.

Bisherige Berichterstattung zu dem Verfahren in Colorado

1. Wie berichtet, hatte der District Court Colorado am 14. April ‚Eil-Eil-Eil-Rechtsschutz‘ für die „Klasse“ der

„noncitizens in custody in the District of Colorado who were, are, or will be subject to the March 2025 Presidential Proclamation entitled Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of the United States by Tren de Aragua and/or its implementation“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69885285/dbu-v-trump/?filed_after=&filed_before=&entry_gte=&entry_lte=&order_by=desc#entry-14)

gewährt (die taz-Blogs vom 15.04.2024) und diesen dann am 22. April in ‚Eil-Eil-Rechtsschutz‘ (Temporary Restraining Order [TRO]) umgewandelt (siehe taz-Blogs vom selben Tage):

„Respondents shall not move Petitioners and members of the provisionally certified class outside the District of Colorado. Respondents shall provide a twenty-one (21) day notice to Petitioners and members of the provisionally certified class detained pursuant to the Act and Proclamation. Such notice must state the government intends to remove individuals pursuant to the Act and Proclamation. It must also provide notice of a right to seek judicial review, and inform individuals they may consult an attorney regarding their detainment and the government’s intent to remove them. Such notice must be written in a language the individual understands.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cod.243061/gov.uscourts.cod.243061.35.0_2.pdf, S. 34)

2. Wie ebenfalls berichtet, hat dann die Trump-Regierung bereits

„[e]inen Tag nach der zweiten der beiden genannten Entscheidungen […] beim District Court und […] noch einen Tag später beim übergeordneten 10. Appeals Court die Aussetzung der Entscheidungen beantragt. Der District Court hat den Antrag heute [Do., den 24.04.2024] abgelehnt;“

(taz-Blogs vom 24.04.2024)

3. Im Laufe der mitteleuropäischen Nacht von Samstag zu Sonntag ist nun die Erwiderung der Betroffenen auf den von der Trump-Regierung an den Appeals Court gerichteten Aussetzungsantrag eingegangen:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.24.0.pdf (24 Seiten)

und in der mitteleuropäischen Nacht von Sonntag zu Montag die Rück-Antwort der Regierung:https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.25.0.pdf (14 Seiten).

Der stay-Antrag der Regierung vom 24. April

4. Vergegenwärtigen wir uns aber zunächst noch einmal den stay-Antrag der Regierung vom 24. April (Donnerstag vergangener Woche); dieser war gegelidert in

-

vier (un-numerierte) Teile Introduction, Background, Argument und Conclusion,

-

wobei der Teil Argument seinerseits in die Abschnitte „I. The District Court’s Injunctive Orders are Appealable“, „II. The Government Has a Strong Likelihood of Success on Appeal“ und „III. The Other Stay Factors Support Issuance of a Stay“ gegliedert war.

-

Von diesen war der Abschnitt II. wiederum in die Unterabschnitte „A. The District Court Erred in Issuing the TRO Because It Lacked Jurisdiction over the Case“ und „B. Plaintiffs’ Facial Challenges To The AEA Proclamation Fail“ gegliedert.

Um mit ihrem ganzen Antrag erfolgreich zu sein, muß die Regierung

-

(1.) mit ihrer These aus Abschnitt „I. The District Court’s Injunctive Orders are Appealable“ erfolgreich sein

-

außerdem (2.) mit zumindest einer ihrer beiden Thesen den Unterabschnitten II. A. und B.

-

Schließlich müssen auch noch die „Other Stay Factors“ aus Abschnitt III. eher für die Regierung als für die Betroffenen sprechen.

und

5. a) Lassen wir im folgenden – der Einfachheit halber – die Frage beiseite, ob die fragliche TRO überhaupt anfechtbar ist. (Grundsätzlich sind TRO nicht anfechtbar, ausnahmsweise aber schon – und mir scheint, es gibt eine gewisse opportunistische Tendenz, daß die Seite, die von der jeweiligen TRO begünstigt ist, schnell mit der These bei der Hand ist, daß kein Ausnahmefall vorliege; und die Seite, die von der jeweiligen TRO belastet ist, genauso schnell mit der These bei der Hand ist, daß sehr wohl ein Ausnahmefall vorliege – also Anfechtbarkeit gegeben sei.)

b) Lassen wir – zur weiteren Vereinfachung – die „Other Stay Factors“ auch noch beiseite, so können wir uns dann also auf Unterabschnitte „A. The District Court Erred in Issuing the TRO Because It Lacked Jurisdiction over the Case“ und „B. Plaintiffs’ Facial Challenges To The AEA Proclamation Fail“ aus Teil „II. The Government Has a Strong Likelihood of Success on Appeal“ konzentrieren.

6. a) Ich werde in Abschnitt 10. noch kurz erläutern, warum ich eher davon ausgehe, daß die Plaintiffs mit ihren „Challenges To The AEA Proclamation“ Erfolg haben werden – die Regierung mit ihrer „Fail“-These also nicht.

b) Wir können uns daher also zunächst einmal auf den Unterabschnitte „A. The District Court Erred in Issuing the TRO Because It Lacked Jurisdiction over the Case“ konzentrieren.

7. Die Regierung hatte dort folgendermaßen argumentiert:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.3.0.pdf (22 Seiten + 26 Seiten Anlagen)

Die Erwiderung der Betroffenen

8. Sehen wir uns nun die Antwort der Betroffenen zu diesem Thema an:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.24.0.pdf (24 Seiten)

Vergleich der Argumente wg. „Lacked Jurisdiction over the Case“

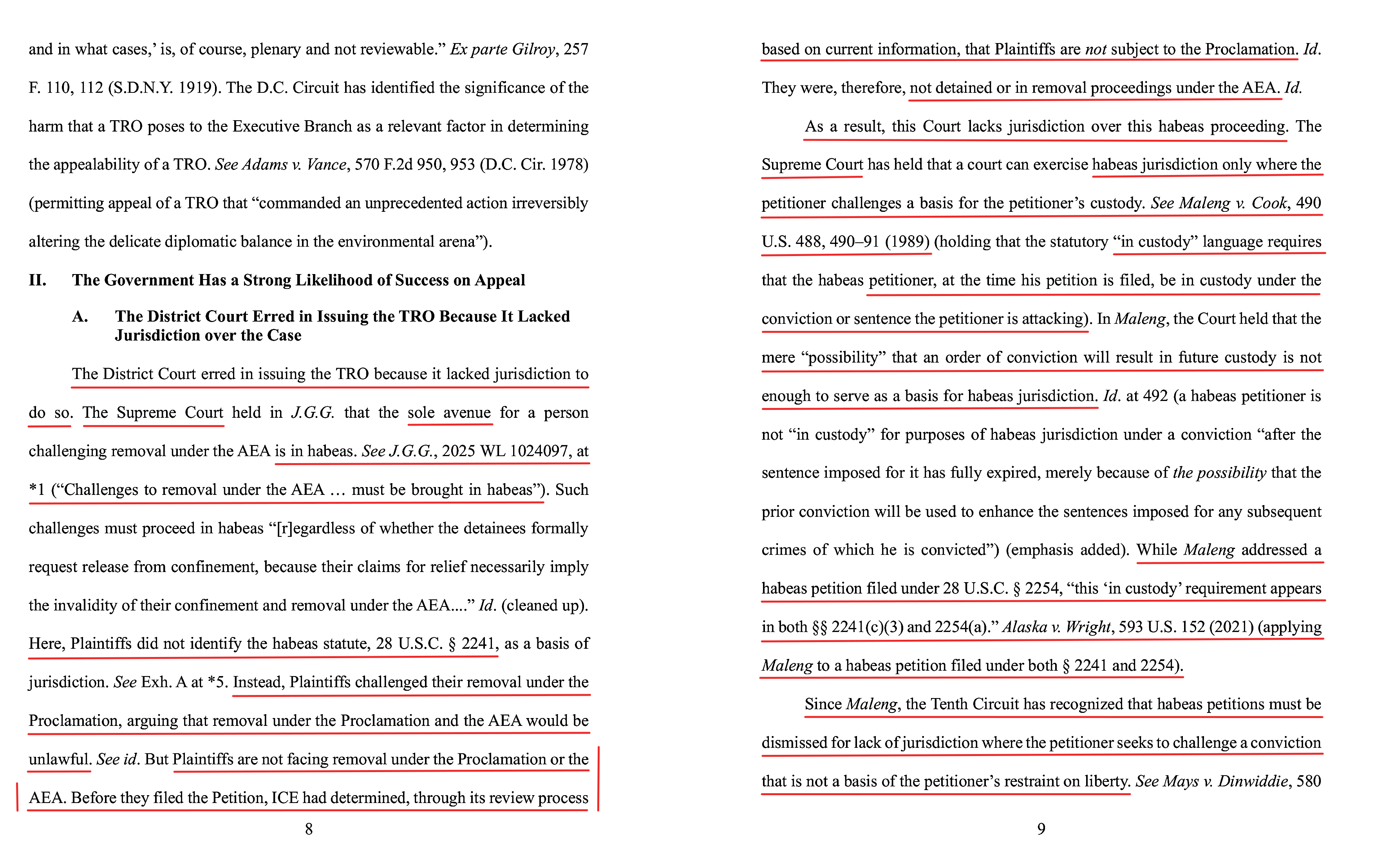

9. a) aa) Die Regierung sagt also zunächst:

„The Supreme Court held in J.G.G. that the sole avenue for a person challenging removal under the AEA is in habeas. See J.G.G., 2025 WL 1024097, at *1 (‚Challenges to removal under the AEA … must be brought in habeas‘). Such challenges must proceed in habeas ‚[r]egardless of whether the detainees formally request release from confinement, because their claims for relief necessarily imply the invalidity of their confinement and removal under the AEA….‘ Id. (cleaned up). Here, Plaintiffs did not identify the habeas statute, 28 U.S.C. § 2241, as a basis of jurisdiction. See Exh. A at *5.“

J.G.G., 2025 WL 1024097, at *1 ist: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a931_2c83.pdf, S. 2.

28 U.S.C. § 2241 ist das: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title28-section2241&num=0&edition=prelim.

Exh. A at *5 ist Seite 5 von Anhang A zu dem stay-Antrag der Regierung – also: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.3.0.pdf, S. 32.

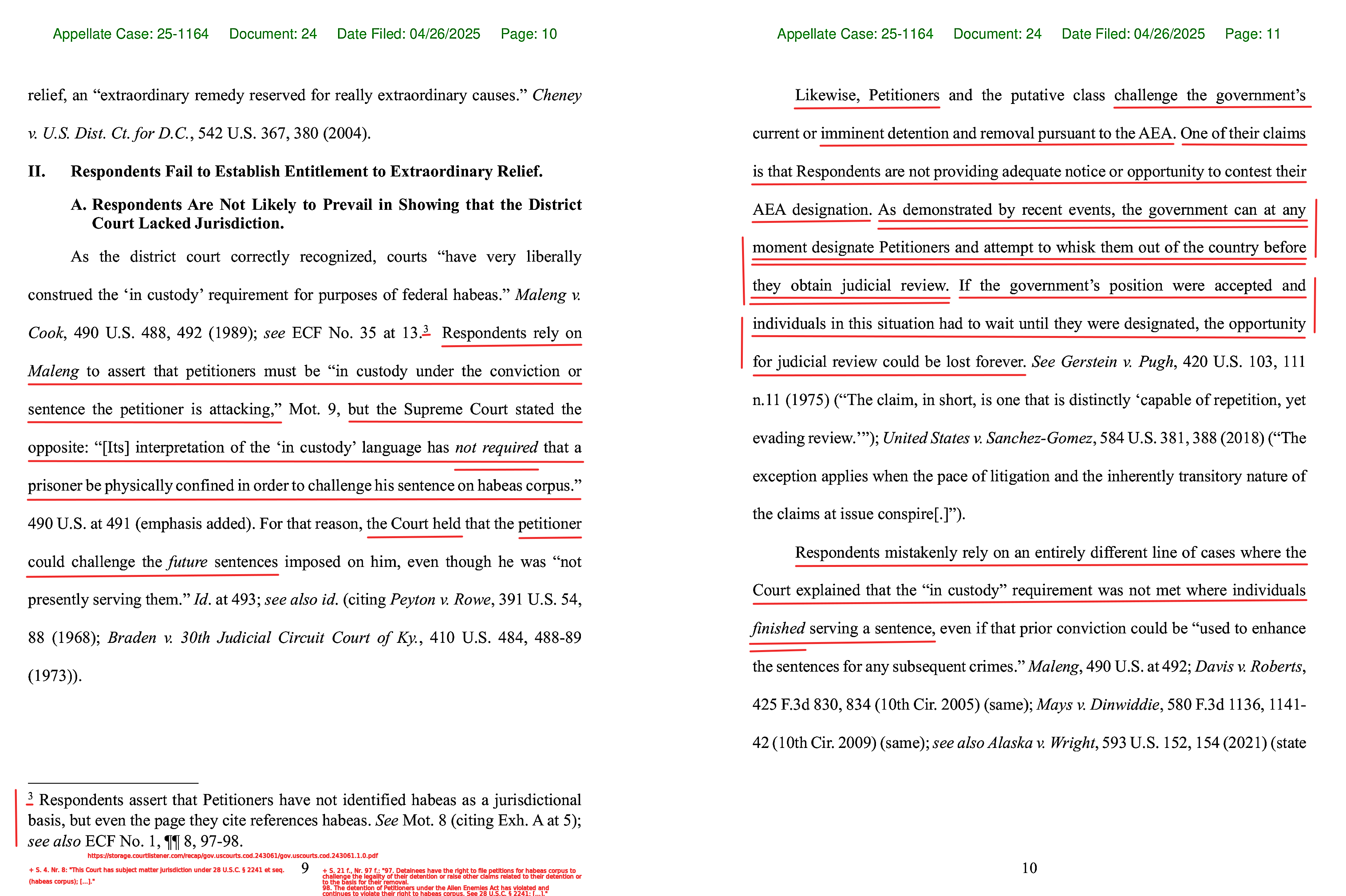

bb) Darauf antworten die Betroffenen:

„Respondents assert that Petitioners have not identified habeas as a jurisdictional basis, but even the page they cite references habeas. See Mot. 8 (citing Exh. A at 5); see also ECF No. 1, ¶¶ 8, 97-98.“

Exh. A ist gar kein Schriftsatz der Betroffenen, sondern die von der Trump-Regierung angefochteten Entscheidung des District Court. Dort heißt es auf S. 5 in der linken Spalte unten (vor der Zwischenüberschrift): „Petitioners have satisfied the habeas ‚in custody‘ jurisdictional requirement. See 28 U.S.C. § 2241.“ (Hv. hinzugefügt) Auch in der rechten Spalte oben ist noch einmal die von der Regierung (als angeblich nicht erwähnt) in Bezug genommene Norm 28 U.S.C. § 2241 sehr wohl erwähnt.

Und in dem erstinstanzlichen complaint der Betroffenen (ECF No. 1) heißt es sehr wohl

-

auf S. 21 f. (bei Nr. 97 und 98):

-

auf S. 4 (bei Nr. 8):

„97. Detainees have the right to file petitions for habeas corpus to challenge the legality of their detention or raise other claims related to their detention or to the basis for their removal.

98. The detention of Petitioners under the Alien Enemies Act has violated and continues to violate their right to habeas corpus. See 28 U.S.C. § 2241; U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 2 (Suspension Clause).“

und

„8. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 2241 et seq. (habeas corpus); […].“

b) aa) Die Regierung sagt sodann:

„Plaintiffs challenged their removal […]. But Plaintiffs are not facing removal under the Proclamation or the AEA. Before they filed the Petition, ICE had determined, through its review process based on current information, that Plaintiffs are not subject to the Proclamation. Id. [Exh. A at *5] They were, therefore, not detained or in removal proceedings under the AEA. Id. As a result, this Court lacks jurisdiction over this habeas proceeding. The Supreme Court has held that a court can exercise habeas jurisdiction only where the petitioner challenges a basis for the petitioner’s custody. See Maleng v. Cook, 490 U.S. 488, 490–91 (1989) (holding that the statutory ‚in custody‘ language requires that the habeas petitioner, at the time his petition is filed, be in custody under the conviction or sentence the petitioner is attacking). In Maleng, the Court held that the mere ‚possibility‘ that an order of conviction will result in future custody is not enough to serve as a basis for habeas jurisdiction. Id. at 492 (a habeas petitioner is not ‚in custody‘ for purposes of habeas jurisdiction under a conviction ‚after the sentence imposed for it has fully expired, merely because of the possibility that the prior conviction will be used to enhance the sentences imposed for any subsequent crimes of which he is convicted‘) (emphasis added).“

„Before they filed the Petition, ICE had determined, through its review process based on current information, that Plaintiffs are not subject to the Proclamation. Id.“ soll sich wohl auf folgende Passage in der Entscheidung des District Court beziehen:

„it is undisputed that D.B.U. and R.M.M. are not ‚currently‘ — in the words of counsel — civilly detained pursuant to the Act and Proclamation. See, e.g., ECF No. 2-1 at 2 ¶ 8; ECF No. 2-2 at 2 ¶ 11. But, taking Respondents at their word from oral argument, and certainly from the TRO record, there is no definite evidence ICE will conclude or has concluded Petitioners do not fall under the Proclamation’s ambit, and are instead subject only to Title 8’s immigration removal procedures.“ (Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Die Supreme Court-Entscheidung Maleng v. Cook, 490 U.S. 488 (1989) gibt es dort: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep490/usrep490488/usrep490488.pdf.

Auf S. 490–91 heißt es: „In 1985, while in federal prison, respondent filed a pro se petition for habeas corpus relief in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington. […]. The District Court dismissed the petition for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction, holding that respondent was not ‚in custody‘ for the purposes of a habeas attack on the 1958 conviction because the sentence imposed for that conviction had already expired. […]. The Court of Appeals held that respondent was still ‚in custody‘ under the 1958 conviction, even though the sentence imposed for that conviction had expired, because it had been used to enhance the sentences imposed in 1978 for his 1976 state convictions, which he had yet to serve. […]. We granted certiorari to review this interpretation of the ‚in custody‘ requirement. […]. The federal habeas statute gives the United States district courts jurisdiction to entertain petitions for habeas relief only from persons who are ‚in custody in violation of the Constitution or laws or treaties of the United States.'“ (Hv. i.O.)

Auf S. 492 heißt es: „The question presented by this case is whether a habeas petitioner remains ‚in custody“ under a conviction after the sentence imposed for it has fully expired, merely because of the possibility that the prior conviction will be used to enhance the sentences imposed for any subsequent crimes of which he is convicted. We hold that he does not.“

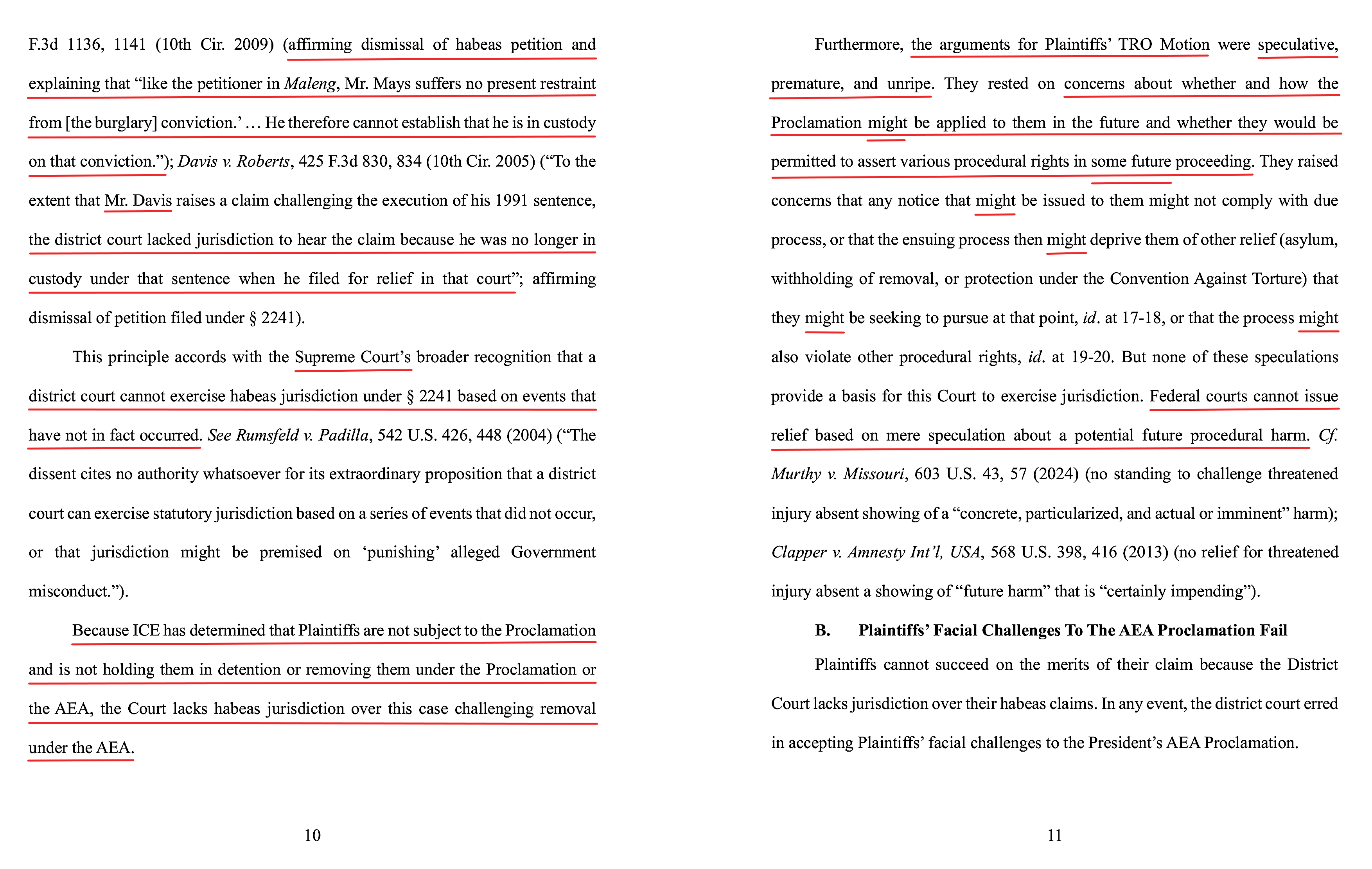

bb) Die Betroffenen erwidern darauf:

„Respondents rely on Maleng to assert that petitioners must be ‚in custody under the conviction or sentence the petitioner is attacking,‘ Mot. 9, but the Supreme Court stated the opposite: ‚[Its] interpretation of the ‘in custody’ language has not required that a prisoner be physically confined in order to challenge his sentence on habeas corpus.‘ 490 U.S. at 491 (emphasis added). For that reason, the Court held that the petitioner could challenge the future sentences imposed on him, even though he was ’not presently serving them.‘ Id. at 493″ (Hv. i.O.)

Mot. 9 ist Seite 9 des stay-Antrages der Regierung.

490 U.S. at 491 ist S. 491 der Maleng-Entscheidung und Id. at 493 ist dort S. 493.

In der Tat heißt es in der Maleng-Entscheidung auf S. 491 – neben dem schon Zitierten auch: „Our interpretation of the ‚in custody‘ language has not required that a prisoner be physically confined in order to challenge his sentence on habeas corpus. In Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U. S. 236 (1963), for example, we held that a prisoner who had been placed on parole was still ‚in custody‘ under his unexpired sentence. […], see also Hensley v. Municipal Court, San Jose-Milpitas Judicial Dist., Santa Clara County, 411 U. S. 345 (1973); Braden v. 30th Judicial Circuit Court of Ky., 410 U. S. 484 (1973).“

Und auf S. 493 der Maleng-Entscheidung heißt es: „We do think […] that respondent may challenge the sentences imposed upon him by the State of Washington in 1978, even though he is not presently serving them. […]. In Peyton v. Rowe, 391 U. S. 54 (1968), we […] held that a petitioner who was serving two consecutive sentences imposed by the Commonwealth of Virginia could challenge the second sentence which he had not yet begun to serve.“

c) aa) Des weiteren sagt die Regierung:

„This principle [Die Regierungs-Lesart der Maleng-Entscheidung] accords with the Supreme Court’s broader recognition that a district court cannot exercise habeas jurisdiction under § 2241 based on events that have not in fact occurred. See Rumsfeld v. Padilla, 542 U.S. 426, 448 (2004) (“The dissent cites no authority whatsoever for its extraordinary proposition that a district court can exercise statutory jurisdiction based on a series of events that did not occur, or that jurisdiction might be premised on ‘punishing’ alleged Government misconduct.”).“

Die Supreme Court-Entscheidung Rumsfeld v. Padilla, 542 U.S. 426 (2004) gibt es dort: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep542/usrep542426/usrep542426.pdf; das von der Regierung angeführte Zitat befindet sich tatsächlich auf S. 448.

bb) Die Betroffenen antworten darauf:

„Respondents rely on Rumsfeld v. Padilla, but there, the Court rejected the ‚extraordinary proposition‘ that habeas jurisdiction could be exercised on the theory that the petition could have been filed earlier in the district court, even though the petitioner was not in the district at the time of filing. 542 U.S. 426, 448 (2004). That speaks nothing to imminent harm or detention.“ (Hv. i.O.)

Die Betroffenen nehmen also eine Unterscheidung vor zwischen einer rückblickenden hypothetischen Betrachtungsweise („could have been filed earlier“), die allein die damalige Supreme Court-Mehrheit zurückgewiesen habe, und einer in die Zukunft gerichteten Betrachtungsweise („imminent harm or detention“), um die es damals nicht gegangen sei.

d) aa) Schließlich sagt die Regierung:

„the arguments for Plaintiffs’ TRO Motion were speculative, premature, and unripe. They rested on concerns about whether and how the Proclamation might be applied to them in the future and whether they would be permitted to assert various procedural rights in some future proceeding. They raised concerns that any notice that might be issued to them might not comply with due process, [… usw.]“ (Hv. hinzugefügt)

bb) Die Betroffenen antworten darauf:

„The government’s arguments are ultimately about standing, contending that Petitioners’ claims are ’speculative‘ and ‚unripe,‘ […] but Petitioners have established a ’substantial risk the threatened harm will occur‘ — that, absent relief, they will be designated and summarily removed under the Proclamation. […]. The government has issued both Petitioners I-213 Forms alleging they are members of or affiliated with TdA, and it has reiterated those claims in immigration court. […]. The Proclamation applies to all alleged TdA members and the government’s criteria for designating individuals is notoriously permissive. While the government states that it has not currently designated Petitioners under the AEA […], it has not foreclosed the possibility for the future, […], nor even provided reassurances that it would not remove them pending this litigation, in contrast to other cases. […]. And its recent actions in Texas [das bezieht sich auf die Ereignisse am Karfreitag diesen Jahres und die anschließend Entscheidung der Supreme Court am Karsamstag, den 19.04. um 1:00 Uhr] show that any implicit or assumed assurances are not sufficient. Under these circumstances, Petitioners have shown far more than the ’substantial risk‘ of injury required. Respondents’ argument that notice is sufficient is wholly circular as it would mean no one would have an opportunity to access the courts because they are either too early and without injury, or too late and the government has no ability to rectify their wrongful removal.“ (Hv. i.O.)

Die „Challenges To The AEA Proclamation“

10. Kommen wir nun zu der Regierungs-These „Plaintiffs’ Facial Challenges To The AEA Proclamation Fail“. Um mit der These Erfolg zu haben, müßte die Regierung (in etwa) darlegen, daß es ihr im späteren Hauptsacheverfahren wahrscheinlich gelingen wird, zu beweisen, daß Folgendes gegeben ist:

„a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government“

(50 USC 21 Satz 1).

a) Daß gerade ein erklärter Krieg zwischen den USA und Tren de Aragua (oder Venezuela) stattfinde, behauptet die Trump-Regierung selbst nicht.

b) Sie behauptet aber, daß eine „invasion or predatory incursion“ durch Tren de Aragua in die USA stattfinde. Selbst wenn wir zugestehen, daß in irgendeinem weiten, metaphorischen Sinne illegale Einwanderung und anschließendes Begehen von (weiteren) Straftaten vielleicht als „invasion or predatory incursion“ bezeichnet werden kann, so müssen die beiden zuletzten genannten Ausdrücke aber in ihrem konkreten Kontext interpretiert werden:

aa) Es muß sich um etwas Handeln, das von einer „foreign nation or government“ ausgeht. (Jedenfalls in der Regel wird illegale Einwanderung aber nicht von Regierungen, sondern von Individuen – und vielleicht noch von Netzwerken, die die Individuen unterstützen – betrieben.)

bb) Es muß ähnliches wie – und nicht etwas ganz anderes als – declared war sein. (Illegale Einwanderung ist – auch, wenn ihr [weitere] Straftaten nachfolgen – aber kein ‚kleiner Krieg‘, sondern etwas anderes als ein Krieg.)

cc) 50 USC 21 steht in „Title 50 – War and National Defense“ des US Code (und nicht in „Title 8 – Aliens and Nationality“).

Die ersten beiden dieser Argumente sowie weitere Argumente hatte auch schon (die von Ronald Reagan 1986 als District Court– und von George H.W. Bush 1990 als Appeal Court-Richterin für Washington, D.C. nominierte) Karen LeCraft Henderson vorgebracht (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cadc.41845/gov.uscourts.cadc.41845.01208724047.0_2.pdf, S. 17 Mitte bis 24 oben der Datei bzw. S. 16 Mitte bzw. 23 oben der gedruckten, separate Seitenzählung des Henderson-Votums).

c) Die Begriffe „foreign nation“ und „government“ sind nicht nur für die Auslegung der Begriffe „invasion“ und „predatory incursion“ relevant, sondern auch selbst Bezeichnungen für (zwei zueinander alternative) Tatbestandsvoraussetzungen.

aa) Die Trump-Regierung behauptet aber vorrangig bloß, daß Tren de Aragua „directly and at the direction, clandestine or otherwise, of the Maduro regime in Venezuela“ handele. Allein dadurch ist Tren de Aragua aber noch keine Regierung oder Nation. (Und daß Venezuela die USA angreife, behauptet auch die Trump-Regierung – trotz ihrer ‚Steuerungs-These‘ – nicht; die Proklamation zielt – jedenfalls nach ihrem Wortlaut – auch nicht auf venezolanischen StaatsbürgerInnen im allgemeinen, sondern auf angebliche TdA-Mitglieder.)

bb) Nur nebenbei wird in der TdA-Prokolamation auch noch behauptet, „Venezuelan national and local authorities have ceded ever-greater control over their territories to transnational criminal organizations, including TdA“. Daran anknüpfend heißt es in dem stay-Antrag der Regierung: „In those areas where it is operating, TdA is in fact operating as a criminal state, independent or in place of the normal civil society and government.“ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.3.0.pdf, S. 16 f. der gedruckten bzw. 18 f. der digitalen Seitenzählung).

Aber die US-Regierung behauptet nicht, daß Tren de Argua citizens u.ä. [*] habe, sondern spricht – insofern vermutlich zutreffend – von members. Tren de Argua gibt weder Pässe noch eine Währung noch ein Gesetz- und Verordnungblatt aus (auch wenn Tren de Aragua gewisse Regeln haben mag und sich gegen konkurrierende Kräfte durchzusetzen versuchen mag).

d) Schließlich scheint mir der Eifer, mit dem die US-Regierung versucht, gerichtliche Kontrolle zu vermeiden und die Leute möglichst in Nacht- und Nebel-Aktionen abzuschieben, darauf hinzudeuten, daß sie selbst nicht sonderlich optimistisch ist, was den eventuellen Erfolg ihrer Argumente vor Gericht (bzgl. Auslegung des Alien Enemies Act) anbelangt.

Die Rück-Antwort der Regierung aus der Nacht von Sonntag zu Montag

Abschnitt II.

11. a) Die Rück-Antwort der Regierung auf die Erwiderung der Betroffenen ging kurz nach Mitternacht der Nacht von Sonntag zu Montag (MESZ) ein. Dort trägt Abschnitt II. des Teils Argument die Überschrift Petitioners Identify No Jurisprudence Justifying Expansion of Jurisdiction to Include Speculative Habeas Cases und lautet folgendermaßen:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.25.0.pdf

b) Ihren – von den Betroffenen widerlegten [siehe oben 9. a) bb)] – Vorwurf,

„Plaintiffs did not identify the habeas statute, 28 U.S.C. § 2241, as a basis of jurisdiction.“

wiederholt die Regierung also nicht.

c) aa) Aber sie sagt unter anderem:

„As the government explained previously, there is no jurisdiction over this case because Petitioners are not in detention pursuant to the AEA, they will receive notice if they are placed in AEA detention, and their claims are therefore entirely speculative. It is a basic principle of Article III that speculation of this type cannot give rise to the sort of injury in fact that allows a federal court to weigh in, because injury here is not ‚certainly impending.‘ Clapper v. Amnesty Intern. USA, 568 U.S. 398, 409 (2013) (‚Allegations of possible future injury are not sufficient‘) (emphasis in original).“

Die Supreme Court-Entscheidung Clapper v. Amnesty Intern. USA, 568 U.S. 398 (2013) gibt es dort: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep568/usrep568398/usrep568398.pdf.

Auf S. 409 heißt es: „To establish Article III standing, an injury must be ‚concrete, particularized, and actual or imminent; fairly traceable to the challenged action; and redressable by a favorable ruling.‘ Monsanto Co. v. Geertson Seed Farms, 561 U. S. 139, 149 (2010); see also Summers, supra, at 493; Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U. S., at 560–561. ‚Although imminence is concededly a somewhat elastic concept, it cannot be stretched beyond its purpose, which is to ensure that the alleged injury is not too speculative for Article III pur poses—that the injury is certainly impending.” Id., at 565, n. 2 (internal quotation marks omitted). Thus, we have repeatedly reiterated that ‚threatened injury must be certainly impending to constitute injury in fact,‘ and that ‚[a]llegations of possible future injury‘ are not sufficient. Whitmore, 495 U. S., at 158 (emphasis added; internal quotation marks omitted); see also Defenders of Wildlife, supra, at 565, n. 2, 567, n. 3; see DaimlerChrysler Corp., supra, at 345; Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services (TOC), Inc., 528 U. S. 167, 190 (2000); Babbitt v. Farm Workers, 442 U. S. 289, 298 (1979).“

bb) Das von der Regierung angeführte Zitat ist also korrekt. Allerdings ist auch gar nicht strittig, daß bloß spekulative Schäden für die Klagebefugnis nicht ausreichen.

Die Regierung sagt (zwar): „they [die Betroffenen] will receive notice if they are placed in AEA detention“; aber strittig ist, ob sie die etwaige Benachrichtigung ggf. rechtzeitig erhalten werden bzw. was „rechtzeitig“ genau bedeutet. Der Streitpunkt ist, daß die Regierung den Betroffenen nur 12 Stunden Zeit geben will, um auf eine etwaige Benachrichtigung zu reagieren (siehe dazu unten) genauer.

Die controvery (Artikel III Absatz 2 der US-Verfassung: „The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases […]; – to Controversies to which the United States will be a party […]“),

-

ob die Regierung eine Frist von mehr als 12 Stunden gewähren muß, um auf die eine etwaige Benachrichtigung mit der Ankündigung der Einlegung eines Rechtsbehelfs reagieren zu können;

-

ob es ausreicht, wenn die Benachrichtigung den Betroffenen schriftlich auf Englisch gegeben wird oder ob sie auch auf Kastilisch („Spanisch“) sein muß und/oder auch den AnwältInnen zugesandt werden muß

-

ob in der Benachrichtigung – inbesondere (noch) nicht anwaltlich vertretenen Betroffenen – erklärt werden muß, daß und wie sie einen Rechtsbehelf einlegen können,

und

ist nicht bloß spekulativ, sondern schon gegenwärtig. Und die Behauptung der Regierung, die AntragstellerInnen seien TdA-Mitglieder ist auch schon gegenwärtig; zur Anwendung der Tren de Aragua-Proklamation auf die Antragsteller ist es also nur noch ein kleiner Schritt (zu diesem – von der Regierung geltend gemachten – kleinen Unterschied siehe sogleich).

d) Außerdem schreibt die Regierung in ihrer Rück-Antwort unter anderem:

„Petitioners dispute the government’s reliance on Maleng v. Cook, 490 U.S. 488 (1989)—a case which held that the district court lacked jurisdiction to consider a habeas challenge after the sentence imposed had expired, even if the prior conviction would be used to enhance sentences imposed for subsequent crimes. […]. Indeed, Maleng clarified that jurisdiction did not extend to previous periods of detention, the point relied on by Petitioners. Maleng, 490 U.S. at 490–91. However, Petitioners ignore the second aspect of Maleng: Maleng believed that his prior sentence could affect any future period of detention, and the Supreme Court held this was too speculative to confer jurisdiction. See id.“ (kurisve Hv. i.O.; fette hinzugefügt)

Die online-Fundstelle für die Supreme Court-Entscheidung Maleng v. Cook, 490 U.S. 488 (1989) war oben bereits genannt – es handelt sich um folgende Adresse: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep490/usrep490488/usrep490488.pdf.

e) Des weiteren sagt die Regierung:

„Here, contrary to Petitioners’ claim there is a ’substantial risk‘ that detention under the AEA is ‚imminent,‘ Resp. 10–12, there is no evidence that the government intends to detain either Petitioner under the AEA. Petitioners have not been designated as ‚Alien Enemies.‘ ECF 35 at 5-9; Resp. 11-12. Petitioners stated that they were ‚issued‘ I-213 forms ‚alleging that they are members of or affiliated with [Tren de Aragua (‚TdA‘)].‘ Resp. 11. But the I-213 form is not an AEA determination of notice. It is internal government documentation […]. Thus, Petitioners have not been notified under the AEA or ‚accused‘ of TdA membership, as they claim. This record is insufficient to establish ’sufficient risk of ›being designated‹ as TdA members‘ under the AEA as the district court found when issuing the TRO.“

Das mag alles sein – aber es bleibt unklar ist, was nach Regierungsansicht noch passieren müßte, damit sie die „internal government documentation“ um eine „AEA determination of notice“ ergänzt. Und es ist schon jetzt strittig, wieviel Zeit die Regierung zwischen der etwaige notice und der Vollziehung einer Abschiebung lassen müßte.

Resp. 10–12 ist Seite 10 – 12 der Erwiderung der Betroffenen aus der Nacht von Samstag zu Sonntag.

Die I-213 forms sind mir noch nicht untergekommen; vielleicht sind sie aber trotzdem schon irgendwo online.

ECF 35 at 5-9 ist Seite 5 bis 9 der District Court-Entscheidung, die Regierung außer Vollzug gesetzt wissen will.

Resp. 11-12 ist Seite 11 – 12 der Erwiderung der Betroffenen.

Und Resp. 11 ist Seite 11 der Erwiderung.

Abschnitt IV.

f) aa) Weiter unten in der Rück-Antwort der Regierung gibt es außerdem einen Abschnitt „IV. The Government’s Notice Procedure Satisfies Due Process“:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040/gov.uscourts.ca10.90040.25.0.pdf

bb)

Ludecke, 335 U.S. at 162–63 ist: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep335/usrep335160/usrep335160.pdf, S. 3 und 4 der Datei. Worum es in der Ludecke-Entscheidung ging, hatte ich dort: https://blogs.taz.de/theorie-praxis/files/2025/03/Supreme_Court-Schrifsatz_Trump-Reg_AEA_TdA.pdf, S. 16 – 21 erklärt.

Die Supreme Court-Entscheidung DHS v. Thuraissigiam, 591 U.S. 103 (2020) gibt es dort: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/591us1r48_9o6b.pdf. Auf S. 139 (= 38 der Datei) heißt es – als Zitat aus einer älteren Entscheidung -: „Whatever the procedure authorized by Congress is, it is due process as far as an alien denied entry is concerned.“

ECF 44, Cisneros Declaration ¶ 4, 9 ist: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cod.243061/gov.uscourts.cod.243061.44.1.pdf, S. 3, Nr. 4 und 9. AEA-21B ist dort im Anhang zu der Erklärung auf S. 6 der Datei.

Die beiden Entscheidungen Manyary v. Bondi, 129 F.4th 473 (8th Cir. 2025) und Platero-Rosales v. Garland, 55 F.4th 974 habe ich bisher nicht finden können.

Die Entscheidung Khan v. Ashcroft, 374 F.3d 825 (9th Cir. 2004) gibt es dort: https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/786870/jamal-khan-v-john-ashcroft-attorney-general/. In der Entscheidung heißt es in Abschnitt II. (Discussion) A. (Notice): „Khan concedes that both the first and second notice contained all of the elements required by statute, and that neither IIRIRA nor its implementing regulations require that the INS provide those notices in any language other than English.“

ECF 44, Cisneros Declaration ¶ 10 sowie Id. ¶ 11, 12 sind: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cod.243061/gov.uscourts.cod.243061.44.1.pdf, S. 4, Nr. 10, 11 und 12.

Die Dokumente zum Verfahren Las Americas v. Noem, No. 25-418 gibt es dort: https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69633721/las-americas-immigrant-advocacy-center-v-noem/, aber das Oral Ruling Tr[anscript] finde ich nicht.

Die Entscheidung Adams v. Vance, 570 F.2d 950 gibt es dort: https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/353165/jacob-adams-v-cyrus-vance-secretary-of-state/. Dort heißt es bei Textziffer 14: „The District Court treated this application for immediate injunctive relief as an ordinary one. Yet when requested immediate injunctive relief deeply intrudes into the core concerns of the executive branch, a court is ‚quite wrong in routinely applying to this case the traditional standards governing more orthodox ›stays‹.'“ Das Wort „wartime“ findet sich dagegen nicht in der Entscheidung. Es scheint sich also auf den AEA zu beziehen – und die Trump-Regierung gesteht (anscheinend) zu, daß der AEA ein Gesetz für Kriegszeiten ist…

8 U.S.C. § 1225 gibt es dort: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title8-section1225&num=0&edition=prelim. Und (b)(1)(B) I bis III lauten:

„(B) Asylum interviews

(i) Conduct by asylum officers

An asylum officer shall conduct interviews of aliens referred under subparagraph (A)(ii), either at a port of entry or at such other place designated by the Attorney General.

(ii) Referral of certain aliens

If the officer determines at the time of the interview that an alien has a credible fear of persecution (within the meaning of clause (v)), the alien shall be detained for further consideration of the application for asylum.

(iii) Removal without further review if no credible fear of persecution

(I) In general

Subject to subclause (III), if the officer determines that an alien does not have a credible fear of persecution, the officer shall order the alien removed from the United States without further hearing or review.

(II) Record of determination

The officer shall prepare a written record of a determination under subclause (I). Such record shall include a summary of the material facts as stated by the applicant, such additional facts (if any) relied upon by the officer, and the officer’s analysis of why, in the light of such facts, the alien has not established a credible fear of persecution. A copy of the officer’s interview notes shall be attached to the written summary.

(III) Review of determination

The Attorney General shall provide by regulation and upon the alien’s request for prompt review by an immigration judge of a determination under subclause (I) that the alien does not have a credible fear of persecution. Such review shall include an opportunity for the alien to be heard and questioned by the immigration judge, either in person or by telephonic or video connection. Review shall be concluded as expeditiously as possible, to the maximum extent practicable within 24 hours, but in no case later than 7 days after the date of the determination under subclause (I).

(IV) Mandatory detention

Any alien subject to the procedures under this clause shall be detained pending a final determination of credible fear of persecution and, if found not to have such a fear, until removed.“

(Hv. hinzugefügt; Original-Hv. getilgt

Der Betroffenen hatten sich auf S. 15 der gedruckten bzw. S. 16 der digitalen Seitenzählung ihrer Erwiderung zu der gerade zitierten Norm geäußert:

Im Haupttext der Erwiderung heißt es unmittelbar nach Fußnote 5: „In short, 12 hours would be unreasonable under any circumstances but it is especially unreasonable here given the nature of the class and the consequences of ending up in a Salvadoran prison for the rest of their lives.“

Die Fundstelle Thuraissigiam, 591 U.S. at 139 war bereits weiter oben verlinkt und zitiert.

Zur Entscheidung Sanchez Puentes v. Garite, 3:25-cv-00127-DB, 2025 WL 1203179 (W.D. Tex. Apr. 25, 2025) siehe meinen Artikel vom 26.04.2025.

Nun zu den in der Rück-Antwort auf S. 10 oben aufgelisteten Verfahren:

+ G.F.F. & J.G.O. v. Trump, No. 25-cv-2886 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 8, 2025)

https://courtlistener.com/docket/69857769/gff-v-trump/

+ J.A.V. v. Trump, No. 25-cv-72 (S.D. Tex. Apr. 8, 2025)

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69862833/jav-v-trump/

+ A.S.R. v. Trump, No. 25-cv-133 (W.D. Pa. Apr. 15, 2025)

https://courtlistener.com/docket/69893393/asr-v-trump/.

+ Viloria-Aviles v. Trump, No. 25-cv-611 (D. Nev. Apr. 3, 2025)

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69843017/viloria-aviles-v-trump/.

+ A.A.R.P. v. Trump, No. 25-cv-59 (N.D. Tex. Apr. 16, 2025)

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69898198/aarp-v-trump/.

+ Gutierrez-Contreras v. Trump, No. 25-cv-911 (C.D. Cal. Apr. 14, 2025)

https://courtlistener.com/docket/69891354/yostin-sleiker-gutierrez-contreras-v-warden-desert-view-annex/.

+ Quintanilla Portillo v. Trump, No. 25-cv-1240 (D. Md. Apr. 15, 2025)

https://courtlistener.com/docket/69900792/quintanilla-portillo-v-trump/.

+ Sanchez Puentes v. Trump, 25-cv-0127 (W.D. Tex.)

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69905770/sanchez-puentes-v-garite/

+ F.J.G.C. v. Noem, 1:25-cv-04107 (N.D. Il.)

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69897115/cg-v-smith/ [das Verfahren firmiert dort als C.G. v. Smith (1:25-cv-04107)].

Schnelle Entscheidung zu erwarten / Zusammensetzung des Appeals Court-Spruchkörper

12. Mit einer Entscheidung des Appeals Court dürfte angesichts der Kürze der Antwort- und Rück-Antwort-Fristen, die das Gericht festsetzte – und angesichts dessen, daß die Trump-Regierung gebeten hatte, bis Dienstag zu entscheiden – schnell zu rechnen sein.

Der zuständige Spruchkörper besteht aus: Richter Hartz (2001 von George W. Bush nominiert), Richter Phillips (2013 von Obama nominiert) und dem 2013 von Trump nominierten Richter Joel M. Carson.

[*] 50 USC 21 Satz 1 lautet in Gänze:

„Whenever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government, and the President makes public proclamation of the event, all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being of the age of fourteen years and upward, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as alien enemies.“

(https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title50-section21&num=0&edition=prelim; Hv. hinzugefügt)