Das TimeOut Magazin London, Vorbild für alle Stadtmagazine dieser Welt, hat eine hervorragende Liste der besten britischen Filme zusammengestellt, die von einer illustren Jury gewählt wurden.

Die ganze Liste ist des Lesens wert, hier nur als Appetitanreger einige Listeneinträge, die ausdrücklich des Popblogs „Thumbs Up!“ bekommen:

97. 28 Days Later… (2002, Danny Boyle)

„The zombie segments, while tense, violent and gruesome, are a sideshow to the story’s main thrust: our predisposition towards outright selfishness and savagery when even our most basic of needs are whipped from beneath our feet.“

95. London to Brighton (2006, Paul Andrew Williams)

„A rape, revenge and road movie (in that order) about a distressed young girl (Georgia Groome) helped by a prostitute (Lorraine Stanley – stunning) to flee a gang of tinpot hoods, it’s a film where no shot, line and character is wasted.“

94. 24 Hour Party People (2002, Michael Winterbottom)

„The film remains one of the purest pleasures in modern British cinema: scrappy, inconsistent, inventive, insightful, heartfelt and wickedly funny.“

92. Dead Man’s Shoes (2004, Shane Meadows. Dt. Titel: „Blutrache“)

„Shane Meadows’s fourth film shows the importance of staying true to your instincts. ‘Dead Man’s Shoes’ was an uncompromising and successful attempt by Meadows to rediscover his old voice.“

90. Blue (1993, Derek Jarman)

„With this avant-garde work, Jarman drew attention to him, his work, sexuality and illness and made an unembarrassed, deathbed claim for art itself.“

88. This Is England (2006, Shane Meadows)

„The film established Meadows in a league of his own when it comes to naturalistic, comic dialogue and wringing sensitive performances from young cast members.“

60. The Long Good Friday (1980, John Mackenzie, Dt. Titel: „Rififi am Karfreitag“ (!))

„John Mackenzie’s gangster thriller still has great energy and momentum and isn’t a patch on recent pretenders to its throne.“

57. 2001 – A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

„Okay, so the director, money and most of the cast are American, but it was shot here, dammit, so we’re claiming ‘2001’ as our own. True, the same could go for most of Hollywood’s bigger-budget ’70s and early ’80s efforts (‘Star Wars’, ‘Raiders’, ‘Aliens’…), but none of those films feels remotely British whereas, in a strange way, ‘2001’ does.“

54. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1974, Terry Gilliam & Terry Jones)

„An absurd and very loose conjoining of the Arthurian and Holy Grail legends, the film remains one of the Pythons’ most memorable piss-takes.“

47. Blow-Up (1966, Michelangelo Antonioni)

„Antonioni twists his film to be about the nature of making, collecting and editing images, also suggesting that – try as we might – life is a first-hand experience that no camera can ever really capture.“

45. Repulsion (1965, Roman Polanski)

„The film remains influential on both horror directors and those looking to represent mental breakdown on film (look at Darren Aronofsky’s ‘Black Swan’).“

44. Sabotage (1936, Alfred Hitchcock)

„‘Sand! Sabotage! Deliberate! Wrecking!’ are the terse first words of Hitchcock’s atmospheric, exciting and sometimes funny, 1936 London-based suspenser, adapted from Joseph Conrad’s ‘The Secret Agent’.“

34. A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick)

„Swap Beethoven for heroin, and Stanley Kubrick’s scandalous 1971 Moog-mare based on Anthony Burgess’s novel might work as a forerunner to ‘Trainspotting’. Does it stand up psychologically? Probably not. But as an example of a work in which the filmmaking style matches the tone of the material, it’s peerless.“

32. Get Carter (1971, Mike Hodges)

„A cold, impossibly grimy film, ‘Get Carter’ is a ‘Third Man’ for the three-day week generation that drags you through the sulphurous back rooms of hell.“

29. Peeping Tom (1960, Michael Powell)

„It’s the story of a Teutonic loner named Mark (the ultra-creepy Karl Böhm) who carries on the work of his father by seducing women, luring them in front of his camera and dispatching them with a giant metal spike.“

24. Brazil (1985, Terry Gilliam)

„Grim, confusing and scattergun it may be, but ‘Brazil’ is a film rich in deep and diverse pleasures, many of them uniquely British“

20. Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979, Terry Jones)

„three decades on, ‘Life of Brian’ still dominates our perceptions of organised religion (and organised resistance) and their many obfuscations, untruths and double standards in a way that is not just remarkable, but extremely heartwarming.“

19. Barry Lyndon (1975, Stanley Kubrick)

„The shape of a life, a human’s rise and fall, rendered as an epic, mesmeric, suffusing slow dance of immersive cinema – and therefore, not only Kubrick’s most beautiful but also his most empathetic and understanding work.“

15. Withnail & I (1987, Bruce Robinson)

„its inspirationally funny script, spot-on performances and evocative soundtrack, helping to combine a gloriously mocking elegy for Britain’s supposedly Swingin’ Sixties with a moving, bittersweet distillation of personal memory and of friendship recalled.“

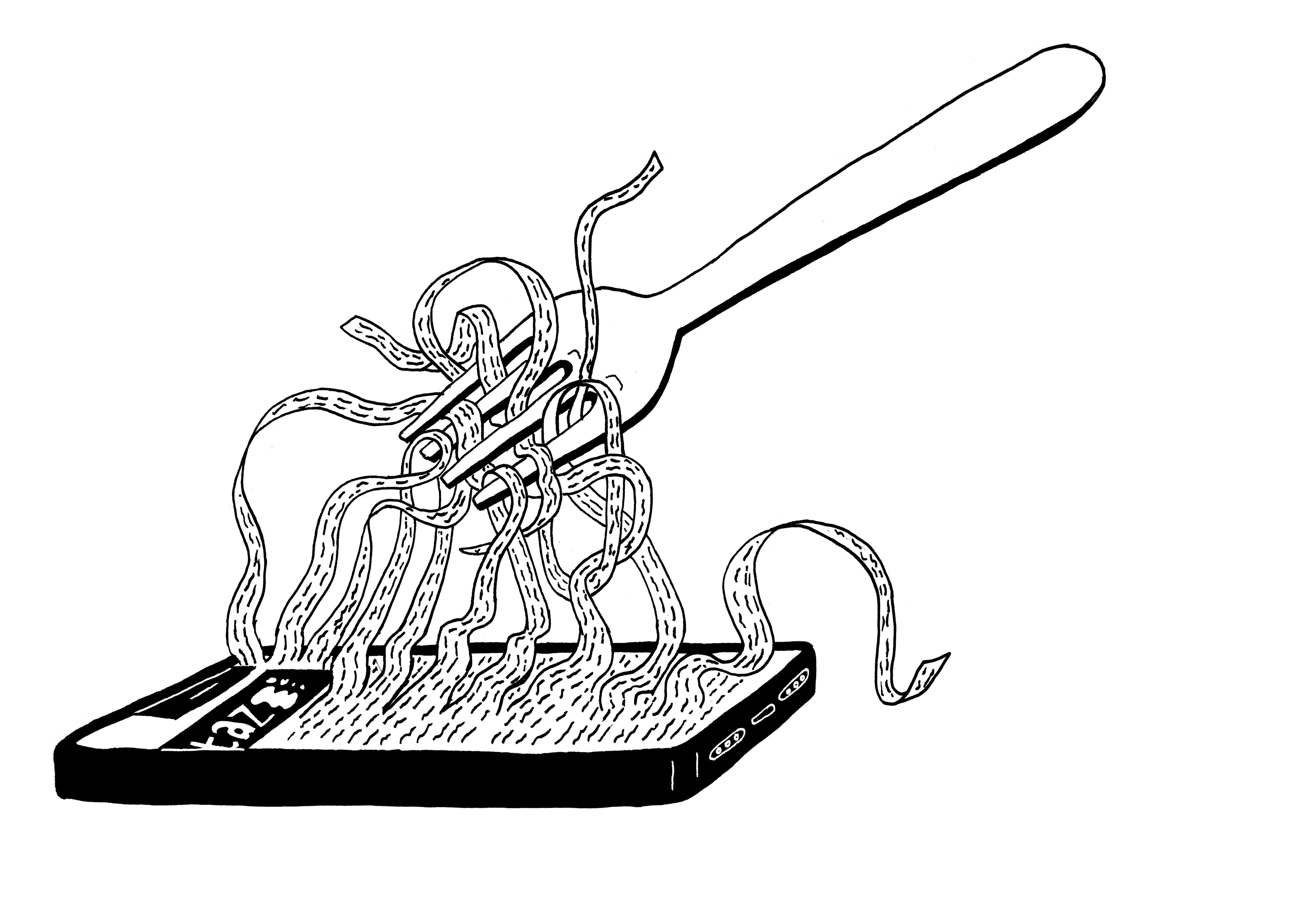

10. Trainspotting (1996, Danny Boyle)

„what makes ‘Trainspotting’ stand above the crowd is the industrious way in which he uses editing and camera movement to convey time, activity, violence, love, ecstasy and pain. Plus, is this the greatest opening five minutes ever?“

9. If… (1968, Lindsay Anderson)

„The film’s attack on tradition and authority undoubtedly encapsulated and tapped into the counter-cultural mood of the time – but its themes of community, leadership, oppression and rebellion, as well as its edge of comic surrealism and weird fantasy, continue to endure more than forty years later.“

4. Kes (1969, Ken Loach)

„‘Kes’ remains devastating, the peak of British realism and one of the most heartbreaking works in all of cinema.“

2. The Third Man (1949, Carol Reed)

„The genius at the core of this superlative, bible-black Euro noir is the way it teases you in to thinking that you’re watching a disposable pulp yarn about an honest schlub who touches down in a crumbling, post-war Vienna and won’t rest until he uncovers a conspiracy concerning the death of an old pal.“

1. Don’t Look Now (1973, Nicolas Roeg)

„we can just accept it as a movie whose every glorious frame is bursting with meaning, emotion and mystery, and which stands as the crowning achievement of one of Britain’s true iconoclasts and masters of cinema.“

Ja, ich hatte mir die DVD mal aus England bestellt.

Muss allerdings sagen, dass das ohne Untertitelmöglichkeit schon ein hartes Stück Arbeit war, alles zu verstehen…