In einem der zahlreichen Rechtsstreite, die wegen der Politik der Trump-Regierung geführt werden, entschied der US-Supreme Court kurz vor Mitternacht von Freitag zu Samstag MESZ mit 5 : 4 Stimmen vorläufig für die Regierungen. Die Nachrichtenagentur AP beschreibt den Streitgegenstand wie folgt: „cut [of] hundreds of millions of dollars in teacher-training money as part of its anti-DEI [Diversity, Equity and Inclusion] efforts“ (https://apnews.com/article/supreme-court-teacher-training-cuts-trump-a400126052c736d262c143bf994b8dda)

Politico schreibt zum Streitgegenstand:

„The programs at issue in the Supreme Court’s ruling were created by Congress to recruit and train teachers to work in ‚underserved‘ communities and to seek out educators from ‚underrepresented populations‘ and ‚who reflect the communities in which they will teach.‘

One of the programs, the Teacher Quality Partnership, was created in 2008 under President George W. Bush. The other, the Supporting Effective Educator Development program, was authorized by Congress in 2015, under President Barack Obama.“

(Gosh Gerstein, Supreme Court, in a win for Trump, lets admin cancel $65M in teaching grants; https://www.politico.com/news/2025/04/04/supreme-court-ruling-education-grants-00273427)

I. Die angegriffenen District Court-Entscheidungen

Vorläufig außer Vollzug gesetzt wurden vom Supreme Court diese (ebenfalls bloß vorläufigen) Entscheidungen des District Court für den District (in dem Fall: = Bundesstaat) Massachusetts:

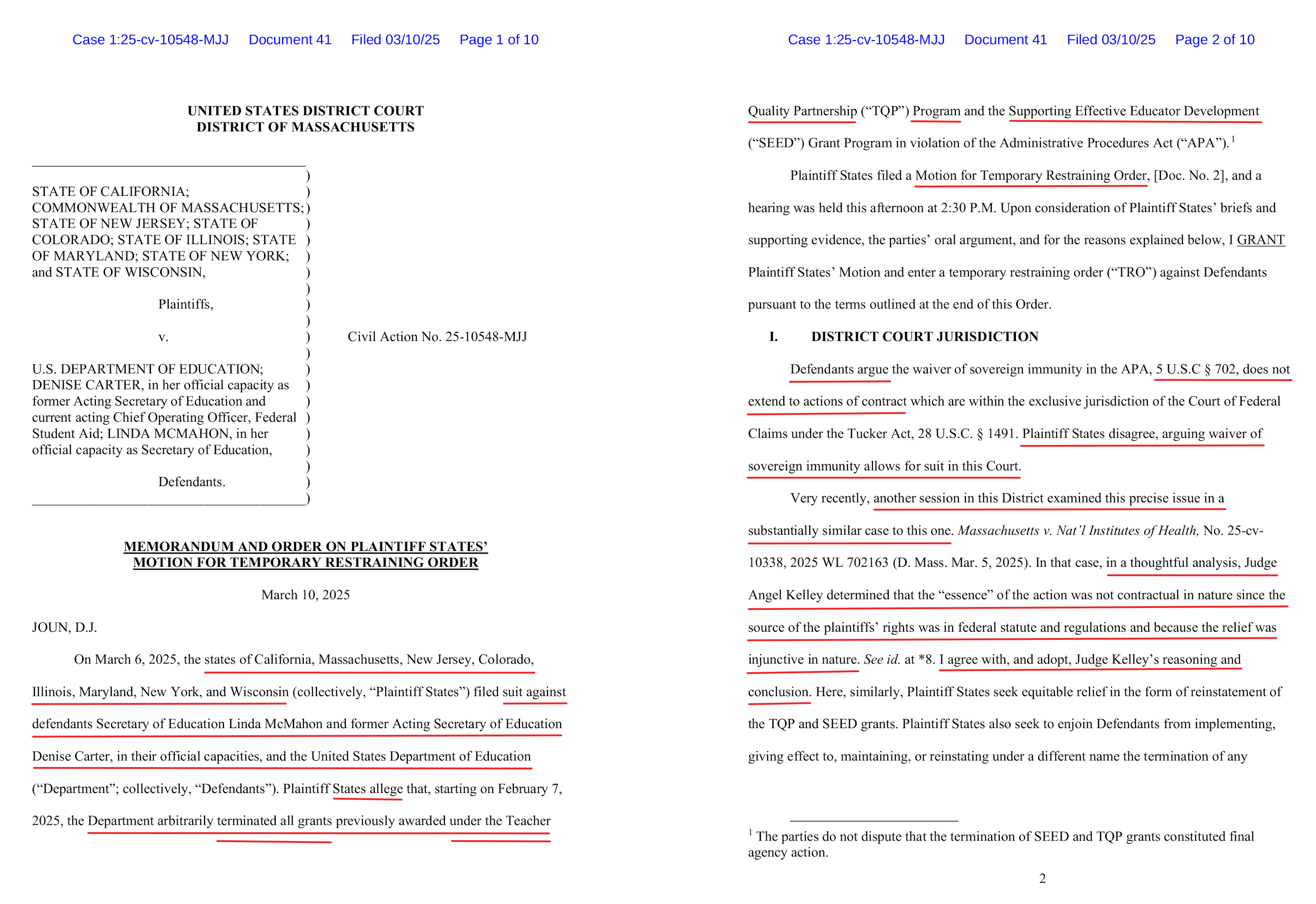

1. Die District Court-Entscheidung vom 10. März 2025

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.281668/gov.uscourts.mad.281668.41.0_2.pdf (10 Seiten)

Wie anhand des Anfangs von Abschnitt I. der Entscheidungen zu erkennen, dreht sich der Streit um die gerichtliche Zuständigkeit (und darum dreht sich auch die Supreme Court-Entscheidung von gestern [siehe unten Abschnitt IV. zwischen den ersten beiden Trennlinien]) vor allem um die Frage, ob gem. 5 U.S.C § 702 der District Court oder aber gem. 28 U.S.C. § 1491 der Court of Federal Claims zuständig ist.

Diese Zuständigkeits-Frage mag als „formell“ bezeichnet werden; aber die Form ist wesentlich (LW 38, 134), wie ein Berufsrevolutionär vom Anfang des 20. Jahrhundert, der im Ausbildungsberuf Jurist war, sagte. Zuständigkeits-Fragen sind keine Kleinigkeit – weder, wenn es um die Zuständigkeit von Verwaltungsbehörden; noch, wenn es um die Zuständigkeit von Gerichten geht. Um deutsche Beispiele zu geben: Es ist nicht egal, ob die Polizei oder eine Datenschutzbehörde zuständig ist und entscheidet; es ist nicht egal, ob ein Umwelt- oder ein Wirtschaftsministerium zuständig ist und entscheidet; es ist nicht egal, ob ein Strafrichter in Sachsen oder eine Strafrichterin in Bremen zuständig ist und entscheidet; es ist nicht egal, ob eine Zivilrechts-Abteilung eines Amtsgerichts oder ein Arbeitsgericht zuständig ist und entscheidet. – Und deshalb ist es auch nicht egal, ob eine unzuständige Behörde bzw. ein unzuständiges Gericht entscheidet – also sich Kompetenzen anmaßt, die sie oder es nicht hat.

5 U.S.C § 702 bestimmt:

„§702. Right of review

A person suffering legal wrong because of agency action, or adversely affected or aggrieved by agency action within the meaning of a relevant statute, is entitled to judicial review thereof. An action in a court of the United States seeking relief other than money damages and stating a claim that an agency or an officer or employee thereof acted or failed to act in an official capacity or under color of legal authority shall not be dismissed nor relief therein be denied on the ground that it is against the United States or that the United States is an indispensable party. The United States may be named as a defendant in any such action, and a judgment or decree may be entered against the United States: Provided, That any mandatory or injunctive decree shall specify the Federal officer or officers (by name or by title), and their successors in office, personally responsible for compliance. Nothing herein (1) affects other limitations on judicial review or the power or duty of the court to dismiss any action or deny relief on any other appropriate legal or equitable ground; or (2) confers authority to grant relief if any other statute that grants consent to suit expressly or impliedly forbids the relief which is sought.“

(https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title5-section702&num=0&edition=prelim; Hv. hinzugefügt)

und 28 U.S.C. § 1491 lautet:

„§1491. Claims against United States generally; actions involving Tennessee Valley Authority

(a)(1) The United States Court of Federal Claims shall have jurisdiction to render judgment upon any claim against the United States founded either upon the Constitution, or any Act of Congress or any regulation of an executive department, or upon any express or implied contract with the United States, or for liquidated or unliquidated damages in cases not sounding in tort. For the purpose of this paragraph, an express or implied contract with the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Navy Exchanges, Marine Corps Exchanges, Coast Guard Exchanges, or Exchange Councils of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration shall be considered an express or implied contract with the United States.

(2) To provide an entire remedy and to complete the relief afforded by the judgment, the court may, as an incident of and collateral to any such judgment, issue orders directing restoration to office or position, placement in appropriate duty or retirement status, and correction of applicable records, and such orders may be issued to any appropriate official of the United States. In any case within its jurisdiction, the court shall have the power to remand appropriate matters to any administrative or executive body or official with such direction as it may deem proper and just. The Court of Federal Claims shall have jurisdiction to render judgment upon any claim by or against, or dispute with, a contractor arising under section 7104(b)(1) of title 41, including a dispute concerning termination of a contract, rights in tangible or intangible property, compliance with cost accounting standards, and other nonmonetary disputes on which a decision of the contracting officer has been issued under section 6 1 of that Act.

(b)(1) Both the Unites 2 States Court of Federal Claims and the district courts of the United States shall have jurisdiction to render judgment on an action by an interested party objecting to a solicitation by a Federal agency for bids or proposals for a proposed contract or to a proposed award or the award of a contract or any alleged violation of statute or regulation in connection with a procurement or a proposed procurement. Both the United States Court of Federal Claims and the district courts of the United States shall have jurisdiction to entertain such an action without regard to whether suit is instituted before or after the contract is awarded.

(2) To afford relief in such an action, the courts may award any relief that the court considers proper, including declaratory and injunctive relief except that any monetary relief shall be limited to bid preparation and proposal costs.

(3) In exercising jurisdiction under this subsection, the courts shall give due regard to the interests of national defense and national security and the need for expeditious resolution of the action.

(4) In any action under this subsection, the courts shall review the agency’s decision pursuant to the standards set forth in section 706 of title 5.

(5) If an interested party who is a member of the private sector commences an action described in paragraph (1) with respect to a public-private competition conducted under Office of Management and Budget Circular A–76 regarding the performance of an activity or function of a Federal agency, or a decision to convert a function performed by Federal employees to private sector performance without a competition under Office of Management and Budget Circular A–76, then an interested party described in section 3551(2)(B) of title 31 shall be entitled to intervene in that action.

(6) Jurisdiction over any action described in paragraph (1) arising out of a maritime contract, or a solicitation for a proposed maritime contract, shall be governed by this section and shall not be subject to the jurisdiction of the district courts of the United States under the Suits in Admiralty Act (chapter 309 of title 46) or the Public Vessels Act (chapter 311 of title 46).

(c) Nothing herein shall be construed to give the United States Court of Federal Claims jurisdiction of any civil action within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court of International Trade, or of any action against, or founded on conduct of, the Tennessee Valley Authority, or to amend or modify the provisions of the Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933 with respect to actions by or against the Authority.“

(https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title28-section1491&num=0&edition=prelim; Hv. hinzugefügt)

2. Die District Court-Entscheidung vom 24. März 2025

„ELECTRONIC ORDER entered On March 6, 2025, Plaintiff States filed suit against Defendants alleging that the Department had arbitrarily terminated grants previously awarded under the TQP and SEED grant programs in violation of the APA. Doc. No. 1 . Plaintiff States simultaneously filed a Motion for TRO as to the grant terminations, Doc. No. 2, which was heard and granted on March 10, 2025, Doc. No. 41. I entered an expedited briefing schedule as to a preliminary injunction, which is now complete, and a hearing is set for Friday, March 28, 2025, at 2:00 PM. Doc. No. 52. In the meantime, the TRO is set to expire today, March 24, 2025. Plaintiff States have moved to extend the TRO, Doc. No. 74; Defendants have opposed, Doc. No. 78. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 65(b)(2) provides that a TRO ‚expires at the time after entry—not to exceed 14 days—that the court sets, unless before that time the court, for good cause, extends it for a like period or the adverse party consents to a longer extension.‘ Here, Defendants do not so consent; however, good cause warrants extending the duration of the TRO until I have had a chance to rule on the preliminary injunction request. Given the complexity of the issues before me, as well as the wide-reaching and irreparable harm likely to be caused to Plaintiff States in the absence of injunctive relief, “[i]t is important… that the status quo not be altered and the public interest not be irreparably injured while these issues are addressed.” Bos. & Maine Corp. v. United Transp. Union, 110 F.R.D. 322, 330 (D. Mass. 1986). The expedited briefing and hearing schedule reflects my intent that the TRO be temporary and short. Accordingly, Plaintiff States’ Motion to Extend TRO, Doc. No. 74, is GRANTED. The duration of the TRO is extended until the date of my decision on the preliminary injunction, not to exceed April 7, 2025. (SP)“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69711499/state-of-california-v-us-department-of-education/#entry-79; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

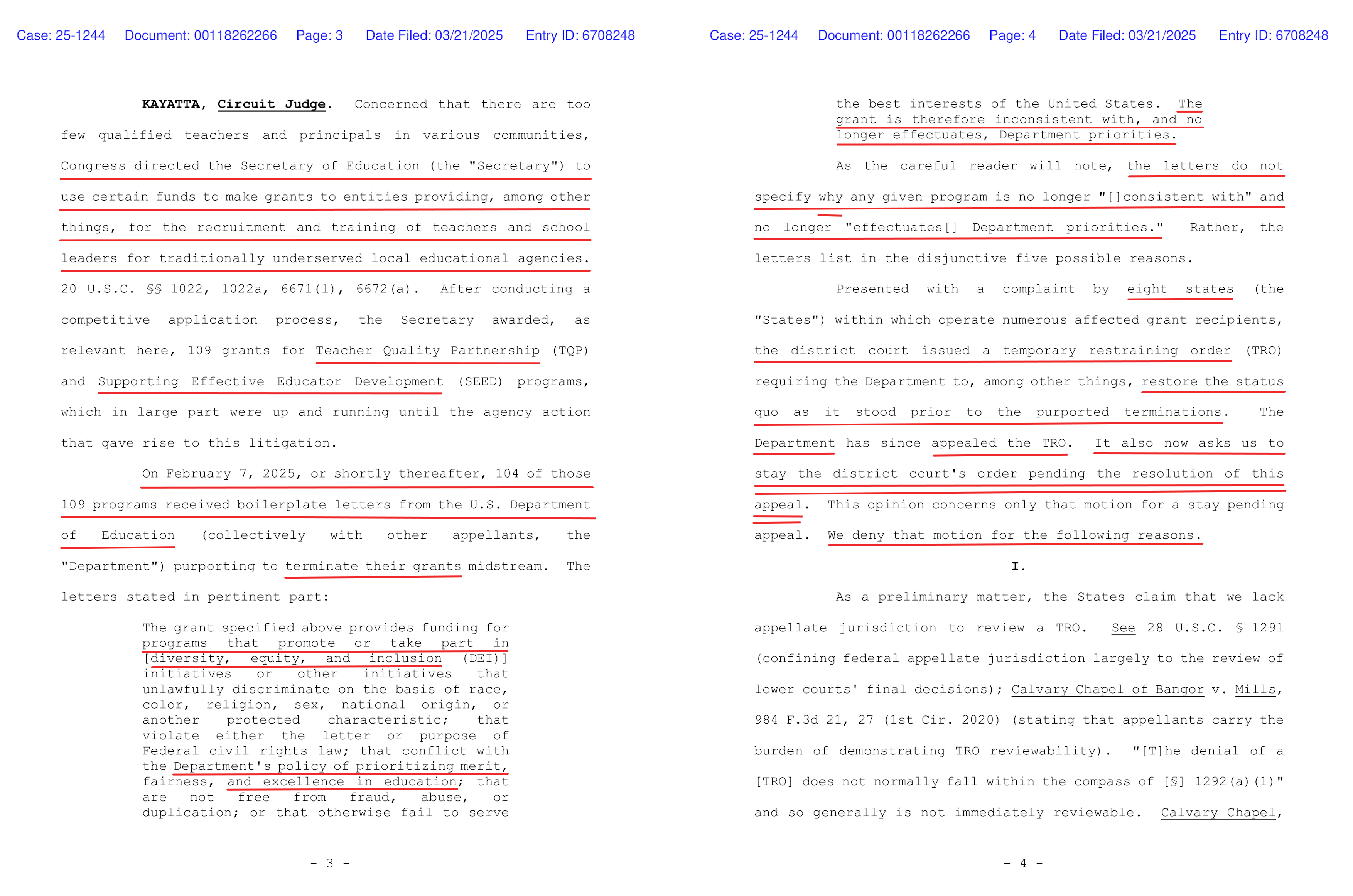

II. Die Appeals Court-Entscheidung, die die Außervollzug-Setzung der District Court-Entscheidungen ablehnte, vom 21. März 2025

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca1.52604/gov.uscourts.ca1.52604.00108262266.0_1.pdf (17 Seiten)

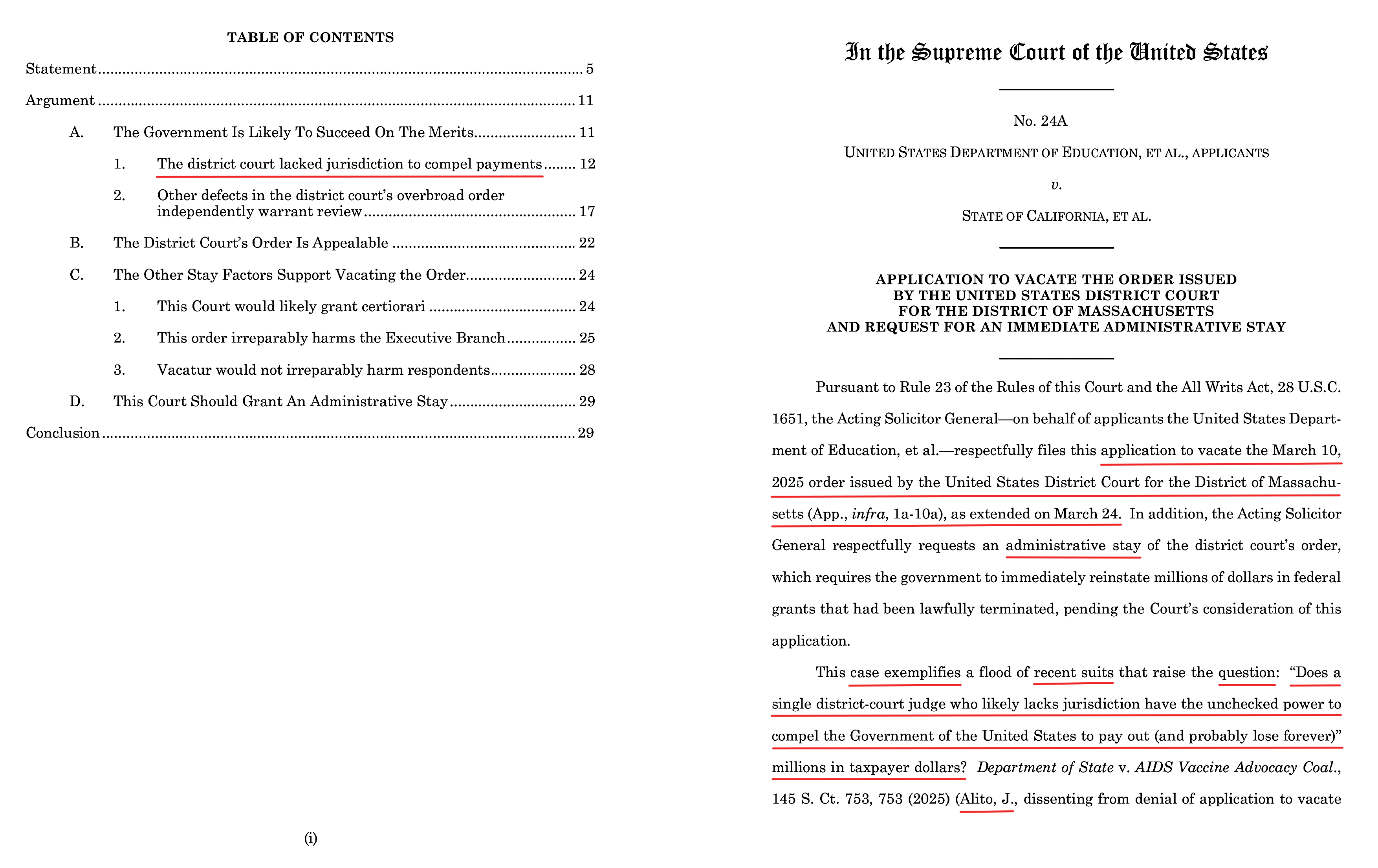

III. Die Schriftsätze für das Supreme Court-Verfahren

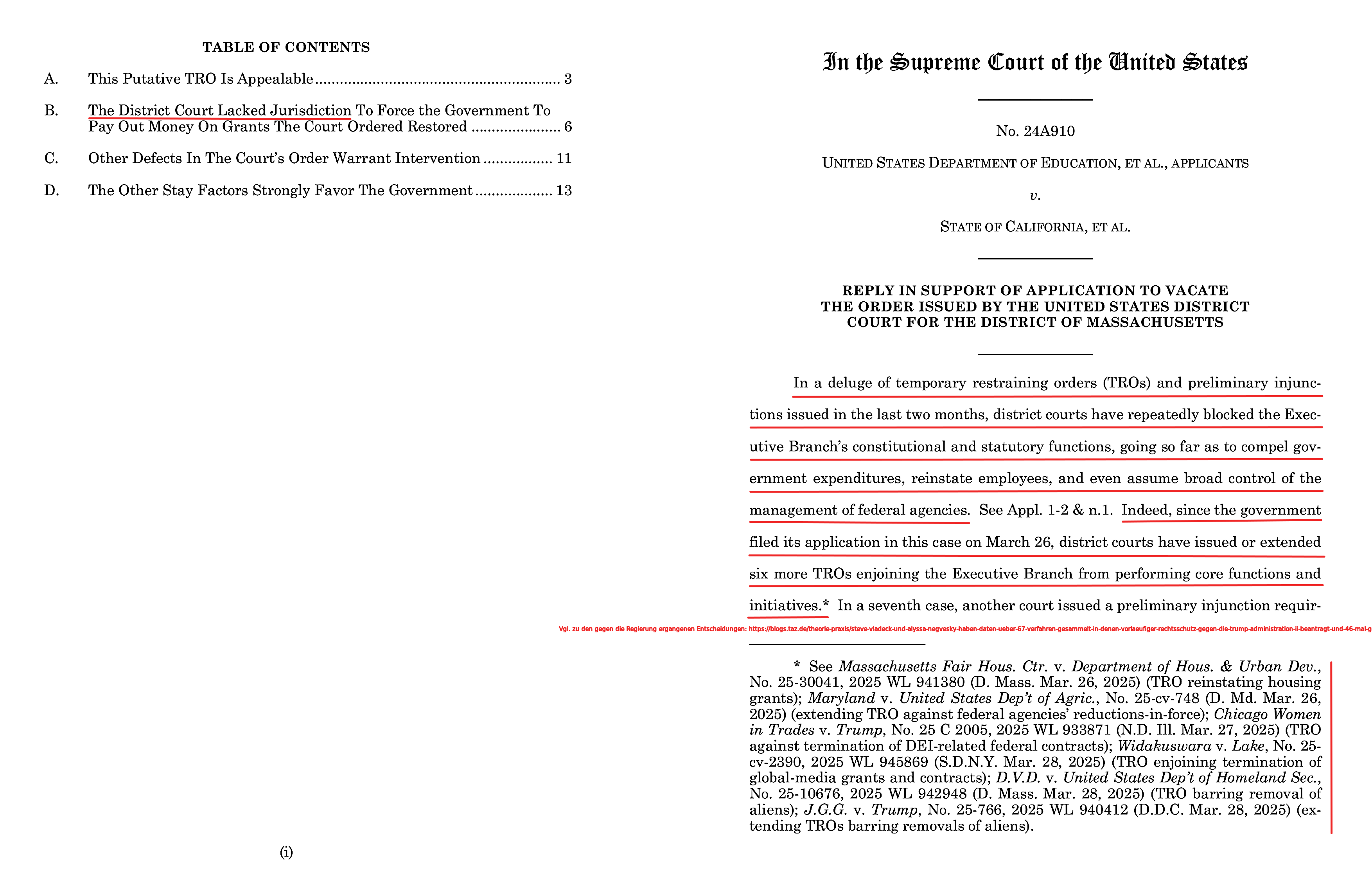

1. Der Antrag der Regierung vom 26.03.2025

https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/24/24A910/353030/20250326114427721_24A%20Ed%20v.%20CA%20appl.pdf (33 Seiten + 38 Seiten Anlagen)

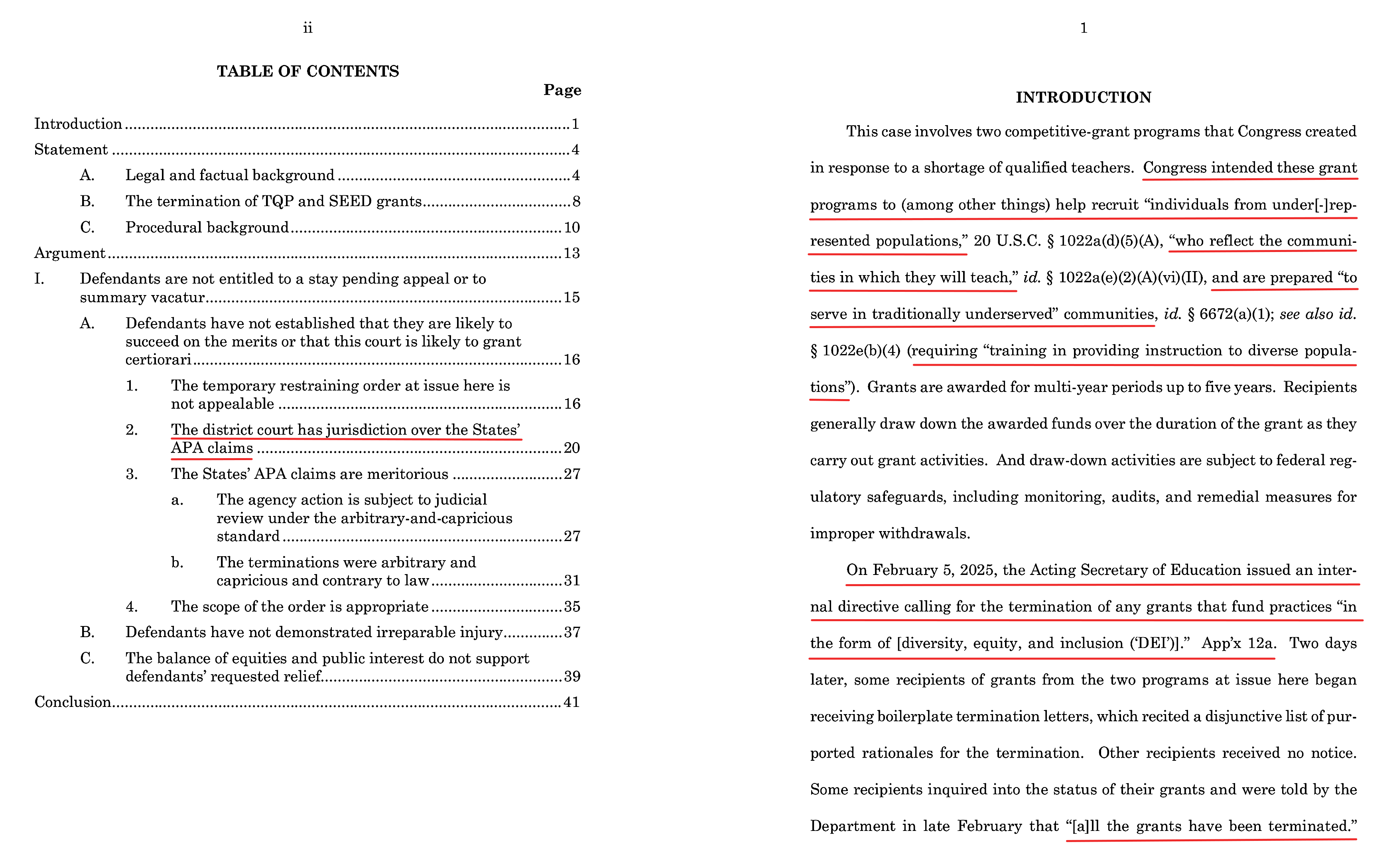

2. Die Antwort der acht vor dem District Court klagenden Bundesstaaten vom 28.03.2025

3. Die Rück-Antwort der Regierung vom 31.03.2025

IV. Die Supreme Court-Entscheidung von Freitag, den 4. April 2025

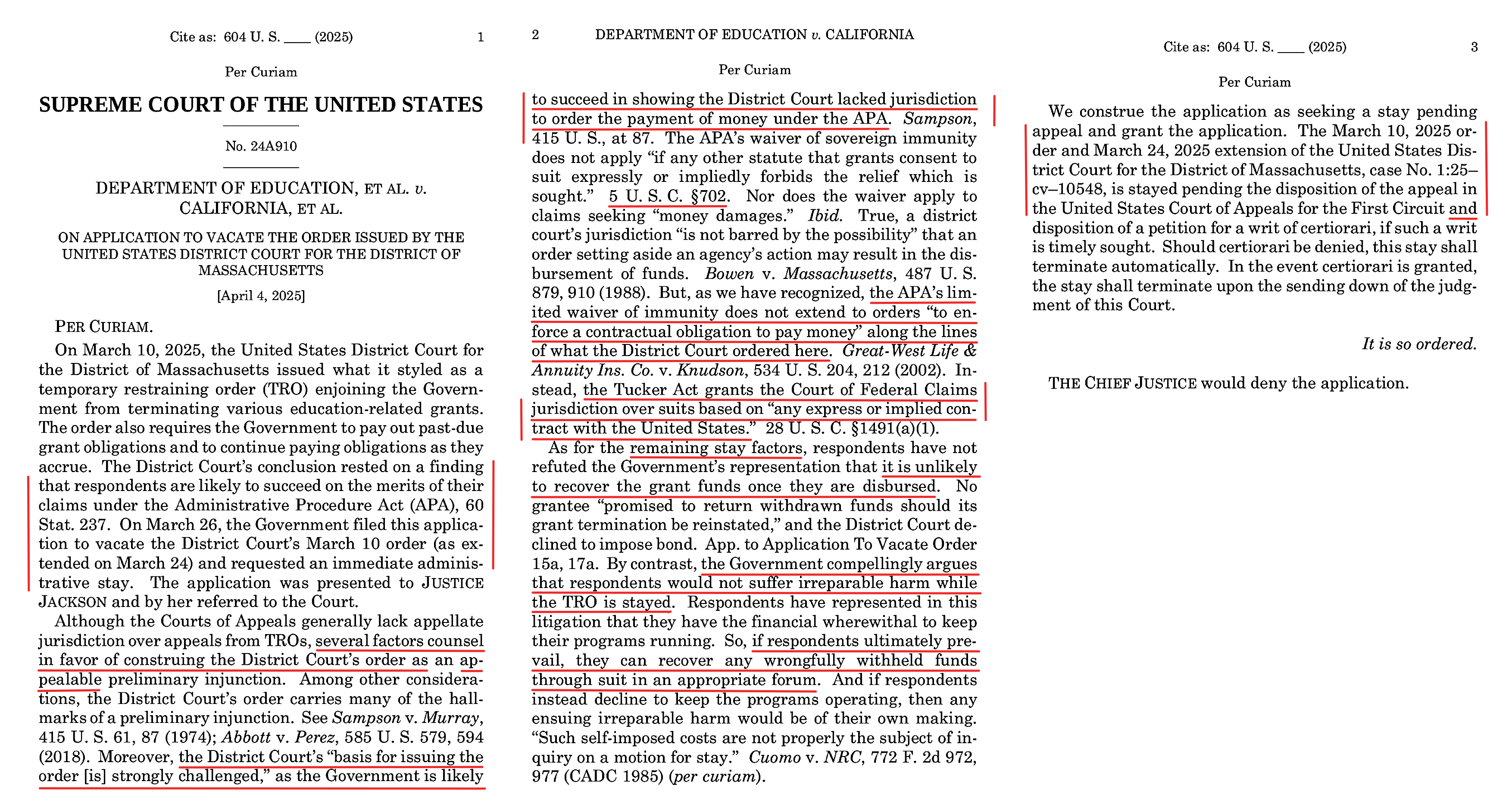

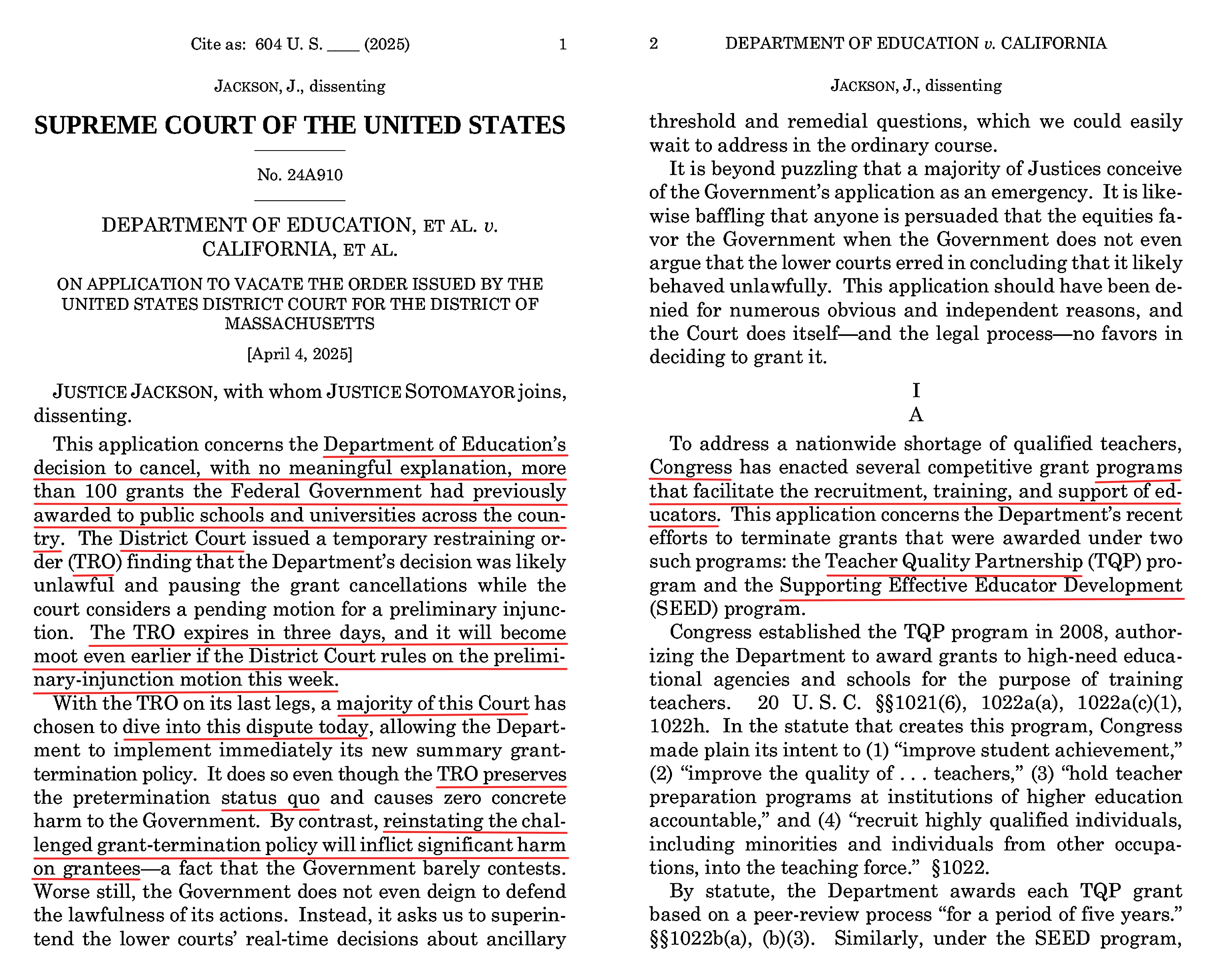

1. Die drei Voten

Die Datei mit der gestrigen Entscheidung umfaßt 22 Seiten:

Auf S. 1 bis 3 befindet sich das Mehrheitsvotum,

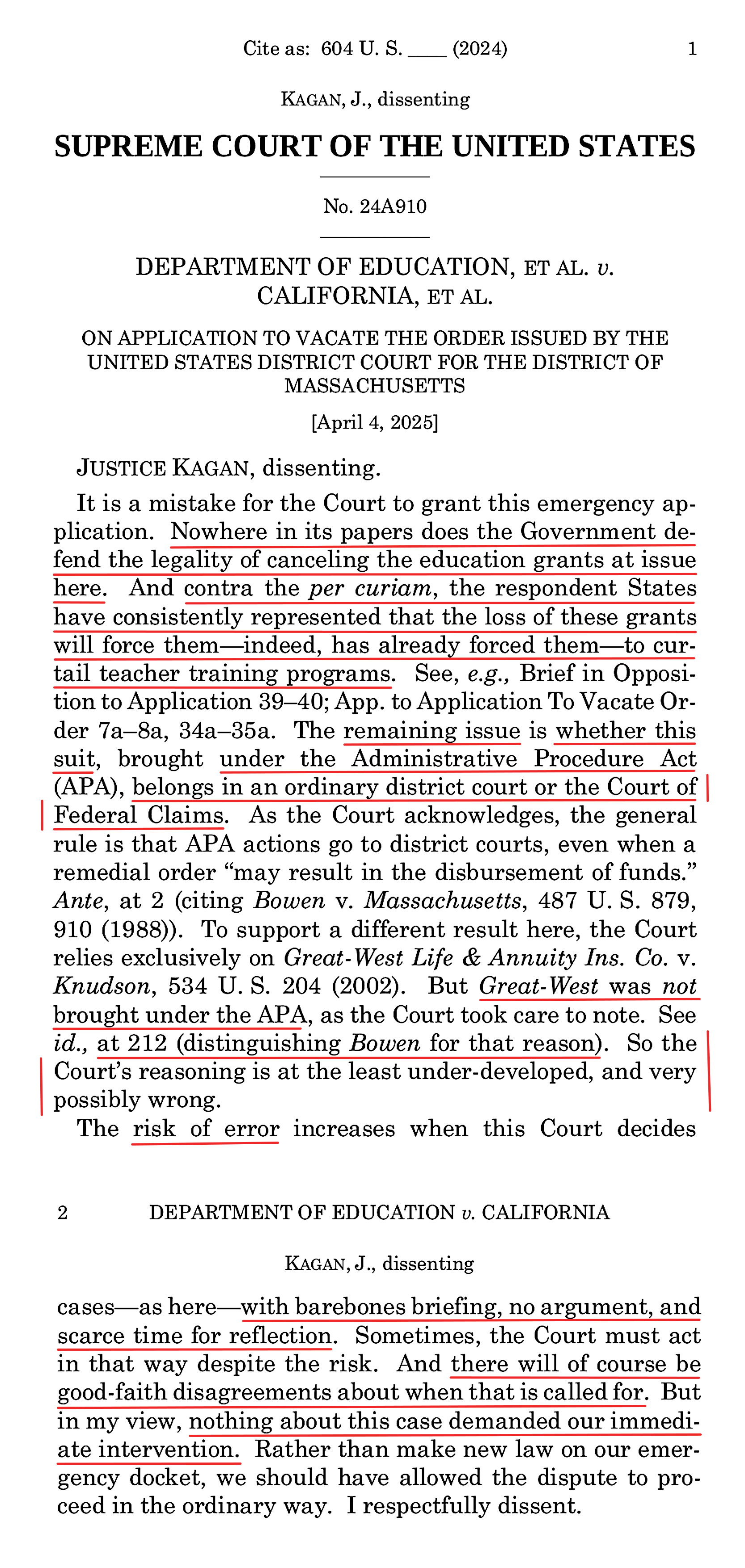

auf S. 4 – 5 ein disstentierendes Votum der – von Obama nominierten – Richterin Kagan.

auf S. 6 – 22 befindet sich ein disstentierendes Votum der – von Biden nominierten – Richterin Jackson, dem sich die – von Obama nominierte – Richterin Sotomayor anschloß.

Außerdem stimmte der – von George W. Bush nominierte – Vorsitzende des Supreme Court (ohne Begründung) gegen die gestrige Entscheidung.

2. Argumente zur Zuständigkeits-Frage

Die Mehrheit sagt also zur Zuständigkeits-Frage:

„the District Court’s ‚basis for issuing the order [is] strongly challenged,‘ as the Government is likely to succeed in showing the District Court lacked jurisdiction to order the payment of money under the APA. Sampson, 415 U. S., at 87. The APA’s waiver [*] of sovereign immunity [**] does not apply ‚if any other statute that grants consent to suit expressly or impliedly forbids the relief which is sought.‘ 5 U. S. C. §702. Nor does the waiver apply to claims seeking ‚money damages.‘ Ibid. True, a district court’s jurisdiction ‚is not barred by the possibility‘ that an order setting aside an agency’s action may result in the disbursement of funds. Bowen v. Massachusetts, 487 U. S. 879, 910 (1988). But, as we have recognized, the APA’s limited waiver of immunity does not extend to orders ‚to enforce a contractual obligation to pay money” along the lines of what the District Court ordered here. Great-West Life & Annuity Ins. Co. v. Knudson, 534 U. S. 204, 212 (2002). Instead, the Tucker Act grants the Court of Federal Claims jurisdiction over suits based on ‚any express or implied contract with the United States.‘ 28 U. S. C. §1491(a)(1).“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 1 f.; *-Fußnoten und Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Richterin Kagan ist bezüglich dieser Argumente zwar skeptisch, aber hält sie auch nicht für rundheraus unzutreffend: Sie sagt zu dem „issue […] whether this suit, brought under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), belongs in an ordinary district court or the Court of Federal Claims“ Folgendes:

„As the Court [= Die Supreme Court-Mehrheit] acknowledges, the general rule is that APA actions go to district courts, even when a remedial order ‚may result in the disbursement of funds.‘ Ante, at 2 (citing Bowen v. Massachusetts, 487 U. S. 879, 910 (1988)). To support a different result here, the Court relies exclusively on Great-West Life & Annuity Ins. Co. v. Knudson, 534 U. S. 204 (2002). But Great-West was not brought under the APA, as the Court took care to note. See id., at 212 (distinguishing Bowen for that reason). So the Court’s reasoning is at the least under-developed, and very possibly wrong.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 4 der Datei; Hv. + Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Wenn vielleicht ein unzuständiges Gericht entschieden hat, ist es dann (zwangsläufig) verkehrt, diese Gerichtsentscheidung erst einmal außer Vollzug zu setzen, bis geklärt ist, ob das Gericht zuständig ist?

Die Richterinnen Jackson und Sotomayer beschäftigen sich bloß in einer Fußnote auf der letzten Seite ihres Votums mit der Zuständigkeits-Frage:

„Without oral argument and with less than one week’s worth of deliberation, the Court now has determined that, at least in this context, restoring the grants at issue might qualify as an order to ‚›enforce a contractual obligation to pay money‹‘ such that it is the Court of Federal Claims, rather than the District Court, that has jurisdiction over the Plaintiff States’ challenge. Ante, at 2 (quoting Great-West Life & Annuity Ins. Co. v. Knudson, 534 U. S. 204, 212 (2002)). Even assuming that Great-West has any bearing on this issue, the majority’s characterization of the relief granted by the District Court is dubious given what the Plaintiff States actually say in their complaint about the legal problem and the relief they are requesting. See ECF Doc. 1, pp. 46–47, 51–52; see also Bowen v. Massachusetts, 487 U. S. 879, 893 (1988) (‚The fact that a judicial remedy may require one party to pay money to another is not a sufficient reason to characterize the relief as ›money damages‹‘). And the majority does not dispute the ‚basic reality‘ that some APA challenges to grant-related administrative action may proceed in district court, even if they have as their ’natural consequence … the release of funds to the plaintiff down the road.‘ Department of State v. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, 604 U. S. ___, ___ (2025) (ALITO , J., dissenting from denial of application) (slip op., at 6).“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 22 der Datei, FN 7; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

3. Vergleich mit der kürzlichen Entscheidung des Supreme Court wegen der Sperrung von „Entwicklungshilfe“-Mittel

In einem kürzlichen Verfahren wegen der Sperrung von „Entwicklungshilfe“-Mittel hatte der Supreme Court die dort von der Trump-Regierung beantragte außer Vollzug-Setzung der untergerichtlichen Entscheidung mit 5 : 4 Stimmen abgelehnt (siehe taz-Blogs vom 05.03.2025). Die damalige Minderheit argumentierte damals:

„The Government has shown a likelihood of success on the merits of its argument that sovereign immunity deprived the District Court of jurisdiction to enter its enforcement order. Sovereign immunity may be waived, but ‚[t]o sustain a claim that the Government is liable for awards of monetary damages, the waiver of sovereign immunity must extend unambiguously to such monetary claims.‘ Lane v. Peña, 518 U. S. 187, 192 (1996). Attempting to satisfy this strict requirement, respondents point to the APA’s waiver of sovereign immunity for certain actions ’seeking relief other than money damages.‘ 5 U. S. C. §702. That language, as we have explained, distinguishes ‚between specific relief,‘ which is permitted under the APA, and ‚compensatory, or substitute, relief,‘ which is not. Department of Army v. Blue Fox, Inc., 525 U. S. 255, 261 (1999). But the relief here more closely resembles a compensatory money judgment rather than an order for specific relief that might have been available in equity. See Great-West Life & Annuity Ins. Co. v.Knudson, 534 U. S. 204, 210–211 (2002) (‚[A]n injunction to compel the payment of money past due under a contract, or specific performance of a past due monetary obligation, was not typically available in equity‘). Sovereign immunity thus appears to bar the sort of compensatory relief that the District Court ordered here. Hoping to escape that conclusion, respondents point to Bowen v. Massachusetts, 487 U. S. 879 (1988). In that case, we held that the APA’s waiver of sovereign immunity covered a District Court’s judgment reversing a final order of the Secretary of Health and Human Services refusing to reimburse Massachusetts for certain Medicaid expenditures. Unlike the District Court’s order here, that ‚judgment did not purport to … order that any payment be made‘ by the United States. Id., at 888. Rather, Bowen simply recognized a basic reality of APA review: after a court sets aside an agency action, a natural consequence may be the release of funds to the plaintiff down the road. Indeed, we have since clarified that ‚Bowen has no bearing on the unavailability of an injunction to enforce a contractual obligation to pay money past due’—the sort of relief that appears to have been ordered here. Knudson, 534 U. S., at 212. The District Court, however, failed to mention (much less reckon with) Bowen or Knudson before plowing ahead with its $2 billion order. Nor did it take account of our previous suggestion that the proper remedy for an agency’s recalcitrant failure to pay out may be to ’seek specific sums already calculated‘ and ‚past due‘ in the Court of Federal Claims. Maine Community Health Options v. United States, 590 U. S. 296, 327 (2020); Bowen, 487 U. S., at 890, n. 13 (invoking the First Circuit’s suggestion that if an agency ‚›persist[s] in withholding reimbursement for reasons inconsistent with our decision‹ under the APA, the ‚›remedy would be a suit for money past due under the Tucker Act in the Claims Court‹‘). The most that can be said is that in the District Court’s denial of the Government’s motion for a stay pending appeal, it cited but did not analyze a handful of cases echoing Bowen’s discussion of the APA’s conscribed waiver of sovereign immunity. One might expect more care from a federal court before it so blithely discards ’sovereign dignity.‘ Alden v. Maine, 527 U. S. 706, 715 (1999).“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a831_3135.pdf, S. 5 oben bis 7 oben; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Die damalige Minderheit bildeten zwei von Trump nominierte Richter (Neil Gorsuch und Brett Kavanaugh) und ein von George H. W. Bush nominierter Richter (Clarence Thomas) sowie der – neben dem Vorsitzenden Roberts – zweite von George W. Bush nominierte Richter (Samuel Alito, der das Minderheitsvotum verfaßte).

Die von Trump nominierte Richterin, Amy Coney Barrett gehörte damals zur Mehrheit, und sie gehört jetzt wieder zur Mehrheit. Warum sie sozusagen das Lager wechselte und dadurch die Mehrheit drehte, läßt, sich schwer sagen. Denn die damalige Mehrheit (also auch Barrett) hatte damals praktisch keine Begründung für ihre Entscheidung gegeben.

4. Drei Richterinnen bestreiten Zuständigkeit des Supreme Court

Daß formelle, hier: Zuständigkeitsfragen keine Nebensächlichkeiten sind, wird dadurch unterstrichen, daß diesmal drei Richterinnen den Supreme Court seinerseits für unzuständig halten. Denn grundsätzlich sind bloße Temporary Restraining Orders (TRO), weil sie ohnehin nur eine sehr kurze Geltungsdauer haben, nicht anfechtbar, wie auch die jetzige Supreme Court-Mehrheit zugesteht. Die Mehrheit ist trotzdem der Ansicht, daß

„several factors counsel in favor of construing the District Court’s order as an appealable preliminary injunction. Among other considerations, the District Court’s order carries many of the hallmarks of a preliminary injunction. See Sampson v. Murray, 415 U. S. 61, 87 (1974); Abbott v. Perez, 585 U. S. 579, 594 (2018). Moreover, the District Court’s ‚basis for issuing the order [is] strongly challenged,” as the Government is likely to succeed in showing the District Court lacked jurisdiction to order the payment of money under the APA.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 1 f. der Datei)

Mit Letzterem sind wir dann wieder bei der gerade schon erörterten Frage nach der Zuständigkeit des District Court.

Die Richterin Jackson argumentiert demgegenüber (mit Zustimmung von Richterin Sotomayor), was die Zuständigkeit des Supreme Court bzw. die Anfechtbarkeit der TRO anbelangt:

„First and foremost, the Government’s application should have been swiftly denied because this Court lacks jurisdiction over this interlocutory order. It is clear beyond cavil that, ordinarily, ‚orders granting . . . temporary restraining …“

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 11 und 12 der Datei

Und das Votum von Richterin Kagan war ja oben schon in Gänze zu lesen; ihre Begründung, warum der Supreme Court den Regierungsantrag hätte ablehnen sollen, beruht vor allem darauf, daß sie nicht überzeugt ist, daß der District Court tatsächlich unzuständig ist und sich der Supreme Court ihres Erachtens hätte raushalten sollten, solange diese Frage weiter vor den unteren Gerichten diskutiert wird:

„we should have allowed the dispute to proceed in the ordinary way“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 5 der Datei)

Außerdem betont sie, daß ihres Erachtens auch das Gericht, daß sich am Ende als zuständig erweist, wahrscheinlich gegen die Regierung und für die klagenden Bundesstaaten entscheiden wird müssen:

„Nowhere in its papers does the Government defend the legality of canceling the education grants at issue here.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 4)

5. Wessen Schaden?

Die dritte Differenz zwischen der Supreme Court-Mehrheit und den drei Richterinnen, die abweichende Voten veröffentlicht haben, betrifft die Frage, welche Seite den größeren Schaden zu befürchten hat.

Die Gerichts-Mehrheit sagt: Die respondents (also die AntragsgegnerInnen des Supreme Court-Verfahrens = klagenden Bundesstaaten des District Court-Verfahrens)

„have not refuted the Government’s representation that it is unlikely to recover the grant funds once they are disbursed. No grantee ‚promised to return withdrawn funds should its grant termination be reinstated,‘ and the District Court declined to impose bond. App. to Application To Vacate Order 15a, 17a. By contrast, the Government compellingly argues that respondents would not suffer irreparable harm while the TRO is stayed. Respondents have represented in this litigation that they have the financial wherewithal to keep their programs running. So, if respondents ultimately prevail, they can recover any wrongfully withheld funds through suit in an appropriate forum. And if respondents instead decline to keep the programs operating, then any ensuing irreparable harm would be of their own making. ‚Such self-imposed costs are not properly the subject of inquiry on a motion for stay.‘ Cuomo v. NRC, 772 F. 2d 972, 977 (CADC 1985) (per curiam).

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 2 der Datei; Hyperlink hinzugefügt „15a“ und „17a“ sind Seiten der Anlagen)

Richterin Kagan ist demgegenüber der Ansicht:

„the respondent States have consistently represented that the loss of these grants will force them—indeed, has already forced them—to curtail teacher training programs. See, e.g., Brief in Opposition to Application 39–40; App. to Application To Vacate Order 7a–8a, 34a–35a.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a910_f2bh.pdf, S. 4)

In dem Votum von Richterin Jackson (und Sotomayor) geht es – wie oben bereits zu lesen – auf S. 1 unten und 2 (= S. 6 unten und 7 der Datei) sowie außerdem von S. 8 unten – 11 oben (= S. 13 unten – 16 oben der Datei) sowie S. 14 oben – 16 (= S. 19 – 21 oben der Datei) um die Schadens-Frage.

V. Prof. Steve Vladeck zu der Entscheidung

Gestern – bereits kurz nach Bekanntwerden der Entscheidung – hat sich Georgetown-University Jura-Prof. Steve Vladeck bei Lawfare Live: Trials of the Trump Administration zu der Entscheidung geäußert.

https://youtu.be/TucpbJt-LvQ?t=3101 (ab ca. Min. 51:41 – ca. 56:49 sowie bereits irgendwo deutlich früher);

vgl. https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/lawfare-live–trials-of-the-trump-administration–april-4.

NACHTRAG:

Steve Vladeck, Three (Quick) Reactions to the Education Grants Ruling

https://www.stevevladeck.com/p/137-three-quick-reactions-to-the

„folks looking to today’s ruling as a sign, one way or the other, of everything that the Court is going to do in Trump cases, may well end up disappointed—for better or for worse.“

VI. Wie es weitergeht

Wie es weitergeht, werden wir wahrscheinlich Mitte / Ende der kommenden Woche erfahren. Die klagenden Bundesstaaten beantragten nach der Supreme Court-Entscheidung beim District Court die Erlaubnis,

„to submit a supplemental filing by no later than Thursday, April 10, 2025, addressing the matters raised by the Supreme Court’s decision.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mad.281668/gov.uscourts.mad.281668.87.0.pdf, S. 1)

Dieser entschied – auch noch am Freitagabend US-Zeit:

„In light of the Supreme Court’s decision in this matter, the parties shall submit any supplemental filings by no later than 5 p.m. on Tuesday, April 8, 2025.“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69711499/state-of-california-v-us-department-of-education/#entry-88)

VII. Um der Klarheit willen

Ich habe keine Überzeugung zur Frage, ob die Supreme Court-Mehrheit oder -Minderheit Recht hat, sondern stelle hier nur Material zusammen, das analysiert werden müßte, um sich eine Überzeugung zu bilden, und benenne die entscheidenden und umstrittenen Fragen.

IIX. Hinweis auf ein ähnliches Verfahren, das noch nicht den Supreme Court erreicht hat

„Another federal judge in Maryland also ordered the Trump administration to continue funding the same types of grants for members of specific education-related groups who filed a separate suit over efforts to terminate the programs.“

(Gosh Gerstein, Supreme Court, in a win for Trump, lets admin cancel $65M in teaching grants; https://www.politico.com/news/2025/04/04/supreme-court-ruling-education-grants-00273427)

Das dortige District Court-Verfahren:

das Appeals Court-Verfahren:

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69840184/state-of-maryland-v-usda/.

[*]

waiver

= „‚act of waiving,‘ 1620s (but in modern use often short for waiver clause); from Anglo-French legal usage of infinitive as a noun (see waive).“ (https://www.etymonline.com/word/waiver)

waive

= „‚deprive of legal protection; remove from a place or condition,‘ from Anglo-French weyver ‚abandon, waive‘ (Old French guever „abandon, give back“), probably from a Scandinavian source akin to Old Norse veifa „to swing about“ (from Proto-Germanic *waif-, from PIE root *weip- ‚to turn, vacillate, tremble ecstatically‘).“ (https://www.etymonline.com/word/waive; vgl. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofindoeuropeanculturejamesmalloryadamsd.q.routledge_254_A/page/607/mode/1up und https://archive.org/details/lexikon-der-indogermanischen-verben/page/671/mode/1up – jeweils s.v. ueip-)

[**]

sovereign immunity

„is a common law doctrine under which a sovereign (e.g., a federal or state government) cannot be sued without its consent. Sovereign immunity in the United States was derived from the British common law, which was based on the idea that the King could do no wrong. In the United States, sovereign immunity typically applies to both the federal government and state government, but not to municipalities. Federal and state governments, however, have the ability to waive their sovereign immunity in whole or in part.“ (https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/sovereign_immunity)