Wie berichtet, hat der District Court für den Soutern District des Bundesstaates New York bereits zweimal vorläufigen Rechtsschutz gegen die Anwendung der Tren de Argua-Proklation von Präsident Trump, die sich ihrerseits auf den Alien Enemies Act (50 USC 21 – 24) beruft, gewährt. Jetzt hat der dort zuständige Richter Hellerstein (1998 vom damaligen Präsidenten Clinton nominiert) seine bisherige, kurzfristige Temporary Restraining Order (TRO – ‚Eil-Eil-Rechtschutz‘) in eine längerfristige Preliminary Injunction (PI – ‚Eil-Rechtschutz‘) umgewandelt und die jetzige Entscheidung ausführlicher begründet als die bisherigen.

Im Vergleich mit der Entscheidung des District Court für Südtexas vom 1. Mai durch einen von Trump nominierten Richter (siehe taz-Blogs vom selben Tage) fallen mehrere Unterschiede auf:

1. In Süd-New York handelt es sich – anders als in Südtexas – noch nicht um ein Final Judgment. (Beide Entscheidung gelten nur für den jeweiligen Gerichtsbezirk und ergänzen sich daher.)

2. a) Anders als der südtexanische Richter rückt der Süd-New-Yorker Richter nun wieder – wie die der texanischen Entscheidung vorausgegangenen Entscheidungen – die Verfahrensrecht der Betroffenen in den Vorgrund. Dieser Passage ist die Überschrift des hiesigen Artikels entnommen („Rule by the ipse dixit of a President is likely more efficient than the deliberative procedures of a court.“); im unmittelbaren Anschluß daran heißt es:

„But it [the deliberative procedures of a court] is what our Constitution, and the rule of law, demand.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.nysd.640153/gov.uscourts.nysd.640153.84.0.pdf, S. 14; lat. ipse = dt. u.a. selber; lat. dixit = 3. Pers. Sing. Perfekt von lat. dīcere [1. Pers. Sing. Präs.: dīco] = dt. sagen, verkünden, befehlen)

b) In dem Zusammenhang betont der New Yorker Richter zwei Dinge, die bisher keine oder geringe Beachtung fanden:

aa)

In 50 USC 21 Satz 1 heißt es, unter bestimmten Voraussetzungen

„all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being of the age of fourteen years and upward, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as alien enemies.“

In Trumps Proklamation heiß es dagegen:

„I direct that all Alien Enemies described in section 1 of this proclamation are subject to immediate apprehension, detention, and removal, and further that they shall not be permitted residence in the United States.“

(90 Fed. Reg. 13033 – 13036 [13034])</blockquotebb)

50 USC 23 bestimmt:

„After any such proclamation has been made, the several courts of the United States, having criminal jurisdiction, and the several justices and judges of the courts of the United States, are authorized and it shall be their duty, upon complaint against any alien enemy resident and at large within such jurisdiction or district, to the danger of the public peace or safety, and contrary to the tenor or intent of such proclamation, or other regulations which the President may have established, to cause such alien to be duly apprehended and conveyed before such court, judge, or justice; and after a full examination and hearing on such complaint, and sufficient cause appearing, to order such alien to be removed out of the territory of the United States, or to give sureties for his good behavior, or to be otherwise restrained, conformably to the proclamation or regulations established as aforesaid, and to imprison, or otherwise secure such alien, until the order which may be so made shall be performed.“

(Hv. hinzugefügt)In der Proklamation wird dagegen weder 50 USC 23 erwähnt, noch kommen dort die Wörter „complaint“, „examination“ und „hearing“ vor.

cc)

Der Richter schlußfolgert:

„the Presidential Proclamation, in mandating removal without due process, contradicts the AEA.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.nysd.640153/gov.uscourts.nysd.640153.84.0.pdf, S. 2)3. Auch der New Yorker Richter weicht allerdings der Frage, ob der Alien Enemies Act auf Tren de Aragua überhaupt anwendbar ist, nicht aus – und gelangt (jedenfalls vorläufig) zu dem gleichen Ergebnis, wie der texanische Richter bereits endgültig:

„Respondents have not demonstrated the existence of a ‚war,‘ ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion,‘ the AEA was not validly invoked by the Presidential Proclamation.“

(ebd.)a) Auch er leitet seine diesbzgl. Begründung mit – in deutschen Gerichtsentscheidungen leider häufig zu vermissenden – methodologischen Ausführungen ein:

„A statute should be interpreted as to its plain meaning at the time of its adoption, in the context of the events of that time. See Wisconsin Central Ltd. v. United States, 585 U.S. 274, 277 (2018) (‚As usual, our job is to interpret the words consistent with their ›ordinary meaning … at the time Congress enacted the statute.‹‘) (quoting Perrin v. United States, 444 U.S. 37, 42 (1979))); Consumer Prod. Safety Comm’n v. GTE Sylvania, Inc., 447 U.S. 102, 108 (1980) (‚[T]he starting point for interpreting a statute is the language of the statute itself.‘); see also Utah v. Evans, 536 U.S. 452, 492 (2002) (‚Dictionary definitions contemporaneous with the ratification of the Constitution inform our understanding.‘) (Thomas, J., concurring).“

(ebd., S. 16; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)(Deutsche Gerichte beginnen – statt mit Wortlaut der zu interpretierenden Norm – dagegen häufig mit einem freihändig behaupten „Zweck“ der jeweiligen Norm, der aber überhaupt erst einmal methodengerecht – d.h.: unter Beachtung des Wortlauts als Ausgangspunkt und Grenze der Auslegung [*] – ermittelt werden müßte [**].)

b) Das Ergebnis seiner Analyse (S. 16 unten bis 18 unten):

„I hold that the predicates for the Presidential Proclamation, that TdA has engaged in either a ‚war,‘ ‚invasion‘ or a ‚predatory incursion‘ of the United States, do not exist. […]. There is nothing in the AEA that justifies a finding that refugees migrating from Venezuela, or TdA gangsters who infiltrate the migrants, are engaged in an ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion.‘ They do not seek to occupy territory, to oust American jurisdiction from any territory, or to ravage territory. TdA may well be engaged in narcotics trafficking, but that is a criminal matter, not an invasion or predatory incursion.“

(ebd., S. 18)Der Richter expliziert leider nicht,

ob er die Wirklichkeit oder die Behauptungen der Trump-Proklamation (in Bezug auf die Wirklichkeit) an dem Gesetz mißt

und

ob er sich als befugt ansieht, auch zu überprüfen,

ob die Behauptungen wahrgemäß sind,

oder nur, ob denn zumindest die Regierungs-Behauptungen dem Gesetz entsprechen (oder dahinter zurückbleiben).

(Der texanische Richter stellte vergangene Woche vor allem darauf ab, daß nicht einmal die Behauptungen dem Gesetz entsprechen, was theoretisch die Möglichkeit offen läßt, die Behauptungen nachzubessern.)

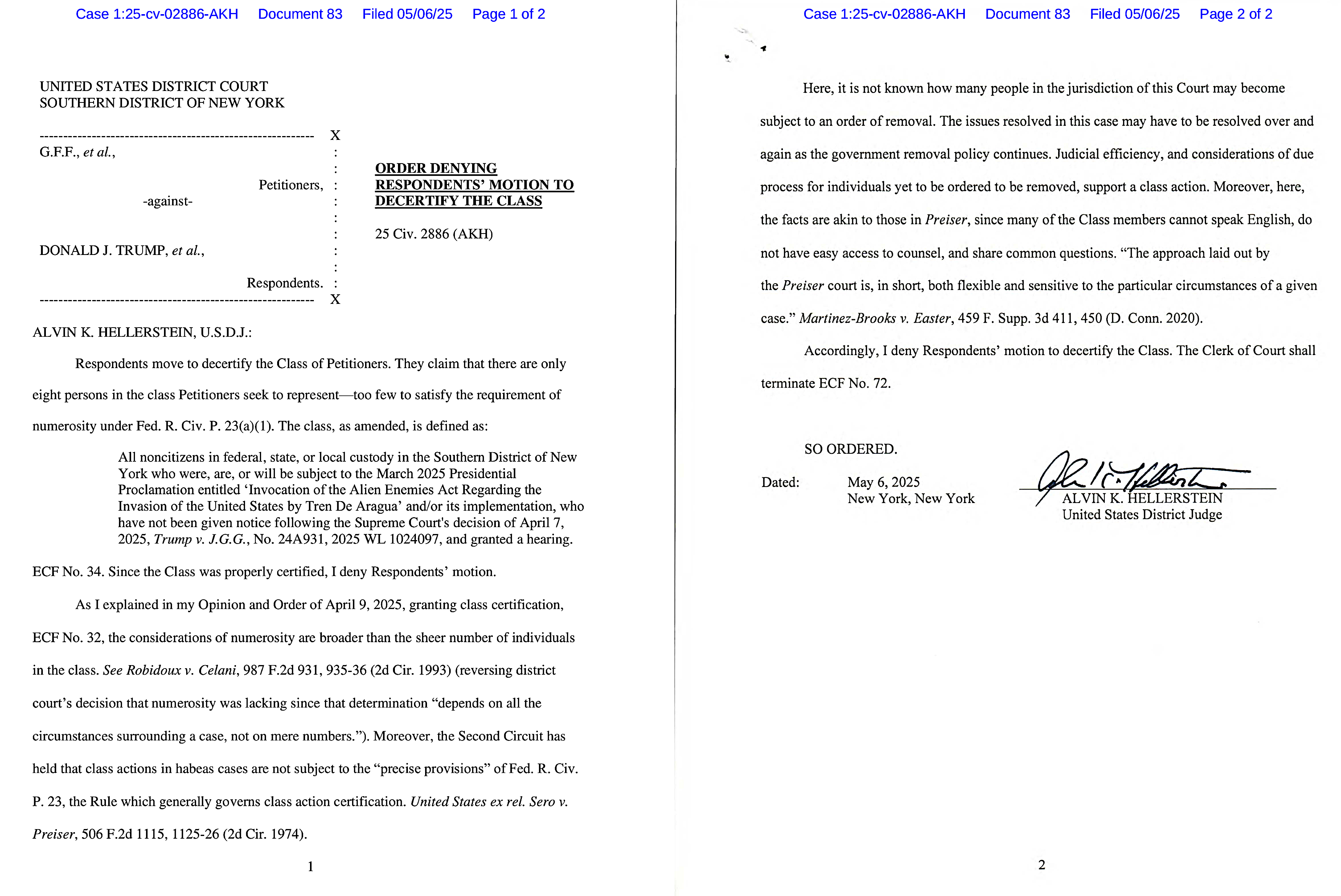

4. Ergänzend entschied der Richter (zu: 72 Motion to Vacate):

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.nysd.640153/gov.uscourts.nysd.640153.83.0.pdf (2 Seiten)

PS.:

1. Die gestern begonnene Serie wird morgen fortgesetzt.

2. Es kommen gleich noch zwei Kurzmeldungen zu den USA (siehe schon mal 1 [zum Fall „Christian“] und 2 [Motion to Intervene and Unseal Court Records im Fall Abrego Garcia]).

[*]

„in interpreting a statute a court should always turn first to one, cardinal canon before all others. We have stated time and again that courts must presume that a legislature says in a statute what it means and means in a statute what it says there. […] When the words of a statute are unambiguous, then, this first canon is also the last: ‚judicial inquiry is complete.‘ Rubin v. United States, 449 U.S. 424, 430 (1981); see also Ron Pair Enterprises, supra [United States v. Ron Pair Enterprises Inc., 489 U.S. 235], at 241.“

(Connecticut National Bank v. Germain, 503 U.S. 249 [253 f.] [1992]; Hv. hinzugefügt)[**]

„Gesichtspunkte von ‚Sinn und Zweck‘ der zu deutenden Norm [sind] nur insoweit heranzuziehen […], als sie mit Hilfe der anderen Elemente belegt werden können. ‚Sinn und Zweck‘ ist, anders gesagt, keine Methode, sondern bereits ein Ergebnis.“

(Friedrich Müller / Ralph Christensen, Juristische Methodik. Band I, 201311, S. 383, RN 364)