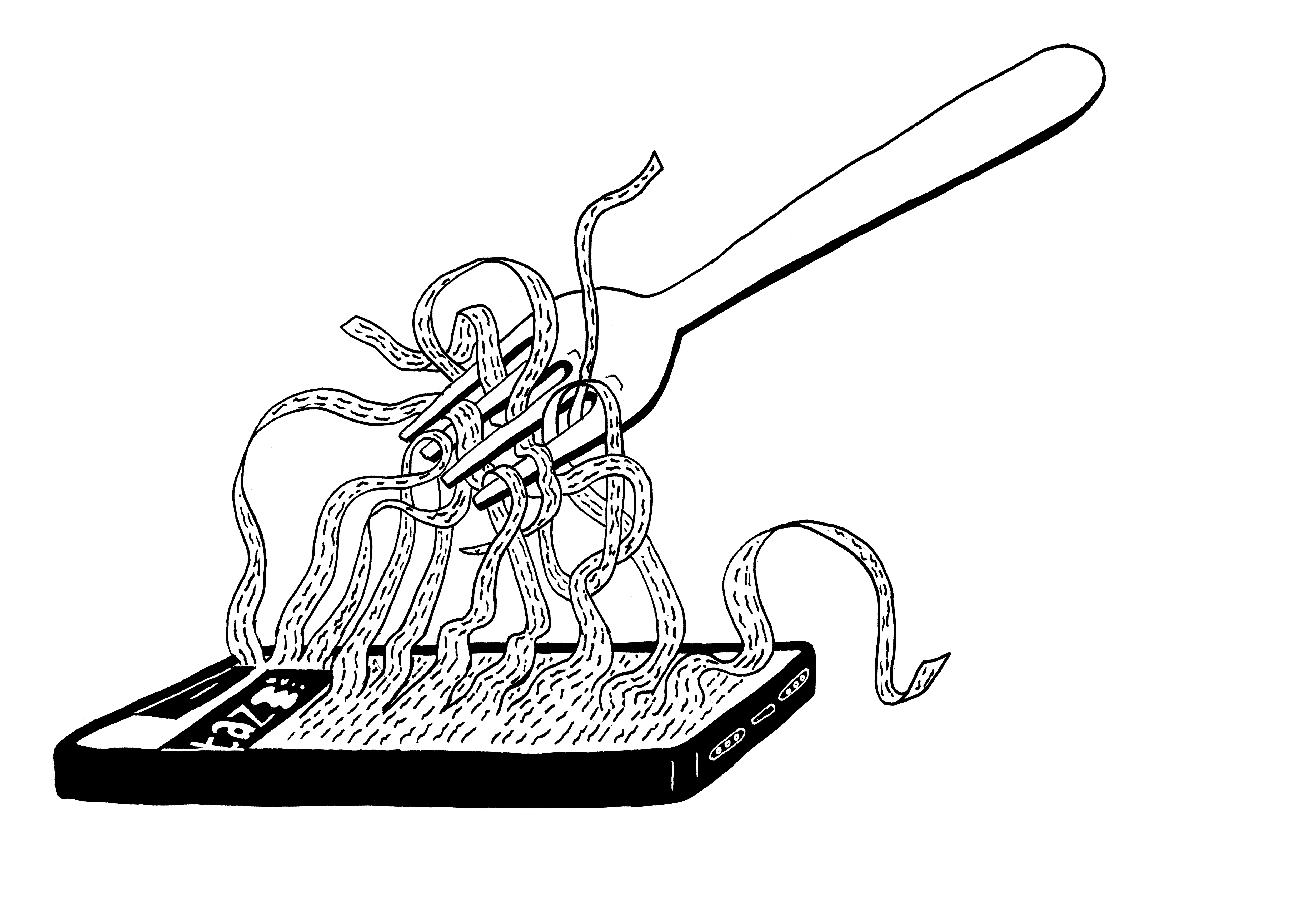

Neulich verstieg sich einer im Hausmeistertreff der ÖTV am Wannsee zu der These, dass die riesige Ansammlung von E.coli-Bakterien in unserem Darm, ohne die wir nicht leben können, unsere Träume, Wünsche und Willen mitbestimmt. Also wenn ich z.B. eine vegetarische Diät abbreche, weil ich plötzlich Heißhunger auf Hühnerbrühe habe, dann ist das vielleicht ein Wunsch oder Wille, den mein „Symbiont“ E.coli, der in einigen Varietäten auch zu einem „Parasiten“ werden kann, mir quasi vom Darm aus eingibt.

Schon der Wissenshistoriker Michel Serres fragte sich, ob „parasitäre Verhältnisse“ eine Ausnahme oder „nicht einfach das System selbst sind“? Ähnliches könnte auch und erst recht für „symbiotische Verhältnisse“ gelten, also bei mir und E.coli. In der Homöopathie kennt man „Miasmen“: das sind u.a. die von Bakterien hervorgerufenen „Krankheiten hinter den Krankheiten“ – Tripper, Syphilis und Tuberkulose. Alle drei bewirken einen gesteigerten Wunsch nach körperlicher Nähe und sexuellem Kontakt. Den drei „Erregern“ ist nämlich daran sehr gelegen – jedenfalls wenn sie sich ausbreiten, d.h. auf Nummer Sicher gehen wollen. Ihre Wirte machen es unter Umständen ja nicht mehr lange.

Wie kompliziert die Vorgänge zu seiner Verhaltensbeeinflussung verlaufen können, zeigen die verschlungenen, jedoch vollkommen zielgerichteten Wege des Parasiten „kleiner Leberegel“. Ein Vorstadium von ihm, Miracidien genannt, liegt im Gras und wird von einer Schnecke mitgefressen. Im Darm bildet sich aus der Vorform eine weitere: sogenannte Cercarien. Diese wandern in die Atemhöhle und werden sodann von der Schnecke als süßer Schleimbrocken ausgestoßen. Der Schleim wird besonders gerne von Ameisen gefressen. Im Bauch der Ameise entwickelt sich aus einer der vielen Cercarien ein „Hirnwurm“, der in das Ameisengehirn wandert, um von dort aus das Verhalten seines Wirtstieres zu beeinflussen. Dergestalt, dass es sich am Abend nicht in den Ameisenbau verzieht, sondern im Gegenteil die Spitze eines Grashalmes erklimmt und sich dort festklammert. Irgendwann kommt ein Schaf oder Rind und frißt das Gras mitsamt der Ameise und dem kleinen Leberegel. Und damit ist dieser am Ziel: Hier kann er sich entfalten – und erneut Miracidien produzieren, die dann über den Kot seines Wirtes abgesetzt werden. Durch den Verzehr von Rind- oder Schafsfleisch kann der kleine Leberegel auch in unseren Körper gelangen. Aber das ist von ihm nicht geplant. Im Gegenteil, denn unsere Scheiße landet selten auf Wiesen oder Weiden.

Anders ist es mit dem Saugwurm Bilharziose und dem Menschen: Seine im Wasser lebende Larvenform Cercarie dringt beim Baden oder Waschen in unsere Haut. Um da durch zu kommen, muß sie sich sehr gut mit dem Chemismus der Haut auskennen. Im Körper angelangt bilden die Larven sich zu adulten Würmern um, die in Blutgefäßen leben. Zur Ausbreitung legen die Würmer alsbald Eier, die dann über den Darm bzw. die Blase der Menschen (200 Mio sind weltweit von Bilharziose befallen) wieder ins Wasser gelangen, wo sie sich zu Miracidien entwickeln. Von dort müssen diese erst einmal in ganz bestimmte Wasserschnecken gelangen, in denen sie sich zu den für Menschen gefährlichen Cercarien entwickeln. Es gibt unterschiedliche Arten von Miracidien und sie suchen sich unterschiedliche Wirtsschneckenarten. Ihre hohe Spezialisierung hat zu einer extremen Unfreiheit der Wahl geführt, dafür ist sie darin äußerst präzise: Zur Arterkennung und Verständigung geben die Schnecken makromolekulare Glykoproteine ins Wasser ab, wobei ihre Artspezifität sich in einem bestimmten glycosidisch gebundenen Kohlehydratanteil entbirgt. Die Miracidien-Larven nun kennen diese „Sprache“, die sie mit einiger Sicherheit zur „richtigen“ Wirtsschnecke bringt.

Abschließend sei noch erwähnt, dass es einen anderen Saugwurm gibt, der im Gehirn eines Zwischenwirts angelangt diesen dahingehend beeinflusst, dass er in einer ganz bestimmten Wassertiefe schwimmt – wo er prompt von einer Fischart gefressen wird, auf die der Saugwurm es abgesehen hat. Der Parasit vermag also an der Höhensteuerung seines Zwischenwirts zu drehen. Aber dieser ist natürlich auch nicht dumm – und läßt sich laufend neue Gegenstrategien einfallen, es ist die reinst Waffenproliferation. „Genug, man muß die These wagen, daß überall, wo Wirkungen anerkannt werden, Wille auf Willen wirkt,“ meinte noch Nietzsche.

Viele Gehirnforscher gehen heute vom schieren Gegenteil aus: dass es keine „Willensfreiheit“ (und damit auch keine „Schuldfähigkeit“) gibt, weil wir genetisch, hormonal und synapsenmäßig sozusagen ferngesteuert sind. Das ist Biologie minus Leben.

Tja, das Leben kann so scheisse sein, mann muss sich nur mühe geben.