Gestern hatte ich – zwischenbilanzierend – über die bisherigen sieben Supreme Court-Entscheidungen zur US-Regierungspolitik seit Beginn von Donald Trumps zweiter Amtszeit als US-Präsident berichtet und angekündigt:

„Teil II. (‚Und wie geht es nun weiter?‘) folgt wahrscheinlich am Dienstag mit folgenden Abschnitten:

- Staatsangehörigkeitsrecht

- Merit Systems Protection Board und National Labor Relations Board

- Ausschluß von transgender-Personen aus dem US-Militär

- DOGE-Zugriff auf Sozialversicherung.“

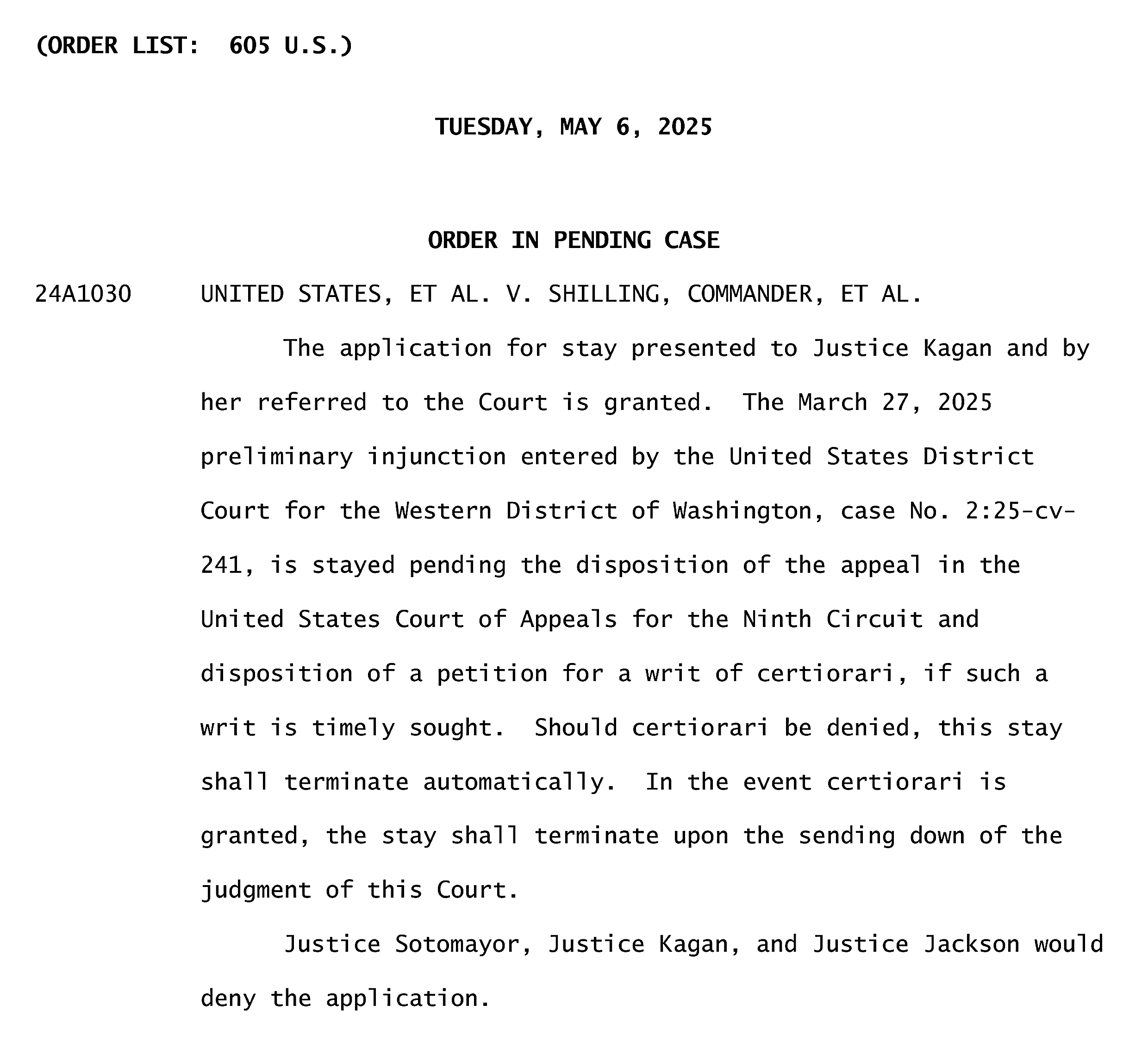

Nun ist dritte erwartete Entscheidung bereits da – und ausgesprochen kurz:

https://www.supremecourt.gov/orders/courtorders/050625zr_6j37.pdf (circa eine halbe Seite)

In dem Anfang für meine für heute (Dienstag) geplante, aber nicht fertig gewordene Fortsetzung hieß es zu dem transgender-Fall:

In dem Verfahren mit der No. 24A1030 geht es um Trumps Executive Order 14183 „Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness“ vom 27. Januar 2025, in der es einleitend u.a. heißt:

„Beyond the hormonal and surgical medical interventions involved, adoption of a gender identity inconsistent with an individual’s sex conflicts with a soldier’s commitment to an honorable, truthful, and disciplined lifestyle, even in one’s personal life. A man’s assertion that he is a woman, and his requirement that others honor this falsehood, is not consistent with the humility and selflessness required of a service member.“

(90 Fed. Reg. 8757 – 8759 [8757 <„Section 1. Purpose“>])

Konkret wird bestimmt:

„It is the policy of the United States Government to establish high standards for troop readiness, lethality, cohesion, honesty, humility, uniformity, and integrity. This policy is inconsistent with the medical, surgical, and mental health constraints on individuals with gender dysphoria. […]. Within 60 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of Defense (Secretary) shall update DoDI 6130.03 Volume 1 (Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction (May 6, 2018), Incorporating Change 5 of May 28, 2024) and DoDI 6130.03 Volume 2 (Medical Standards for Military Service: Retention (September 4, 2020), Incorporating Change 1 of June 6, 2022) to reflect the purpose and policy of this Order.“

(ebd., 8757 [„Sec. 2. Policy“ und „Sec. 4. Implementation“])

Die genannte Implementierung erfolgt anscheinend durch ein Memorandum for Senior Pentagon Leadership zu der zitierten Exekutivverordnung, das am 26. Februar vom amtierenden Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, Darin S. Selnick, unterzeichnet wurde1 (und nachfolgende Änderungen vom 4. März2), aber wohl in der Erwiderung auf den Regierungsantrag an den Supreme Court (vor allem) mit der Bezeichnung „effectuating guidance – the Hegseth Policy –“3 gemeint ist (Hegseth ist Trumps aktueller Verteidigungsminister).

Am 27. März erließ der District Court für den Western District des Bundesstaates Washington eine Preliminary Injunction (‚Eil-Rechtsschutz‘), nach der

„all defendants ARE PRELIMINARILY ENJOINED, pending further order of this Court, from implementing the Military Ban—Executive Order No. 14183. This includes the Hegseth Policy—‚Additional Guidance on Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness,‘ Dkt. 58-7, and all other memoranda, guidance, policies, or actions issued or forthcoming implementing the Military Ban or the Hegseth Policy.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.wawd.344431/gov.uscourts.wawd.344431.103.0_1.pdf, S. 1; Begründung: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.wawd.344431/gov.uscourts.wawd.344431.104.0_3.pdf)

Anträge4 der Regierung an den übergeordneten 9. Appeals Court, die Entscheidung des District Court vorläufig außer Vollzug zu setzen, blieben am 31.03. und am 18.04. erfolglos.

Darauf hin wandte sich die Regierung am 24. April an den Supreme Court. In ihrem Antrag argumentierte die Regierung u.a.:

„[…] this case does not plow new ground. In 2018, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis adopted a policy, materially indistinguishable from the one at issue here, that generally disqualified individuals with gender dysphoria from military service. Certain plaintiffs challenged the Mattis policy on equal protection and other grounds, and district courts enjoined the policy on a universal basis. This Court stayed those injunctions, see Trump v. Karnoski, 586 U.S. 1124 (2019); Trump v. Stockman, 586 U.S. 1124 (2019), and it should do the same here.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/24/24A1030/356382/20250424102154372_Emily_Shilling_et_al_application.pdf, S. 2 gedruckten bzw. 6 der digitalen Seitenzählung)

Die erstinstanzlichen KlägerInnen und AntragstellerInnen erwidern darauf:

„That this Court permitted a much narrower and different policy – the Mattis Policy – regarding transgender servicemembers to go into effect in 2019 does not change the calculus. See Trump v. Karnoski, 586 U.S. 1124 (2019). The instant Ban materially differs from the policy in that case. Under the Mattis Policy, no active duty servicemember who had already transitioned would be separated from service or have their healthcare denied. The Ban compels the expulsion of every transgender servicemember, including active-duty Respondents. Moreover, the Mattis Policy, as the Ninth Circuit found, relied on independent military judgment and did not heedlessly implement the 2017 proclamation that several courts had pointedly enjoined.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/24/24A1030/357948/20250501155514100_2025.05.01%20Shilling%20-%20Response%20in%20Opposition%20to%20Application%20for%20a%20Stay%20-%20Copy.pdf, S. 2 der gedruckten bzw. 14 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt5)

Und was die Supreme Court-Entscheidung von 2019 anbelangt, so argumentieren sie außerdem:

„the intervening years have provided evidence, based on transgender servicemembers’ actual experience, that such service is not contrary to ‚military effectiveness and lethality,‘ Gov’t Br. 26, but rather enhances military readiness, lethality, and unit cohesion. For these reasons, the stay decision in Karnoski does not control here and indeed counsels against the requested stay.“

(ebd., S. 3 bzw. 15; Hv. i.O.; FN hinzugefügt)

1 https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/24/24A1030/356382/20250424102154372_Emily_Shilling_et_al_application.pdf, S. 168 – 180 der Datei (Unterschrift auf S. 169; Anhang auf S. 170 – 180) = S. 124a – 136a der separaten Seitenzählung der Anlagen zum Regierungsantrags [oben in der Seitenmitte, unterhalb der Zeile in blauer Schrift]).

2 ebd., S. 223 – 224 bzw. 179a – 180a.

3 https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/24/24A1030/357948/20250501155514100_2025.05.01%20Shilling%20-%20Response%20in%20Opposition%20to%20Application%20for%20a%20Stay%20-%20Copy.pdf, S. 1 der gedruckten bzw. 13 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt: „A stay permitting implementation and enforcement of Executive Order 14183 (‚EO 14183‘), 90 Fed. Reg. 8757 (Jan. 27, 2025), and its effectuating guidance – the Hegseth Policy – (hereafter, collectively, the ‚Military Ban‘ or ‚the Ban‘) would upend the status quo by allowing the government to immediately begin discharging thousands of transgender servicemembers, including Respondents, thereby ending distinguished careers and gouging holes in military units. The Ban requires the Department of Defense (‚DoD‘) to ‚root out and separate every transgender service member – within 60 days,‘ App. 193a“. Im Regierungsantrag befindet sich auf S. 193a der Anlage (= S. 237 der Datei) S. 2 der Begründung der Entscheidung des District Court für den Western District des Bundesstaates Washington vom 27.03.2025. Dort wiederum heißt es in Zeile 4 u.a.: „Hegseth issued his Policy on February 26.“

4 Beide sind in einem Schriftsatz: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca9.afaa7f8c-a307-4e35-a174-cf2fa59424fe/gov.uscourts.ca9.afaa7f8c-a307-4e35-a174-cf2fa59424fe.9.0_1.pdf (Motion for immediate administrative stay by March 28 and stay pending appeal).

5 Zu „2017“ heißt es dort auf S. 5 bzw. 17: „On July 26, 2017, President Trump announced that ‚the United States Government will not accept or allow … Transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military.‘ Resp. App. 535a; App. 198a. One month later, he issued a Presidential Memorandum, entitled ‚Military Service by Transgender Individuals,‘ directing the DoD to maintain a freeze on accessions and prohibit access to gender-affirming health care, and ordering the Secretary to submit a plan barring transgender service. Resp. App. 305a–307a. The absolute ban announced in the 2017 Memorandum never took effect.“

6 „In February 2025, the Department of Defense adopted its current policy, which generally disqualifies from military service individuals who have gender dysphoria or have undergone medical interventions for gender dysphoria. The policy was based in part on the findings of a panel of experts convened during the first Trump Administration, which found that service by individuals with gender dysphoria was contrary to ‚military effectiveness and lethality.‘ App., infra, 8a.“ (https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/24/24A1030/356382/20250424102154372_Emily_Shilling_et_al_application.pdf, S. 1 f. bzw. 5 f.)

„the Department also finds that exempting such persons from well-established mental health, physical health, and sex-based standards, which apply to all Service members, including transgender Service members without gender dysphoria, could undermine readiness, disrupt unit cohesion, and impose an unreasonable burden on the military that is not conducive to military effectiveness and lethality“ (ebd., S. 8a bzw. 52).