***

Der Bär flattert arrogant in westlicher Richtung.

***

Albert Blaser nimmt seine morgendliche Chocolat à la vanille

***

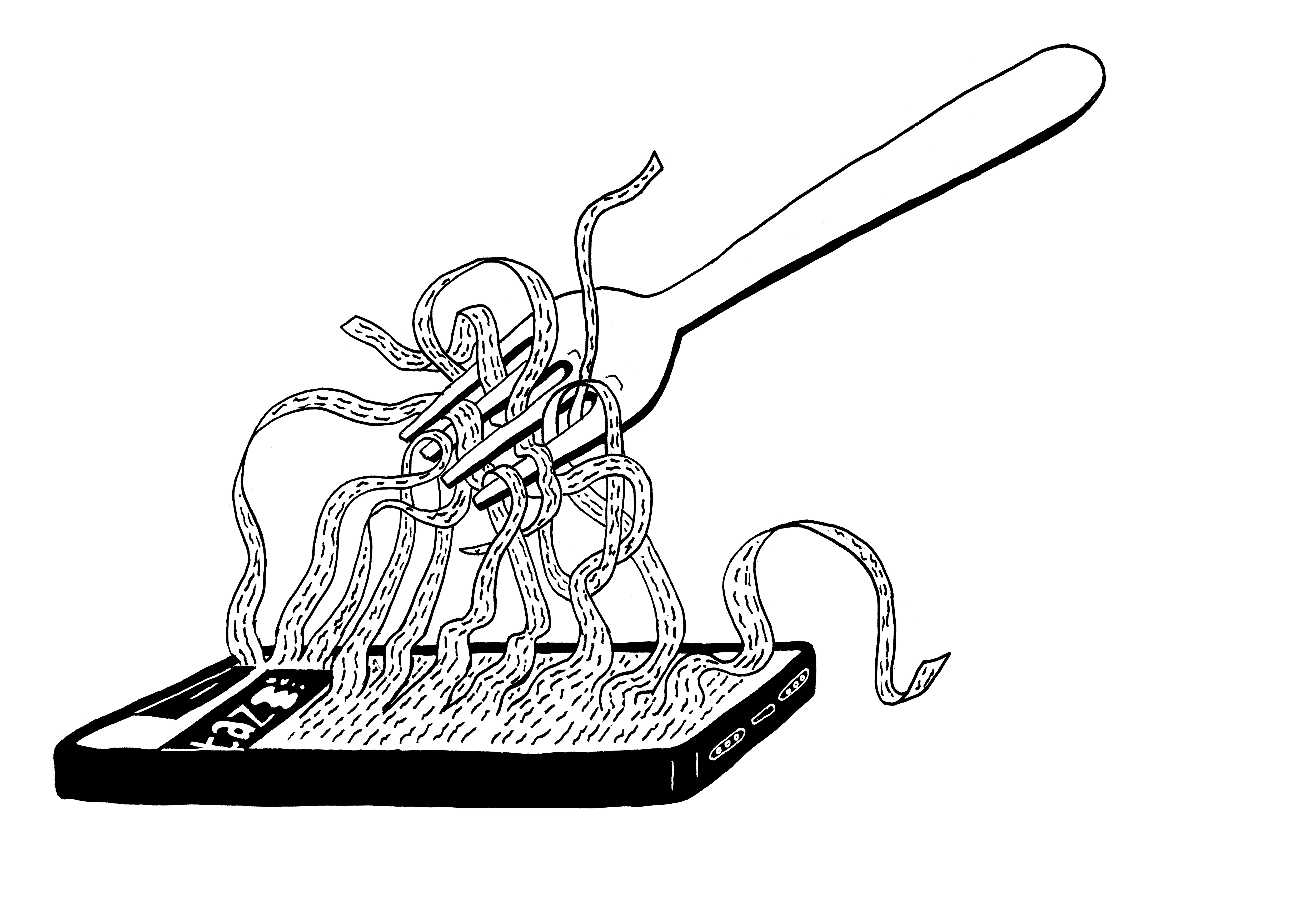

Natürlich geht die Blasiertheit nicht auf Albert Blaser zurück, den Chef des berühmten Pariser Restaurants ›Maxim’s‹. Aber es paßt einfach zu gut um wahr zu sein, auf jenen Maitre d’hotel, dessen Arroganz und Reserviertheit es schaffte, den Gästen, die einen Tisch erhielten, das Gefühl zu geben, in das Allerheiligste eingelassen worden zu sein. Die Comtesse Guy de Toulouse-Lautrec schrieb über ihn: »Jahrelang beobachtete ich, wie er am Eingang zum Hauptraum des ›Maxim’s‹ präsidierte. Leidenschaftslos und ernst wie ein Pinguin wandte er seine kalten blauen Augen den Neuankömmlingen zu und identifizierte jedes Gesicht mit einem Namen aus dem Vorrat seines unfehlbaren Gedächtnisses. Ich kann nicht behaupten, daß wir Freunde waren. Albert hatte keine Freunde. Alles, was er besaß, waren Verbindungen, die allerdings waren lückenlos, vom Aga Khan bis zum Herzog von Windsor, nicht zu sprechen von den unzähligen Herzoginnen, Filmstars und Millionären auf seinen Gästelisten. Alberts erfolgreiche Karriere und der Wiederaufstieg des ›Maxim’s‹ beruhte auf seiner Kunst, die Snobs zu snobben.«

Aber Snobismus ist nicht alles. Das ›Maxim’s‹ war berühmt für sein Essen, und als Blasers bekannteste Erfindung gilt die ›Seezunge Albert‹: In frischen Brotkrumen und Butter gewälzt, danach mit einem Schuß Absinthe knusprig gebacken. Von diesem legendären Fischgericht hörte ich zum ersten Mal in einer ärmlichen Hütte in der Nähe von Köln. Mehr darüber in unserer heutigen Kolumne in der jungen Welt.

(BK / JS)

Liebe Barbara, lieber Jörg,

ein schöner Text in der jungen Welt, dazu fiel mir George Orwells Schilderung über den Dreck in der Küche der Reichen ein

http://www.george-orwell.org/Down_and_Out_in_Paris_and_London/13.html

„In the kitchen the dirt was worse. It is not a figure of speech, it is

a mere statement of fact to say that a French cook will spit in the soup – that is, if he is not going to drink it himself. He is an artist, but his art is not cleanliness. To a certain extent he is even dirty because he is an artist, for food, to look smart, needs dirty treatment. When a steak, for instance, is brought up for the head cook’s inspection, he does not handle it with a fork. He picks it up in his fingers and slaps it down, runs his thumb round the dish and licks it to taste the gravy, runs it round and licks again, then steps back and contemplates the piece of meat like an artist judging a picture, then presses it lovingly into place with his fat, pink fingers, every one of which he has licked a hundred times that morning. When he is satisfied, he takes a cloth and wipes his fingerprints from the dish, and hands it to the waiter. And the waiter, of course, dips HIS fingers into the gravy–his nasty, greasy fingers which he is for ever running through his brilliantined hair. Whenever one pays more than, say, ten francs for a dish of meat in Paris, one may be certain that it has been fingered in this manner. In very cheap restaurants it is different; there, the same trouble is not taken over the food, and it is just forked out of the pan and flung on to a plate, without handling. Roughly speaking, the more one pays for food, the more sweat and spittle one is obliged to eat with it.

Dirtiness is inherent in hotels and restaurants, because sound food is

sacrificed to punctuality and smartness. The hotel employee is too busy

getting food ready to remember that it is meant to be eaten. A meal is

simply ‚UNE COMMANDE‘ to him, just as a man dying of cancer is simply ‚a

case‘ to the doctor. A customer orders, for example, a piece of toast.

Somebody, pressed with work in a cellar deep underground, has to prepare

it. How can he stop and say to himself, ‚This toast is to be eaten–I

must make it eatable‘? All he knows is that it must look right and must be ready in three minutes. Some large drops of sweat fall from his forehead on to the toast. Why should he worry? Presently the toast falls among the filthy sawdust on the floor. Why trouble to make a new piece? It is much quicker to wipe the sawdust off. On the way upstairs the toast falls again, butter side down. Another wipe is all it needs. And so with everything. The only food at the Hotel X which was ever prepared cleanly was the staff’s, and the PATRON’S. The maxim, repeated by everyone, was: ‚Look out for the PATRON, and as for the clients, S’EN F–PAS MAL!‘ Everywhere in the service quarters dirt festered–a secret vein of dirt, running through the great garish hotel like the intestines through a man’s body.

Apart from the dirt, the PATRON swindled the customers wholeheartedly.

For the most part the materials of the food were very bad, though the cooks knew how to serve it up in style. The meat was at best ordinary, and as to the vegetables, no good housekeeper would have looked at them in the market. The cream, by a standing order, was diluted with milk. The tea and coffee were of inferior sorts, and the jam was synthetic stuff out of vast, unlabelled tins. All the cheaper wines, according to Boris, were corked VIN ORDINAIRE. There was a rule that employees must pay for anything they spoiled, and in consequence damaged things were seldom thrown away. Once the waiter on the third floor dropped a roast chicken down the shaft of our service lift, where it fell into a litter of broken bread, torn paper and so forth at the bottom. We simply wiped it with a cloth and sent it up again. Upstairs there were dirty tales of once-used sheets not being washed, but simply damped, ironed and put back on the beds. The PATRON was as mean to us as to the customers. Throughout the vast hotel there was not, for instance, such a thing as a brush and pan; one had to manage with a broom and a piece of cardboard. And the staff lavatory was worthy of Central Asia, and there was no place to wash one’s hands, except the sinks used for washing crockery.

In spite of all this the Hotel X was one of the dozen most expensive

hotels in Paris, and the customers paid startling prices. The ordinary

charge for a night’s lodging, not including breakfast, was two hundred

francs. All wine and tobacco were sold at exactly double shop prices,

though of course the PATRON bought at the wholesale price. If a customer

had a title, or was reputed to be a millionaire, all his charges went up

automatically. One morning on the fourth floor an American who was on diet wanted only salt and hot water for his breakfast. Valenti was furious. ‚Jesus Christ!‘ he said, ‚what about my ten per cent? Ten per cent of salt and water!‘ And he charged twenty-five francs for the breakfast. The customer paid without a murmur.

According to Boris, the same kind of thing went on in all Paris

hotels, or at least in all the big, expensive ones. But I imagine that the customers at the Hotel X were especially easy to swindle, for they were mostly Americans, with a sprinkling of English–no French–and seemed to know nothing whatever about good food. They would stuff themselves with disgusting American ‚cereals‘, and eat marmalade at tea, and drink vermouth after dinner, and order a POULET A LA REINE at a hundred francs and then souse it in Worcester sauce. One customer, from Pittsburg, dined every night in his bedroom on grape-nuts, scrambled eggs and cocoa. Perhaps it hardly matters whether such o people are swindled or not.“