Christmas time was story time. My childhood memories of Advent season are filled with them. I remember fairy-tales about mystical creatures, gospel readings about compassion and forgiveness, and movies about love and family. Christmas stories are magical stories. Regardless of whether or not you were religious, it seemed that Christmas gave you permission to anticipate the better and hope for the best. Yet, on the 26th of December 2004, seemingly unearthly forces unleashed unimaginable horrors on an earthly paradise and turned it into hell. A Tsunami in the Indian Ocean caused flood waves of up to 35 meters high, hitting the coast lines of 15 South Asian and South-East African countries at speeds of up to 800km/h. The waves claimed somewhere between 230 000 and 260 000 human lives. Only a couple of years later though, this tragedy had vanished from public memory. Christmas proved to be impervious to the deadliest sudden onset disasters of our time.

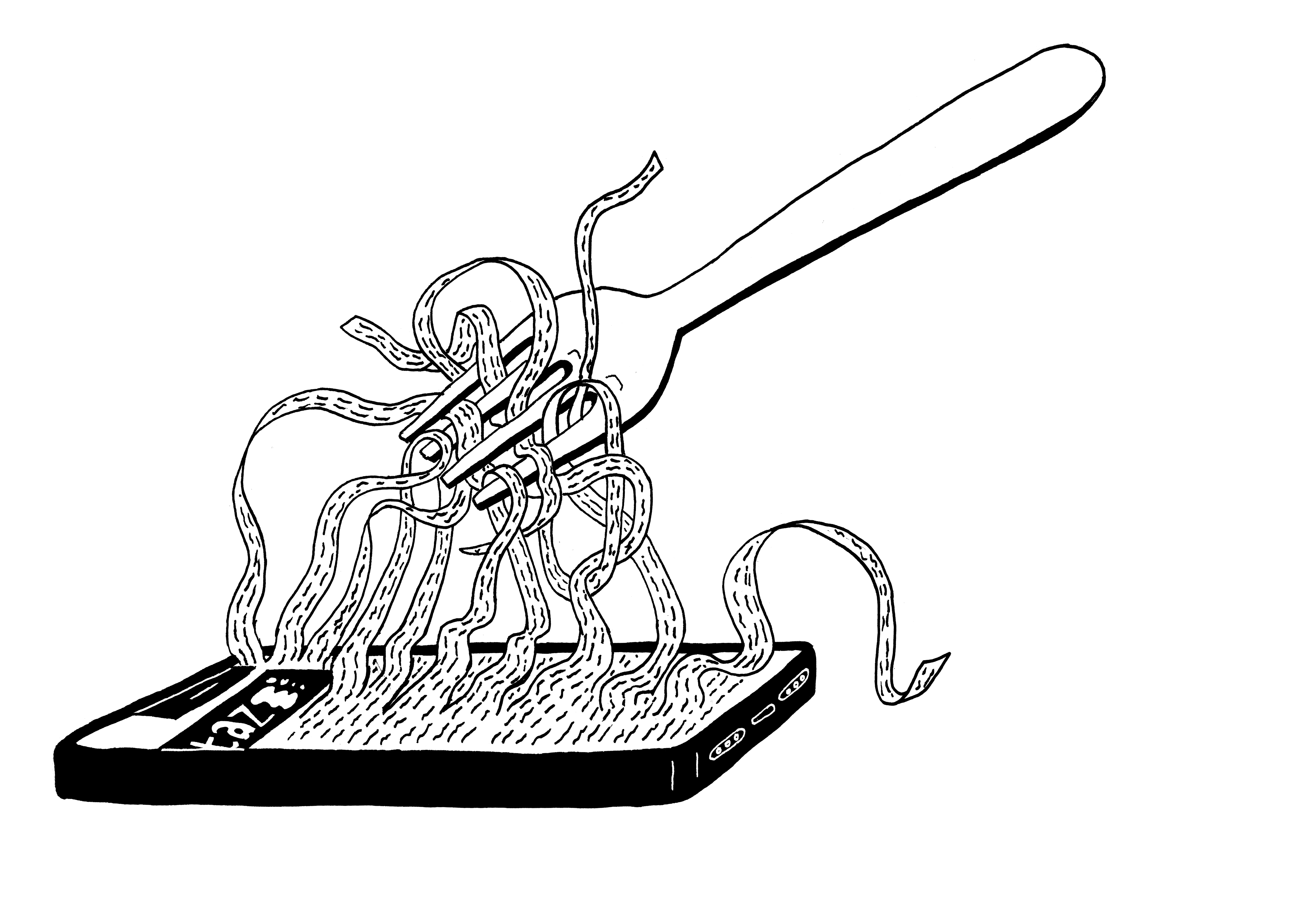

Coca Cola’s marketing campaign of dressing Santa Claus in his red-white coat has had a more lasting effect on this holiday than that Tsunami, which is only one indication of how far its contemporary makings are removed from its Christian origins. Today, Christmas consumerism has a firm grip on all of us. In Christian and non-Christian households alike people go out of their way to satisfy at least some Christmas conventions, or find themselves compelled to explain why they don’t. Salman Rushdie, an atheist born to a Muslim family portrays the all-encompassing power of Christmas conventions as he describes his eventual surrender to all of them, going as far as describing the non-exchange of presents between him and his sister as an act of defiance. Similarly, my mother who could never wrap her mind around the Christmas tree business, find herself in need every year, to explain why she hangs her Christmas ornaments on her living room cactus. Why support the killing of trees, when you already have a large, sturdy and branchy plant at hand that does not mind some fairy lights? Many of today’s Christmas rituals demand consumption of us and in almost all pre-pandemic advent seasons, I found myself on frantic last-minute shopping sprees and marathon baking and gift-wrapping sessions, which, unlike Christmas songs had me believe, did not feel magical, but stressful. Why am I telling these anecdotes on an international law blog? Because they are to some extent reminiscent of how I feel about international law at times.

The 1990s and Virtuous Internationalism

When I was eight years old, international law entered my life through a story: a magazine story about the work of an international human rights lawyer. I decided then and there that this is what I wanted to be one day. The 1990s were the decade of human rights, of compassion, of Lady Diana and Mother Teresa. The evening news were filled with images graphically depicting the suffering in former Yugoslavia or in Sierra Leone, the horrors of the Rwandan genocide, the misery of global hunger and the loss of far too many lives to AIDS. At the time, German mainstream media portrayed internationalism as the universal solution to all of these crises. In my childhood mind, international relief agencies stood for love and care for others, international courts and tribunals represented justice and the United Nations was synonymous to peace. It did not register reports of failing UN peacekeeping missions or of the ‘Battle in Seattle’ associated with the WTO Ministerial Conference of 1999. Just like Christmas, the idea of international law was filled with stories that made it magical.

The 2000s Disillusionment

The aftermath of 9/11 shook up my belief in the all-healing powers of internationalism. Through time and training, I learned to accept that international law is not the result of compassion, but of necessity; that it bears more marks of conflict than of unity and; that it is more amenable to the powerful than it is to the poor. As I had done with Christmas, I gradually lowered my expectations towards international law and perhaps, this is a good thing. Just as it is the case with Christmas, international law’s ritualization of expectations and behaviour can feel confining at times.

Think for instance of the conventional wisdom of its sources, which leads us to value less ambitious legal bindingness over less rigid but more ambitious legal forms, a phenomenon that we witness at each and every UNFCCC-COP. Furthermore, the flip-side to ritualized legal behaviour, i.e., practices that we associate with legal certainty is that it becomes difficult to imagine a world without them, even in instances, in which they are no longer timely. Just as much as we struggle imagining Christmas without Christmas trees, it sometimes feels as if it is not possible to imagine a world without the mid-20th century creatures of bilateral investment treaties, regardless of our acute awareness their many many problems. When ritualized behaviour in international law does change, the nature of such change might be far removed from the changes that we international lawyers would have liked to see. In light of the inhumane conditions that it continues to produce for refugees at Europe’s outer borders, I know that I am not the only one to wonder about the humanity of international law. In such moments, my frustration grows worse, when I recall how amenable it has been to global efforts against terrorism and organized crime.

De-Ritualizing International Law

Just as much as Christmas, international law today is defined by its rituals. These rituals shape our common understanding of international law and set the standard for ‘minimum expectations’ or ‘appropriate behaviour’. Just as it is the case for Christmas, everyone has their own version of international law. Mr. Putin’s version of international law may be quite different from that of Mr. Macron. Global campaigns against blood diamonds, against agrobusiness, against Wall Street, against vaccine mandates, or against climate change, they all have their own version of international law. I may not like some of these versions of international law, even doubt whether they even still qualify as such. Just as it is the case with Christmas however, I suspect that de-ritualizing international law will make it more meaningful eventually.

This post was also published on Völkerrechtsblog