Der von US-Präsident Trump – während dessen erster Amtszeit – 2017 nominierte Richter am District Court für Südtexas, Fernando Rodriguez, der den dortigen Antragstellern bereits vorläufigen Rechtsschutz gewährt hatte (siehe taz-Blogs vom 09. und 25.04.2025), bereitet der Trump-Regierung jetzt – mit mehreren Entscheidungen vom heutigen Tage (1, 2 und 3) – eine juristische Niederlage auf nahezu ganzer Linie in Sachen in Aliens Enemies Act / Tren de Aragua-Proklamation:

Hauptpunkte der heutigen Entscheidungen des District Court Südtexas

I. „The question that this lawsuit presents is whether the President can utilize a specific statute, the AEA, to detain and remove Venezuelan aliens who are members of TdA. As to that question, the historical record renders clear that the President’s invocation of the AEA through the Proclamation exceeds the scope of the statute and is contrary to the plain, ordinary meaning of the statute’s terms. As a result, the Court concludes that as a matter of law, the Executive Branch cannot rely on the AEA, based on the Proclamation, to detain the Named Petitioners and the certified class, or to remove them from the country.“ (ORDER AND OPINION regarding 42 MOTION for Preliminary Injunction, S. 2; Hv. hinzugefügt)

„the President’s invocation of the AEA through the Proclamation exceeds the scope of the statute and, as a result, is unlawful. Respondents do not possess the lawful authority under the AEA, and based on the Proclamation, to detain Venezuelan aliens, transfer them within the United States, or remove them from the country.“ (ebd., S. 34; Hv. hinzugefügt)

II. „Petitioners contend that the Respondents’ intended application of the AEA fails to satisfy the requirements of the statute itself and to provide adequate due process to the individuals designated as alien enemies. […]. Respondents emphasize that as to the Named Petitioners, any challenge to the adequacy of the notice is moot, as Named Petitioners have challenged their designation as alien enemies. […]. As to the Named Petitioners, the Court agrees. […]. The same cannot be said for class members, which include individuals who currently or in the future are detained or reside in the Southern District of Texas and who Respondents designate as alien enemies under the Proclamation. The notice procedures may adversely affect them, to the extent that inadequacies in the notice procedures may prevent them from initiating a habeas action before their removal. Ultimately, however, the Court need not reach this issue, given its conclusions as to other issues that the Petitioners present.“ (ebd., S. 21 f.; Hv. hinzugefügt)

III. „The Court has concluded that J.A.V., J.G.G., and W.G.H., in their individual capacity and as representatives of the certified class, have demonstrated entitlement to relief in habeas. Respondents have designated or will designate them as alien enemies under the Proclamation, subjecting them to unlawful detention, transfer, and removal under the AEA. As a result, J.A.V., J.G.G., and W.G.H. are each entitled to the granting of their Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, and a permanent injunction prohibiting Respondents from employing the Proclamation and the AEA against them. The certified class warrants similar protection. The Court will issue a Final Judgment with the appropriate relief.“ (ebd., S. 36; Hv. hinzugefügt)

IV. „ORDERED that the Petitioner’s Motion for Class Certification (Doc. 4) is GRANTED to the extent indicated in this Order and Opinion;

ORDERED that the Court certifies a class of Venezuelan aliens, 14 years old or older, who have not been naturalized, who Respondents have designated or in the future designate as alien enemies under the March 14, 2025, Presidential Proclamation entitled ‘Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of the United States by Tren De Aragua’, 90 Fed. Reg. 13033, and who are detained or reside in the Southern District of Texas; and

ORDERED that Lee Gelernt of the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation is appointed lead counsel for the certified class, and all ACLU attorneys who have appeared in this matter as counsel of record for Named Petitioners are appointed co-counsel for the certified class.“

(ORDER AND OPINION granting 4 MOTION to Certify Class, S. 12; Hyperlink + Hv. hinzugefügt)

Besonderheiten im Vergleich mit den bisherigen Entscheidungen zur Tren de Aragua-Proklamation

Die Entscheidung ist – im Vergleich mit den bisherigen Entscheidungen zur Tren de Aragua-Proklamation – unter drei weiteren Gesichtspunkten bemerkenswert:

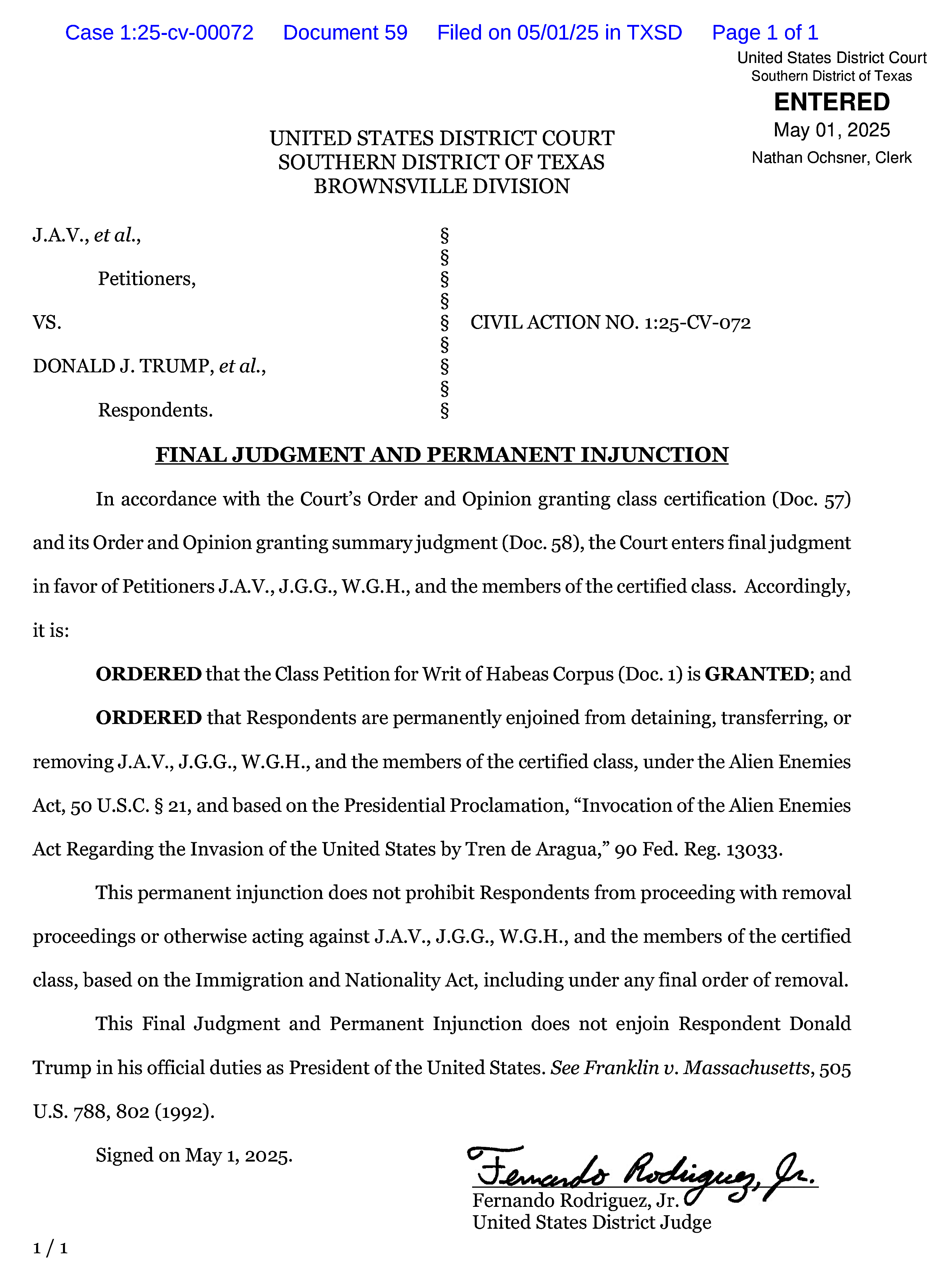

1. Die Entscheidung ist nicht nur vorläufiger Rechtsschutz, sondern bereits ein(e) FINAL JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION (sie kann aber beim übergeordneten 5. Appeals Court angefochten werden, dessen Entscheidung dann wiederum beim Supreme Court angefochten werden kann; Joyce Alene: „On to the 5th Circuit & SCOTUS.“):

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txsd.2000771/gov.uscourts.txsd.2000771.59.0_1.pdf; die am Ende genannte Supreme Court-Entscheidung Franklin v. Massachusetts, 505 U.S. 788, 802 (1992) gibt es dort: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep505/usrep505788/usrep505788.pdf)

„The ruling marks the first time a federal judge has declared President Donald Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act unlawful, with the judge rebuking the president’s claim that Tren de Aragua is invading the United States. […]. While other judges have temporarily blocked the Trump administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act, most have done so on an emergency basis without weighing in on the ‚merits‘ or lawfulness of the proclamation.“

(https://abcnews.go.com/US/judge-blocks-alien-enemies-act-deport-venezuelans-texas/story?id=121364022)

2. Sie rückt nicht die mangelhaften Verfahrensrechte der Betroffenen, sondern die inhaltiche (deutsch-juristisch: „materielle“) Gesetzwidrigkeit der Trump-Proklamation in den Vordergrund.

3. Nicht nur Abschiebungen, sondern auch Inhaftierungen auf Grundlage der Tren de Aragua-Proklamation werden für gesetzwidrig erklärt. –

Varia

Das Ganze steht selbstverständlich nicht Abschiebungen auf Grundlage des ’normalen‘ US-AusländerInnenrechts entgegen, sofern die dort statuierten Abschiebungsvoraussetzungen gegeben sind:

„To the extent that J.A.V., J.G.G., and W.G.H., or any member of the certified class, have been detained or are detained in the future pursuant to the Immigration and Nationality Act, they have not sought and do not obtain any relief. In addition, the conclusions of the Court do not affect Respondents’ ability to continue removal proceedings or enforcement of any final orders of removal issued against J.A.V., J.G.G., and W.G.H, or against any member of the certified class, under the Immigration and Nationality Act.“

(https://t1p.de/qy4q8, S. 36)

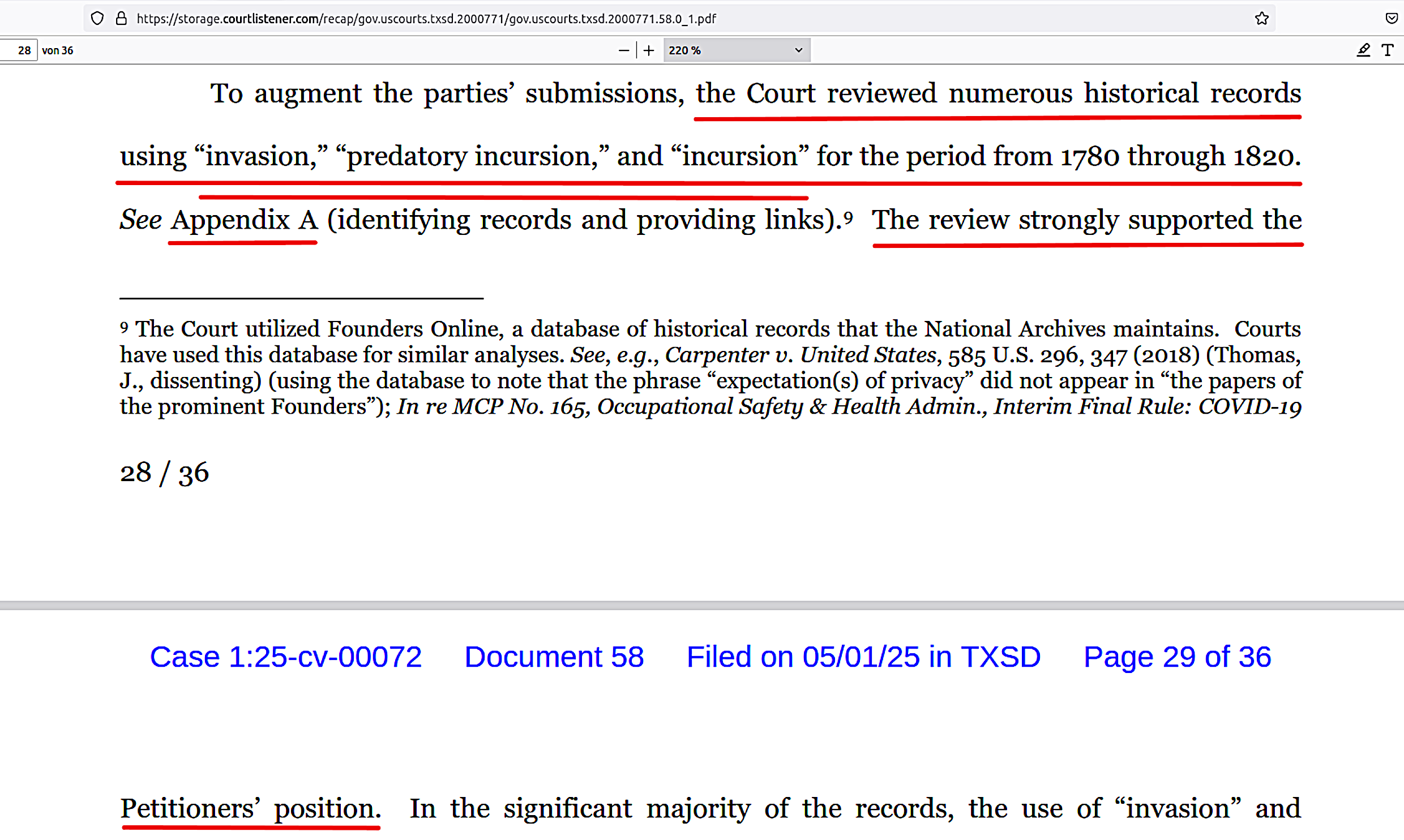

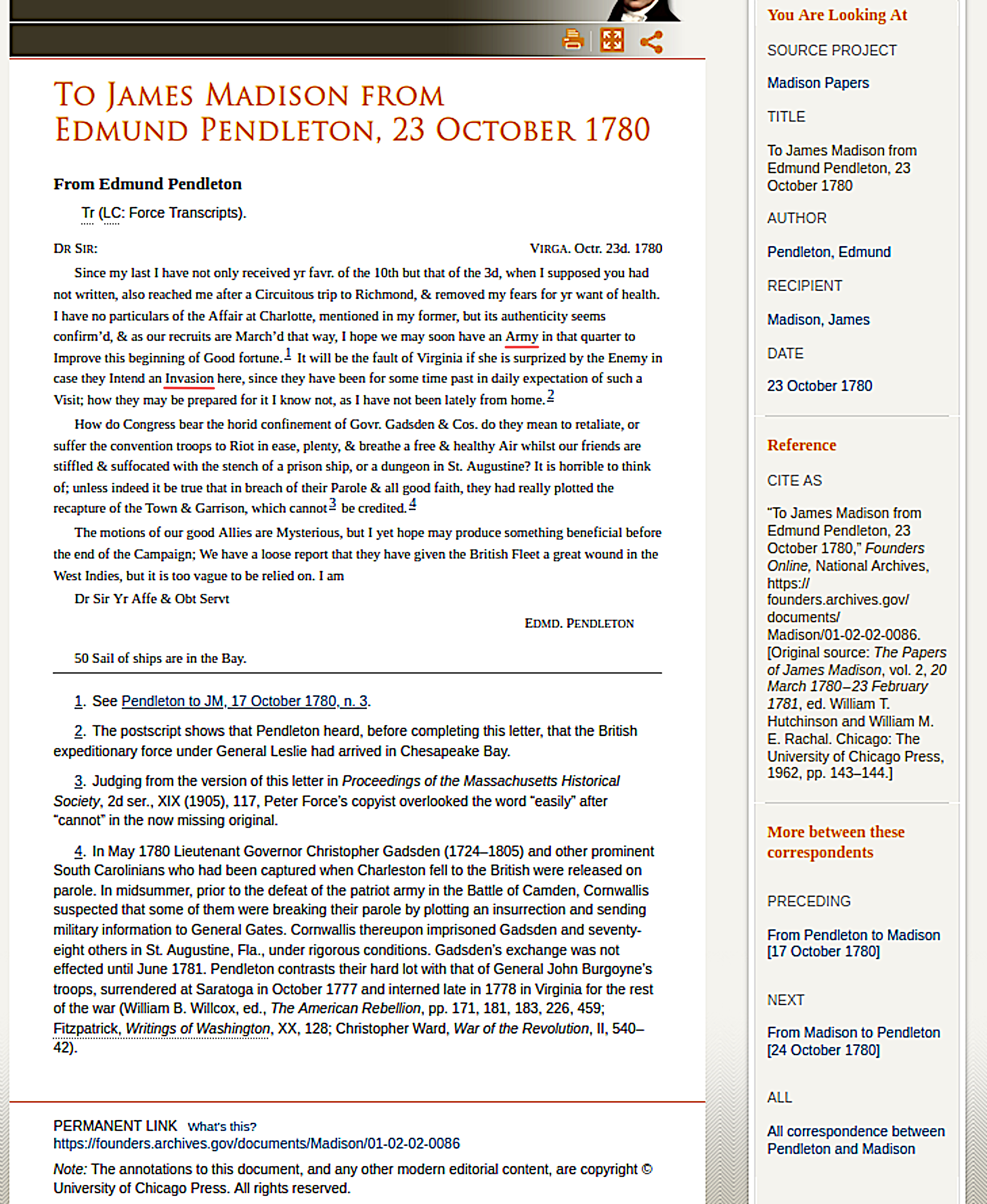

Den philologisch-orginalistischen Anhang mit anklickbaren Hyperlinks (siehe Bild im Artikel-Kopf) zu der ORDER AND OPINION regarding 42 MOTION for Preliminary Injunction gibt es dort:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txsd.2000771/gov.uscourts.txsd.2000771.58.1.pdf.

Zum Beispiel führt Anklicken des ersten Links dort hin:

Siehe auch:

„Unlawful“: Harry Litman and Adam Klasfeld discuss blockbuster immigration ruling against Trump. We break down a Trump-appointed judge’s ruling demolishing the purported legal basis for sending immigrants to El Salvador — and what’s next.

https://www.allrisenews.com/p/unlawful-harry-litman-and-adam-klasfeld

Joyce Vance, Trump Appointed Judge: Trump Can’t Use The Alien Enemies Act

https://joycevance.substack.com/p/trump-appointed-judge-trump-cant

Gliederung einer der Entscheidungen

Gliederung der ORDER AND OPINION regarding 42 MOTION for Preliminary Injunction:

[Einleitung] (S. 1 – 2)

I. Background and Procedural History (S. 2 – 9)

A. Alien Enemies Act (S. 2 – 4)

B. Venezuela and Tren de Aragua (S. 4 – 7)

C. Petitioners (S. 7 – 9)

II. Analysis (S. 10 – 36)

A. Applicable Standard (S. 10 – 11)

B. Political Question (S. 11 – 20)

C. Adequacy of Notice and Notice Procedures (S. 20 – 22)

D. Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act (S. 23 – 34)

- 1. “Invasion” and “Predatory Incursion” (S. 26 – 31)

- 2. “Foreign Nation or Government” (S. 31 – 32)

- 3. Application (S. 32 – 34)

E. Convention against Torture (S. 34 – 36)

III. Conclusion (S. 36)

Der Abschnitt „Analysis“ der ORDER AND OPINION regarding 42 MOTION for Preliminary Injunction

Sehen wir uns nun den Abschnitt Analysis der ORDER AND OPINION regarding 42 MOTION for Preliminary Injunction an.

Am Anfang des Abschnittes werden zunächst die Hauptthesen beider Seiten dargestellt:

„Petitioners seek habeas relief by challenging the President’s invocation of the AEA on three grounds. First, they contend that the Proclamation fails to provide Petitioners with reasonable notice and a meaningful opportunity to challenge their designation as alien enemies. Second, they argue that the Proclamation ‚does not fall within the statutory bounds of the AEA,‘ both because no ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion‘ has occurred or been threatened, and no ‚foreign nation or government‘ has engaged in such conduct. (PI Mot., Doc. 42, 22) And third, Petitioners claim that the Proclamation ‚violates the specific protections that Congress established under the INA for noncitizens seeking humanitarian protection.‘ (Id. at 30)

Respondents contest the validity of each ground. In addition, Respondents present the threshold question of whether the Court may consider the issues at all, arguing that ’no jurisdiction [exists] to review the President’s Proclamation.‘ (Resp., Doc. 45, 20)“ (S. 10; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

A. Applicable Standard

Das Gericht expliziert sodann den Maßstab, nach dem es entscheidet:

„Summary judgment is appropriate ‚if the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.‘ FED. R. CIV. P. 56(a).“ (S. 10; Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

Zuvor hatte es bereits erklärt:

„Petitioners then filed a Motion for a Preliminary Injunction (Doc. 42), which the parties have fully briefed. On April 24, the Court held a hearing to consider the request for a preliminary injunction, as well as the then-pending Motion for Class Certification (Doc. 4).

At the April 24 hearing, Respondents represented that during the pendency of this habeas action, they would not seek the removal of the Named Petitioners, unless through removal proceedings under the Immigration and Nationality Act. This stipulation negated the Named Petitioners’ request for a preliminary injunction, which would have provided the same protections as the Respondents’ stipulation.

The Court notified the parties that it considered the legal issues raised by the Motion for Preliminary Injunction fully briefed and ready for adjudication. The Court stated that it would convert the Motion for Preliminary Injunction into a motion for summary judgment. See FED. R. CIV. P. 65(a)(2) (permitting trial courts to consolidate a motion for a preliminary injunction with a trial on the merits); Univ. of Texas v. Camenisch, 451 U.S. 390, 395 (1981) (noting that ‚the parties should normally receive clear and unambiguous notice of the court’s intent to consolidate the trial and the hearing either before the hearing commences or at a time which will still afford the parties a full opportunity to present their respective cases‘) (cleaned up). In response to the Court’s inquiry whether the parties objected to this conversion, each side represented that they did not. As a result, the Court will consider the issues that the Motion for Preliminary Injunction raises under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56.“ (S. 9; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

B. Political Question

Das Gericht stellt zunächst die Auffassung der Regierung dar:

„The Respondents contend first that the ‚President’s authority and discretion under the AEA is not a proper subject for judicial scrutiny.‘ (Resp., Doc. 45, 20) Relatedly, they claim that ‚[w]hether the AEA’s preconditions are satisfied is a political question committed to the President’s discretion[.]‘ (Id. at 21)“ (S. 11; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Der District Court Südtexas stellt dann (genauso kurz) die Gegenauffassung der Antragsteller dar und analysiert schließlich die bisherige Rechtsprechung zur Political Question Doctrine. Dabei kommt der District Court dann auf S. 15 auf die erste Supreme Court-Entscheidung zur Tren de Aragua-Proklamation („J.G.G.“: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a931_2c83.pdf) zu sprechen: „The Supreme Court in J.G.G. confirmed that ‚questions of interpretation‘ fall within the Judiciary’s responsibility.“

Der District Court kommentiert dies folgendermaßen:

„This role is not surprising, given that whether a government actor’s ‚interpretation of [a] statute is correct . . . is a familiar judicial exercise.‘ Zivotofsky, 566 U.S. at 196; see also Japan Whaling Ass’n v. American Cetacean Soc’y, 106 U.S. 2860, 2866 (1986) (‚[I]t goes without saying that interpreting congressional legislation is a recurring and accepted task for the federal courts.‘).“ (S. 15; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

und führt dann weitere Entscheidungen an. Diese Passage endet mit folgenden Zitaten aus den Entscheidung Harmon v. Brucker, 355 U.S. 579, 582 (1958) und Stark v. Wickard, 321 U.S. 288, 310 (1944):

“The District Court had not only jurisdiction to determine its jurisdiction but also power to construe the statutes involved to determine whether the respondent did exceed his powers.”

“The responsibility of determining the limits of statutory grants of authority in such instances is a judicial function entrusted to the courts by Congress by the statutes establishing courts and marking their jurisdiction.”

und folgender Übertragung dieser Überlegungen auf den Alien Enemies Act:

„As applied to the AEA, this principle signifies that only by construing the meaning of ‚invasion,‘ ‚predatory incursion,‘ and ‚foreign nation or government‘ can the Court analyze whether the President has properly invoked the statute through the Proclamation, or whether he has exceeded his statutory authorization.“ (S. 16)

Der nächste Absatz beginnt dann folgendermaßen: „Consistent with this conclusion, the Second Circuit during the 1940’s construed various provisions of the AEA.“, was wiederum mit verschiedenen Fundstellen belegt wird.

Auf S. 17 betont das Gericht dann:

„But construing the language of the AEA does not require courts to adjudicate the wisdom of the President’s foreign policy and national security decisions. Determining what conduct constitutes an ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion‘ for purposes of the AEA is distinct from ascertaining whether such events have in fact occurred or are being threatened.“

Das Gericht sagt aber auch: „The court having determined the meaning of these terms, it is left to the Executive Branch to determine whether a foreign nation or government has threatened or perpetrated activity that includes such an entry.“ (S. 18)

Dies relativiert das Gericht dann aber wiederum durch folgende Bemerkungen auf S. 19 und 20:

„the Court concludes that a Presidential declaration invoking the AEA must include sufficient factual statements or refer to other pronouncements that enable a court to determine whether the alleged conduct satisfies the conditions that support the invocation of the statute. The President cannot summarily declare that a foreign nation or government has threatened or perpetrated an invasion or predatory incursion of the United States, followed by the identification of the alien enemies subject to detention or removal. Cf. United States v. Abbott, 110 F.4th 700, 736 (5th Cir. 2024) (‚To be sure, a state of invasion under Article I, section 10 does not exist just because a State official has uttered certain magic words.‘) (Ho, J., concurring).“

„While a President’s declaration invoking the AEA need not disclose all of the information that the Executive Branch possesses to support its invocation of the statute, it must identify sufficient information to permit judicial review of whether the foreign nation or government’s conduct constitutes an actual, attempted, or threatened invasion or predatory incursion of the United States. [FN 7:] In appropriate circumstances, courts may also employ tools such as the submission of sensitive information for in camera review.“ (Fußnote 7 in den Haupttext eingefügt und Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

Das Ergebnis ist insoweit also:

„the political question doctrine does not preclude the Court from considering some of the arguments that Respondents present, the Court turns to those permissible areas of inquiry.“ (S. 20)

C. Adequacy of Notice and Notice Procedures

In diesem Abschnitt heißt es auf S. 20 und 21:

„Petitioners contend that the Respondents’ intended application of the AEA fails to satisfy the requirements of the statute itself and to provide adequate due process to the individuals designated as alien enemies. (PI Mot., Doc. 42, 20) […]. Respondents emphasize that as to the Named Petitioners, any challenge to the adequacy of the notice is moot, as Named Petitioners have challenged their designation as alien enemies. (Resp., Doc. 45, 18 (‚[T]his very proceeding refutes that claim.‘)) […]. As to the Named Petitioners, the Court agrees. […]. The same cannot be said for class members, which include individuals who currently or in the future are detained or reside in the Southern District of Texas and who Respondents designate as alien enemies under the Proclamation. The notice procedures may adversely affect them, to the extent that inadequacies in the notice procedures may prevent them from initiating a habeas action before their removal. Ultimately, however, the Court need not reach this issue, given its

conclusions as to other issues that the Petitioners present.“ (Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Diesbezüglich hat der District Court Südtexas also weder den Antragstellern noch der Regierung Recht gegeben, sondern die Frage offen gelassen.

D. Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act

Das Gericht legt zunächst seine Methoden (Auslegungsgesichtspunkte) dar, mit der es das Gesetz interpretiert – etwas, das deutsche Gerichte auch öfter tun sollten (erstens überhaupt [wg. Methoden-Transparenz] und zweitens genau mit dem Vorrang der grammatisch-philologischen Interpretation [wg. der Rechtssicherheit <Berechenbarkeit des Zuschlagens der Staatsgewalt> <*> und, weil Gesetzesinterpretation und Gesetzgebung zweierlei sind] – die Präferenz für diese Methode wird in den USA als Textualismus bezeichnet):

„Courts normally interpret statutory terms ‚consistent with their ordinary meaning at the time Congress enacted the statute.‘ Wisconsin Cent. Ltd v. United States, 585 U.S. 274, 277 (2018) (cleaned up); see also Texas v. Trump, 127 F.4th 606, 611 (5th Cir. 2025) (‚Absent congressional direction to the contrary, words in statutes are to be construed according to their ordinary, contemporary, common meanings.‘) (cleaned up) (citing Kennedy v. Tex. Utils., 179 F.3d 258, 261 (5th Cir. 1999); Griffin v. Oceanic Contractors, Inc., 458 U.S. 564, 571 (1982) (‚[N]o more persuasive evidence of the purpose of a statute [exists] than the words by which the legislature undertook to give expression to its wishes.‘) (citing United States v. American Trucking Assns., Inc., 310 U.S. 534, 543 (1940)).“ (S. 23; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Der süd-texanische Richter macht noch einen Zusatz, der Originalismus genannt wird:

„When ascertaining the plain, ordinary meaning of statutory language that harkens back to the nation’s founding era, courts rely on contemporaneous dictionary definitions and historical records that reveal the common usage of the terms at issue. See, e.g., D.C. v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 581–83 (2008) (examining founding era writings and commentaries to determine the commonly understood meaning of ‚keep and bear arms‘); Utah v. Evans, 536 U.S. 452, 492 (2002) (Thomas, J., concurring) (‚Dictionary definitions contemporaneous with the ratification of the Constitution inform our understanding.‘); see also Cascabel Cattle Co., L.L.C. v. United States, 955 F.3d 445, 451 (5th Cir. 2020) (considering dictionary definitions from the 1930’s to construe the meaning of terms within the Federal Tort Claims Act, enacted in 1946); […].“ (S. 23; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

(Zu beiden methodologischen Ansätzen – Textualismus und Originalismus – hatte ich im Februar in einem Interview, das Achim Schill mit mir für das Schweizer untergrundblättle führte [https://www.untergrund-blättle.ch/politik/deutschland/die-usa-unter-trump-und-musk-teil-4-rechtspopulismus-in-den-usa-und-der-brd-008929.html], Stellung genommen.)

Sodann äußert sich der Richter zu dem Problem, daß Wörter nicht immer eine eindeutige Bedeutung haben:

„While most English words have multiple dictionary meanings, courts ‚use the ordinary meaning of terms unless context requires a different result.‘ Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 152 (2007). At times, terms can hold more than one ordinary meaning. See, e.g., United States v. Santos, 553 U.S. 507, 511 (2008) (finding that the word ‚proceeds‘ in a money laundering statute had the commonly accepted meanings of ‚receipts‘ or ‚profits‘). Reviewing courts, however, apply ‚the contextually appropriate ordinary meaning, unless there is reason to think otherwise.‘ ANTONIN SCALIA & BRYAN A. GARNER, READING LAW: THE INTERPRETATION OF LEGAL TEXTS 70 (2012).“ (S. 24; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

„The canon of noscitur a sociis at times proves relevant. A statutory word or phrase derives ‚more precise content by the neighboring words with which it is associated.‘ United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285, 294 (2008); see also United States v. Santiago, 96 F.4th 834, 847 (5th Cir. 2024) (‚[W]e must apply noscitur a sociis to understand ›use‹ as akin to, but with a meaning different from, ›open, lease, rent, … or maintain.‹‘). Adhering to this canon ‚avoid[s] ascribing to one word a meaning so broad that it is inconsistent with its accompanying words, thus giving unintended breadth to the Acts of Congress.‘ Yates v. United States, 574 U.S. 528, 537 (2015); Fischer v. United States, 603 U.S. 480, 487 (2024) (explaining that noscitur a sociis ‚avoid[s] ascribing to one word a meaning so broad that it is inconsistent with … the company it keeps‘) (quoting Gustafson v. Alloyd Co., 513 U.S. 561, 575 (1995)).“ (S. 25; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

(Dies entspricht in etwa dem, was im deutschen Sprachgebrauch systematische Auslegung oder systematischer Auslegungsgesichtspunkt genannt wird, die bzw. der freilich hierzulande „durch den Siegeszug der Wertungsjurisprudenz“ genauso „an Bedeutung eingebüßt“ hat [Röhl, Allgemeine Rechtslehre, 1995, 644], wie die oben erwähnte grammatisch-philogische Auslegung.)

Außerdem kommt der District Court in etwa auf das zu sprechen, was hierzulande historische und/oder genealogische Auslegung genannt wird:

„The historical context for the enactment of a statute can prove relevant, but does not dictate the statutory words’ meaning. See, e.g., Airlines for Am. v. Dep’t of Transportation, 110 F.4th 672, 676 (5th Cir. 2024) (confirming that ‚legislative history is not the law,‘ and it cannot ‚muddy clear statutory language‘); Gundy v. United States, 588 U.S. 128, 141 (2019) (explaining that when attempting to ‚define the scope of delegated authority,‘ courts may look at ‚the purpose of the Act, its factual background and the statutory context‘). Again, courts seek to apply the plain, ordinary meaning of the words that Congress chose, rather than the subjective intent that Congress or, more accurately, certain members of Congress may have held regarding the statute. See, e.g., Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 597 U.S. 629, 642 (2022) (‚[T]he text of a law controls over purported legislative intentions unmoored from any statutory text.‘).“(S. 25; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

(Ich stimme wiederum zu: Während es zwar nicht Aufgabe der Gerichte ist, ihren Willen oder ihr ‚Rechtsgefühl‘ an Stelle des Willens der Gesetzgebungsorgane zu setzen, soweit es letzteren gelungen ist, ihren Willen [klar] zu Papier zu bringen, ist es zugleich Aufgabe der Gesetzgebungsorgane – wiederum Interesse der Rechtssicherheit – sich klar auszudrücken – und wenn ihnen das nicht gelungen ist und sie sich von den Gerichten mißverstanden fühlen [oder zu neuer Einsicht gekommen sind], dann können sie ihre Gesetze ja ändern. Auch wenn Kontexte relevant sind, so sind doch verscheidene Kontexte „voneinander abzuschichten und entsprechend ihrer Nähe zum fraglichen Normtext zu gewichten“ [Müller/Christensen, Juristische Methodik. Band I, 201311, 370 <361>].)

Die Einleitung des Abschnittes „D. Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act“ endet mit folgendem Satz:

„With these principles in mind, the Court turns to the meaning of the disputed words and phrases in the AEA.“

1. ‚Invasion‘ and ‚Predatory Incursion‘

Sehen wir uns nun in Gänze den Unterabschnitt „1. ‚Invasion‘ and ‚Predatory Incursion'“ (S. 26 unten – 31 unten) an:

(Ich würde meinerseits etwas weniger schnell auf den gewöhnlichen (ordinary) Sprachgebrauch zu sprechen kommen und vielmehr erst einmal die äußerste Grenze der Wortbedeutungen abstecken – und diesbzgl. zunächst einmal der Regierung Recht geben (vorausgesetzt, deren beiden Wörterbuch-Zitate sind korrekt [was ich nicht überprüft habe]: „hostile entrance“ und „hostile encroachment“). Sodann würde ich allerdings – sehr ähnlich wie der District Court Südtexas – diese äußerste Wortlautgrenze einengen und die im konkreten Kontext des Alien Enemies Act gegebene Bedeutung ermitteln – also dem Sprachgebrauch der Gesetz- und Verfassungsgeber [Frauenwahlrecht gab es noch nicht] am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts mehr Gewicht geben als zwei Wörterbüchern. In diesem Zusammenhang wäre ich dann auch dem noscitur a sociis-Argument („A principle or guide to interpretation that suggests the understanding of an unclear or ambiguous term (like one in a law or agreement) can be resolved by looking at the words surrounding it in the text“ [Justia]; nōscitur = 3. Pers. Singular Präsens Passiv zu nōscere [1. Pers. Singlar Präsens Aktiv: nosco] = u.a. kennenlernen, erkennen) der Antragsteller gegenüber aufgeschlossener als der District Court:

-

Ich würde zwar dem District Court in folgendem zustimmen: „The structure of the AEA does not require that the latter two (‚invasion‘ and ‚predatory incursion‘) must be precursors to the first (‚declared war‘).“

-

Aber weder daraus, noch aus dem Wort „or“ in 50 U.S.C. § 21 folgt, daß in dieser konkreten Norm ‚invasion‘ und ‚predatory incursion‘ nicht zumindest etwas ähnliches wie Krieg ist (sei er erklärt oder nicht).

-

Durchaus fraglich ist aber, ob dieses Ähnlichkeits-Kriterium mehr verlangt als der District Court verlangt – nämlich: „organized, armed force entering the United States to engage in conduct destructive of property and human life in a specific geographical area„. Ich würde vermutlich noch die Wörter „Kriegswaffen“ und „militärisch“ hinzufügen, ob die Abgrenzung gegebenüber x-beliebigem bewaffneten Vorgehen schärfer zu fassen).

2. “Foreign Nation or Government”

Der nächste Unterabschnitt ist (einschließlich Überschrift) nur 16 Zeilen lang und endet folgendermaßen:

„Neither party claims that ‚foreign nation or government‘ excludes recognized countries such as the United States and Venezuela. Thus, and for the reasons explained in the next section, the Court finds that resolving the precise meaning of ‚foreign nation or government‘ is unnecessary to resolve the issues in this lawsuit.“ (S. 32)

Die Frage, ob Tren de Aragua eine “foreign nation or government“ bleibt also offen:

„the Court need not reach whether TdA itself represents a ‚foreign nation or government.'“ (S. 34, FN 10)

3. Application

Der nächste Unterabschnitt beginnt dann wie folgt:

„Having determined the meaning of the relevant statutory terms, the Court considers whether as a matter of law, the Proclamation exceeded the statutory boundaries that the AEA establishes. The Court concludes that it did.“ (S. 32)

Das Gericht spricht dann zwei Punkte an, die die beiden vorhergehenden Unterabschnitte wieder aufgreift.

„Foreign Nation or Government“

Als erstes kommt es auf den vorhergehenden Unterabschnitt „Foreign Nation or Government“ zurück:

„the Court finds that the Proclamation places the government of Venezuela as the controlling entity over TdA’s activities in the United States. According to the Proclamation, TdA ‚undertak[es] hostile actions and conduct[s] irregular warfare against the territory of the United States both directly and at the direction … of the Maduro regime in Venezuela.‘ Proclamation, 90 Fed. Reg. 13033 (emphasis added). According to the Proclamation, Maduro, ‚who claims to act as Venezuela’s President … leads the regime-sponsored enterprise Cártel de los Soles, which coordinates with and relies on TdA … to carry out its objective of using illegal narcotics as a weapon[.]‘ Id. (emphasis added). Although the Proclamation focuses on TdA’s activities in the United States, it places control of those activities in Maduro, acting in his claimed role of President of Venezuela. In other words, the Proclamation declares that the country of Venezuela, through Maduro, directs and controls TdA’s activities in the United States. Respondents accurately characterize the Proclamation’s message: ‚TdA has become indistinguishable from the Venezuelan state.‘ (Resp., Doc. 45, 27) As a result, the Court concludes that the Proclamation places responsibility for TdA’s actions in the United States on the Venezuelan government, which satisfies this aspect of the AEA.“ (S. 32; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Das Gericht geht weder auf die Frage ein, ob die zitierten Behauptungen aus der Proklamation faktisch zutreffend sind, noch auf die Inkohärenz, daß

-

nach dem gerichtlichen Verständnis der Proklamation die venezolanische Regierung das letztliche Subjekt der vermeintlichen „invasion“ und „predatory incursion“ sein soll,

-

nach der Proklamation aber nicht „all Venezuelan citizens 14 years of age or older“, sondern ausschließlich „all Venezuelan citizens 14 years of age or older who are members of TdA, are within the United States, and are not actually naturalized or lawful permanent residents of the United States are liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as Alien Enemies“ (Hv. hinzugefügt).

Im Gesetz heißt es aber:

„all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being of the age of fourteen years and upward, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as alien enemies“

(50 USC 21; Hv. hinzugefügt)

Das wären dann aber alle venezolanischen StaatsbürgerInnnen „being of the age [… usw.]“.

Zwar heißt es in dem Gesetz auch:

„The President is authorized in any such event, by his proclamation thereof, or other public act, to direct the conduct to be observed on the part of the United States, toward the aliens who become so liable; the manner and degree of the restraint to which they shall be subject and in what cases, and upon what security their residence shall be permitted, and to provide for the removal of those who, not being permitted to reside within the United States, refuse or neglect to depart therefrom; and to establish any other regulations which are found necessary in the premises and for the public safety.“

(50 USC 21)

Es findet sich in der Proklamation aber kein ausdrückliche Bestimmung, daß alle venezolanischen StaatsbürgerInnnen „being of the age [… usw.]“ alien enemies seien; denen, die keine Tren de Aragua-Mitglieder sind, aber erlaubt bleibe in den USA zu sein (sofern es ihnen nicht aufgrund anderer Normen als dem AEA verboten ist). (Das läßt sich allenfalls aus dem Satz in der Proklamation zu den TdA-Mitgliedern schlußfolgern.)

50 USC 22 unterscheidet ausdrücklich zwischen solchen alien enemies, die „chargeable with actual hostility“ sind, und solchen, die es nicht sind. Es sind also nach dem Wortlaut des Gesetzes keineswegs nur diejenigen, die „chargeable with actual hostility“ sind, die alien enemies.

„invasion“ und „predatory incursion“

Kommen wir nun zu dem zweiten Punkt:

„As for the activities of the Venezuelan-directed TdA in the United States, and as described in the Proclamation, the Court concludes that they do not fall within the plain, ordinary meaning of ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion‘ for purposes of the AEA. As an initial matter, no question exists that the Proclamation references the entry of TdA members into the United States. Proclamation, 90 Fed. Reg. 13033 (declaring that ‚many‘ TdA members have ‚unlawfully infiltrated the United States‘). And these members’ objectives include ‚harming United States’ citizens [and] undermining public safety[.]‘ Id. In addition, the Proclamation also references the decision of a federal agency during the administration of President Joseph Biden to designate TdA as a ’significant transnational criminal organization,‘ which, in relevant part, denotes ‚a group of persons that … engages in or facilitates an ongoing pattern of serious criminal activity … that threatens the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.‘ 31 C.F.R. § 590.312. That designation received substantial public approval, with supporters often referencing the criminal activity that TdA members allegedly engaged in within the United States.

Those factual statements depict conduct by TdA that unambiguously is harmful to society in this country. And as previously explained, the political question doctrine prohibits the Court from weighing the truth of those factual statements, including whether Maduro directs TdA’s actions or the extent of the referenced criminal activity.“ (S. 33)

Theoretisch könnte Trump nun also seine faktischen Behauptungen in der Proklamation so nachbessern, daß sie zur gerichtlichen Definition von „invasion“ und „predatory incursion“ passen. Aber dann käme wir vermutlich (das Gericht äußert sich dazu am Ende nicht klar) zurück zu dem, was oben bereits von S. 19 und 20 der Entscheidung zitiert war:

„the Court concludes that a Presidential declaration invoking the AEA must include sufficient factual statements or refer to other pronouncements that enable a court to determine whether the alleged conduct satisfies the conditions that support the invocation of the statute. The President cannot summarily declare that a foreign nation or government has threatened or perpetrated an invasion or predatory incursion of the United States, followed by the identification of the alien enemies subject to detention or removal. Cf. United States v. Abbott, 110 F.4th 700, 736 (5th Cir. 2024) (‚To be sure, a state of invasion under Article I, section 10 does not exist just because a State official has uttered certain magic words.‘) (Ho, J., concurring).“

„While a President’s declaration invoking the AEA need not disclose all of the information that the Executive Branch possesses to support its invocation of the statute, it must identify sufficient information to permit judicial review of whether the foreign nation or government’s conduct constitutes an actual, attempted, or threatened invasion or predatory incursion of the United States. [FN 7:] In appropriate circumstances, courts may also employ tools such as the submission of sensitive information for in camera review.“ (Fußnote 7 in den Haupttext eingefügt und Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

Der Unterabschnitt „3. Application“ endet – mehr oder minder – folgendermaßen:

„the Court determines whether the factual statements in the Proclamation, taken as true, describe an ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion‘ for purposes of the AEA. Based on the plain, ordinary meaning of those terms in the late 1790’s, the Court concludes that the factual statements do not. The Proclamation makes no reference to and in no manner suggests that a threat exists of an organized, armed group of individuals entering the United States at the direction of Venezuela to conquer the country or assume control over a portion of the nation. Thus, the Proclamation’s language cannot be read as describing conduct that falls within the meaning of ‚invasion‘ for purposes of the AEA. As for ‚predatory incursion,‘ the Proclamation does not describe an armed group of individuals entering the United States as an organized unit to attack a city, coastal town, or other defined geographical area, with the purpose of plundering or destroying property and lives. While the Proclamation references that TdA members have harmed lives in the United States and engage in crime, the Proclamation does not suggest that they have done so through an organized armed attack, or that Venezuela has threatened or attempted such an attack through TdA members. As a result, the Proclamation also falls short of describing a ‚predatory incursion‘ as that concept was understood at the time of the AEA’s enactment.

[FN 11:] The Proclamation also declares that TdA is ‚conducting irregular warfare.‘ Proclamation, 90 Fed. Reg. 13033. Respondents do not contend that a ‚declared war‘ exists between Venezuela and the United States. Thus, to the extent that Respondents argue that “conducting irregular warfare” constitutes an ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion,‘ the Court finds that the language merely refers to the conduct by TdA as described throughout the Proclamation. And that conduct, as the Court has explained, does not depict an ‚invasion‘ or ‚predatory incursion‘ for purposes of the AEA.“ (S. 33 f.; FN 11 in den Haupttext eingefügt; Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

Es kommt dann – in diesem Unterabschnitt – nur noch folgende, eingangs bereits zitierte Passage:

„For these reasons, the Court concludes that the President’s invocation of the AEA through the Proclamation exceeds the scope of the statute and, as a result, is unlawful. Respondents do not possess the lawful authority under the AEA, and based on the Proclamation, to detain Venezuelan aliens, transfer them within the United States, or remove them from the country.“ (S. 34)

E. Convention against Torture

Das Gericht stellt zunächst die Auffassungen beider Seiten dar:

„Petitioners’ final legal theory is that the Proclamation ‚violates the specific protections that Congress established under the INA for noncitizens seeking humanitarian protection.‘ (PI Mot., Doc. 42, 30–31) They explain that the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act codified the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the ‚Convention‘), and that the Convention and United States statutes work together to ‚ensure that noncitizens have meaningful opportunities to seek protection from torture” and to ‚prohibit[ ] returning a noncitizen to any country where they would more likely than not face torture.‘ (Resp. [„Resp.“ scheint ein Tippfehler und vielmehr erneut „PI Mot.“ gemeint zu sein], Doc. 42, 30–31) They submit evidence describing alarming abuses within the El Salvadorean prison, CECOT, to which Petitioners claim the United States has sent and will continue to send individuals designated as alien enemies under the Proclamation. (See Declaration of Juanita Goebertus, Doc. 42–6)

Respondents argue that 8 U.S.C. § 1252(a)(4) “divests this Court of jurisdiction to review any cause or claim under the [Convention].” (Resp., Doc. 45, 25 (quoting Benitez-Garay v. DHS, No. SA-18-CA-422-XR, 2019 WL 542035, at *7 (W.D. Tex. 2019)))“ (S. 34 f.)

8 U.S.C. § 1252(a) lautet:

„(a) Applicable provisions

(1) General orders of removal

Judicial review of a final order of removal (other than an order of removal without a hearing pursuant to section 1225(b)(1) of this title) is governed only by chapter 158 of title 28, except as provided in subsection (b) and except that the court may not order the taking of additional evidence under section 2347(c) of such title.

(2) Matters not subject to judicial review

(A) Review relating to section 1225(b)(1)

Notwithstanding any other provision of law (statutory or nonstatutory), including section 2241 of title 28, or any other habeas corpus provision, and sections 1361 and 1651 of such title, no court shall have jurisdiction to review –

(i) except as provided in subsection (e), any individual determination or to entertain any other cause or claim arising from or relating to the implementation or operation of an order of removal pursuant to section 1225(b)(1) of this title,

(ii) except as provided in subsection (e), a decision by the Attorney General to invoke the provisions of such section,

(iii) the application of such section to individual aliens, including the determination made under section 1225(b)(1)(B) of this title, or

(iv) except as provided in subsection (e), procedures and policies adopted by the Attorney General to implement the provisions of section 1225(b)(1) of this title.

(B) Denials of discretionary relief

Notwithstanding any other provision of law (statutory or nonstatutory), including section 2241 of title 28, or any other habeas corpus provision, and sections 1361 and 1651 of such title, and except as provided in subparagraph (D), and regardless of whether the judgment, decision, or action is made in removal proceedings, no court shall have jurisdiction to review –

(i) any judgment regarding the granting of relief under section 1182(h), 1182(i), 1229b, 1229c, or 1255 of this title, or

(ii) any other decision or action of the Attorney General or the Secretary of Homeland Security the authority for which is specified under this subchapter to be in the discretion of the Attorney General or the Secretary of Homeland Security, other than the granting of relief under section 1158(a) of this title.

(C) Orders against criminal aliens

Notwithstanding any other provision of law (statutory or nonstatutory), including section 2241 of title 28, or any other habeas corpus provision, and sections 1361 and 1651 of such title, and except as provided in subparagraph (D), no court shall have jurisdiction to review any final order of removal against an alien who is removable by reason of having committed a criminal offense covered in section 1182(a)(2) or 1227(a)(2)(A)(iii), (B), (C), or (D) of this title, or any offense covered by section 1227(a)(2)(A)(ii) of this title for which both predicate offenses are, without regard to their date of commission, otherwise covered by section 1227(a)(2)(A)(i) of this title.

(D) Judicial review of certain legal claims

Nothing in subparagraph (B) or (C), or in any other provision of this chapter (other than this section) which limits or eliminates judicial review, shall be construed as precluding review of constitutional claims or questions of law raised upon a petition for review filed with an appropriate court of appeals in accordance with this section.

(3) Treatment of certain decisions

No alien shall have a right to appeal from a decision of an immigration judge which is based solely on a certification described in section 1229a(c)(1)(B) of this title.

(4) Claims under the United Nations Convention

Notwithstanding any other provision of law (statutory or nonstatutory), including section 2241 of title 28, or any other habeas corpus provision, and sections 1361 and 1651 of such title, a petition for review filed with an appropriate court of appeals in accordance with this section shall be the sole and exclusive means for judicial review of any cause or claim under the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, except as provided in subsection (e) <**>.

(5) […].“

(https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title8-section1252&num=0&edition=prelim; Hv. hinzugefügt)

District Court Südtexas schreibt dazu:

„Based on this provision, the Second Circuit concluded that ‚the language of Section 1252(a)(4) plainly bars any habeas review of CAT claims[.]‘ Kapoor, 132 F.4th at 609. […]. The Court finds the reasoning of these decisions persuasive. Section 1252(a)(4) leaves no room for discretion, and divests this Court of considering in this habeas action whether removal under the AEA would violate the Convention. At the hearing on the Motion for Preliminary Injunction, Petitioners’ counsel attempted to distinguish Kapoor on the grounds that it concerns extradition. But that distinction does not narrow the reach of Section 1252(a)(4). As a result, the Court concludes that it does not possess jurisdiction to consider Petitioners’ challenges to the Proclamation based on the Convention.“ (S. 35, 36)

Ich habe mir das noch nicht genau angesehen; aber vorderhand scheint mir das plausibel sein. Jedenfalls scheint es – wenn ich recht sehe – nicht zu bedeuten, daß es in dem Zusammenhang gar keinen Rechtsschutz gibt, sondern nur, daß erstinstanzlich sogleich die Appeals Courts zuständig sind.

Damit sind wie am Ende von Abschnitte „II. Analysis“ angekommen; es folgt danach nur doch Abschnitt „III. Conclusion“. Dessen beiden Absätze waren bereits am Anfang dieses Artikels zitiert worden (siehe dort die beiden Zitate von S. 36 der Entscheidung).

Diese Darstellung der District Court-Entscheidung wird im Laufes des Freitagabend um Hyperlinks zu den in den Zitaten genannte Entscheidungen ergänzt.

<*> Vgl.: „Normklarheit, Tatbestandsbestimmtheit, Methodenklarheit und Rechtssicherheit [sind] für den Umgang mit verfassungsrechtlichen Normen besonders wichtig. Auf die begrenzende Rolle des Wortlauts verfassungsrechtlicher Vorschriften wurde hier schon bei der Analyse verfassungsgerichtlicher Methodik hingewiesen. […]. Seine [des Wortlauts] Grenzfunktion [für die Auslegung] ergibt sich aus seinen normativ geforderten Wirkungen für Rechtssicherheit, Normklarheit, Publizität und für die Unverbrüchlichkeit der Verfassungsordnung“ (Müller/Christensen, Juristische Methodik. Band I, 201311, 143 [Randnummer 113], 307 [Randnummer 311])

<**> 8 U.S.C. § 1252(a) lautet:

„(e) Judicial review of orders under section 1225(b)(1)

(1) Limitations on relief

Without regard to the nature of the action or claim and without regard to the identity of the party or parties bringing the action, no court may –

(A) enter declaratory, injunctive, or other equitable relief in any action pertaining to an order to exclude an alien in accordance with section 1225(b)(1) of this title except as specifically authorized in a subsequent paragraph of this subsection, or

(B) certify a class under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in any action for which judicial review is authorized under a subsequent paragraph of this subsection.

(2) Habeas corpus proceedings

Judicial review of any determination made under section 1225(b)(1) of this title is available in habeas corpus proceedings, but shall be limited to determinations of –

(A) whether the petitioner is an alien,

(B) whether the petitioner was ordered removed under such section, and

(C) whether the petitioner can prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the petitioner is an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence, has been admitted as a refugee under section 1157 of this title, or has been granted asylum under section 1158 of this title, such status not having been terminated, and is entitled to such further inquiry as prescribed by the Attorney General pursuant to section 1225(b)(1)(C) of this title.

(3) Challenges on validity of the system

(A) In general

Judicial review of determinations under section 1225(b) of this title and its implementation is available in an action instituted in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, but shall be limited to determinations of –

(i) whether such section, or any regulation issued to implement such section, is constitutional; or

(ii) whether such a regulation, or a written policy directive, written policy guideline, or written procedure issued by or under the authority of the Attorney General to implement such section, is not consistent with applicable provisions of this subchapter or is otherwise in violation of law.

(B) Deadlines for bringing actions

Any action instituted under this paragraph must be filed no later than 60 days after the date the challenged section, regulation, directive, guideline, or procedure described in clause (i) or (ii) of subparagraph (A) is first implemented.

(C) Notice of appeal

A notice of appeal of an order issued by the District Court under this paragraph may be filed not later than 30 days after the date of issuance of such order.

(D) Expeditious consideration of cases

It shall be the duty of the District Court, the Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court of the United States to advance on the docket and to expedite to the greatest possible extent the disposition of any case considered under this paragraph.

(4) Decision

In any case where the court determines that the petitioner-

(A) is an alien who was not ordered removed under section 1225(b)(1) of this title, or

(B) has demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that the alien is an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence, has been admitted as a refugee under section 1157 of this title, or has been granted asylum under section 1158 of this title, the court may order no remedy or relief other than to require that the petitioner be provided a hearing in accordance with section 1229a of this title. Any alien who is provided a hearing under section 1229a of this title pursuant to this paragraph may thereafter obtain judicial review of any resulting final order of removal pursuant to subsection (a)(1).

(5) Scope of inquiry

In determining whether an alien has been ordered removed under section 1225(b)(1) of this title, the court’s inquiry shall be limited to whether such an order in fact was issued and whether it relates to the petitioner. There shall be no review of whether the alien is actually inadmissible or entitled to any relief from removal.“

(https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title8-section1252&num=0&edition=prelim)