Am Donnerstag, den 3. April wird vor dem Discourt Court für den District of Columbia eine mündliche Verhandlung zur Frage, ob die Trump-Regierung mit den am Samstag, den 15.3. erfolgten Abschiebungen von vermeintlichen Tren de Aragua-Mitgliedern nach El Salvador unter Berufung den Alien Enemies Act eine gültige gerichtliche Anordnung verletzt hat, stattfinden:

„The Court ORDERS that the parties shall appear on April 3, 2025, at 3:00 p.m. for a hearing on the Court’s 47 Order to Defendants to show cause why they did not violate the Court’s Temporary Restraining Orders. Members of the public may attend in person or by telephone. Toll free number: 833-990-9400. Meeting ID: 049550816.“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69741724/jgg-v-trump/?filed_after=&filed_before=&entry_gte=&entry_lte=&order_by=desc#minute-entry-420862452; Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

Vorab – für LeserInnen mit wenig Zeit:

Die Vorgeschichte

Die (mündliche) Anordnung des Gerichts war ziemlich klar:

„So, Mr. Ensign, the first point is that I — that you shall inform your clients of this immediately, and that any plane containing these folks that is going to take off or is in the air needs to be returned to the United States, but those people need to be returned to the United States.

However that’s accomplished, whether turning around a plane or not embarking anyone on the plane or those people covered by this on the plane, I leave to you. But this is something that you need to make sure is complied with immediately.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.20.0_4.pdf, S. 43 [Zeile 11 – 19]; Hv. hinzugefügt)

Die Kläger und Antragsteller des Verfahrens argumentieren in ihrem am Montag bei Gericht eingereichten Schriftsatz:

„Plaintiffs respectfully submit that the Court already possesses the information it needs to conclude that its March 15 oral and written temporary restraining orders were violated. The government has confirmed that ‚two flights

carrying aliens being removed under the AEA departed U.S. airspace before the Court’s minute order of 7:25 PM EDT, and before the Court’s oral statements during the hearing.‘ Decl. of Robert L. Cerna, Acting Field Office Director, ICE (ECF No. 49-1). The government has also confirmed that it is ’not contest[ing] for the purposes of these proceedings that the planes landed abroad, and that the aliens on board were deplaned, after the issuance of the Court’s minute order.‘ Defs. Notice Invoking State Secrets Privilege 7–8 (ECF No. 56) (‚Defs. Notice). These facts, standing alone, establish that the government failed to comply with both of the Court’s orders. See also Pls. Notice Regarding Mar. 19 Order 1–3 (ECF No. 55) (describing additional public details about the flights and submitting declarations refuting the government’s contention that it was not feasible for the planes to return class members to the United States)“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.69.0_1.pdf, S. 1 f. Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Die Regierung argumentierte vorher (am 25.03.2025) in einem Schriftsatz:

„It is well-settled that an oral directive is not enforceable as an injunction.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.58.0_2.pdf, S. 5)

Dieses rechtliche Argument der Regierung ist deshalb wichtig, weil in der späteren schriftlichen Anordnung des Gerichts nichts (Ausdrückliches) bzgl. Umkehr der Flugzeuge steht:

„As discussed in today’s hearing, the Court ORDERS that: 1) Plaintiffs‘ 4 Motion for Class Certification is GRANTED insofar as a class consisting of ‚All noncitizens in U.S. custody who are subject to the March 15, 2025, Presidential Proclamation entitled ›Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of The United States by Tren De Aragua‹ and its implementation‘ is provisionally certified; 2) The Government is ENJOINED from removing members of such class (not otherwise subject to removal) pursuant to the Proclamation for 14 days or until further Order of the Court; […].“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69741724/jgg-v-trump/?filed_after=&filed_before=&entry_gte=&entry_lte=&order_by=desc#minute-entry-419399699)

Am späten Montagabend Ostenküsten-Zeit kam die Antwort der Kläger und Antragsteller auf das rechtliche Regierungs-Argument („an oral directive is not enforceable as an injunction“).

Die beiden Schriftsätze

Sehen wir uns zunächst die einschlägigen Passagen beider Schriftsätze an.

Der Regierungs-Schriftsatz

Hier zunächst der von der Regierung:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.58.0_2.pdf (14 Seiten)

Der Schriftsatz der Kläger und Antragsteller

Und nun der der Kläger und Antragsteller:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.70.0_1.pdf (12 Seiten)

Von der Regierung angeführte Fundstellen

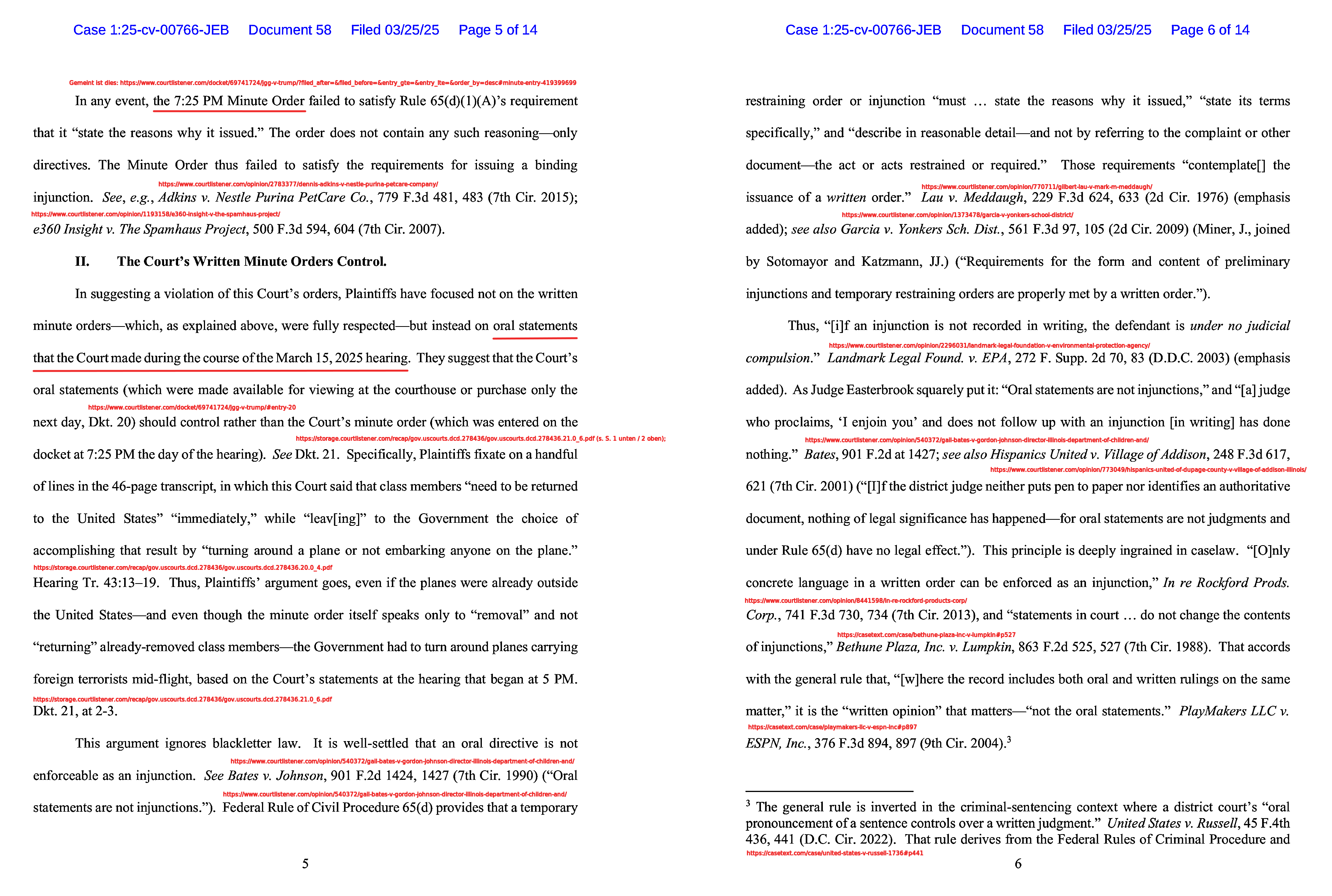

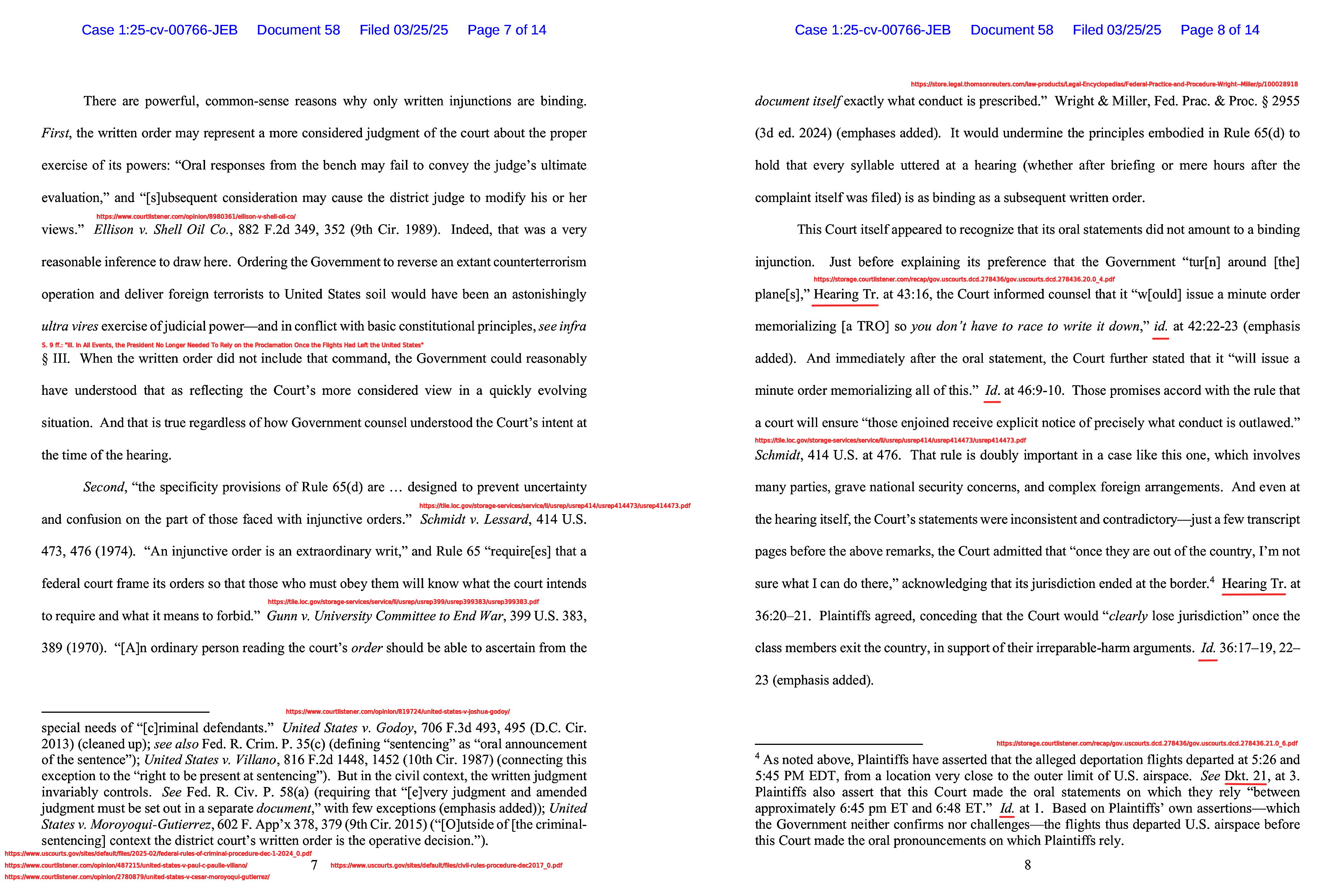

Beginnen wir nun mit dem zweiten Satz des Absatzes, der sich auf S. 5 unten und 6 oben des Regierungs-Schriftsatzes befindet:

„It is well-settled that an oral directive is not enforceable as an injunction. See Bates v. Johnson, 901 F.2d 1424, 1427 (7th Cir. 1990) (‚Oral statements are not injunctions.‘). Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d) provides that a temporary restraining order or injunction ‚must … state the reasons why it issued,‘ ’state its terms specifically,‘ and ‚describe in reasonable detail—and not by referring to the complaint or other document—the act or acts restrained or required.‘ Those requirements ‚contemplate[] the issuance of a written order.‘ Lau v. Meddaugh, 229 F.3d 624, 633 (2d Cir. 1976) (emphasis added); see also Garcia v. Yonkers Sch. Dist., 561 F.3d 97, 105 (2d Cir. 2009) (Miner, J., joined by Sotomayor and Katzmann, JJ.) (‚Requirements for the form and content of preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders are properly met by a written order.‘)“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.58.0_2.pdf, S. 5 unten / 6 oben; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Die Entscheidung Bates v. Johnson

Die erste von der Regierung angeführte Stelle hört sich auch dann, wenn die Sätze um das Zitat herum mitgelesen werden, ziemlich eindeutig an:

„Like the state, we are puzzled by the district judge’s unwillingness to put on paper what he said several times in court. Oral statements are not injunctions. A judge who proclaims ‚I enjoin you‘ and does not follow up with an injunction has done nothing. Eakin v. Continental Illinois National Bank & Trust Co., 875 F.2d 114, 118 (7th Cir.1989); Bethune Plaza, Inc. v. Lumpkin, 863 F.2d 525, 527-28 (7th Cir.1988); Azeez v. Fairman, 795 F.2d 1296, 1297 (7th Cir.1986). Injunctions are not like Islamic divorces, accomplished by intoning a formula thrice in public. Fed.R.Civ.P. 65(d) provides that ‚[e]very order granting an injunction … shall set forth the reasons for its issuance; shall be specific in terms; [and] shall describe in reasonable detail, and not by reference to the complaint or other document, the act or acts sought to be restrained‘. No such ‚order‘ has been issued.

When a judge does not record an injunction or declaratory judgment on a separate document, the defendant is under no judicial compulsion. As we said in Bethune, 863 F.2d at 527, an opinion or statement in court ‚is not itself an order to act or desist; it is a statement of reasons supporting the judgment. The command comes in the separate document entered under Fed.R.Civ.P. 58, which alone is enforceable. There must be a separate document, with a self-contained statement of what the court directs to be done. So if the opinion contains language awarding declaratory relief [or an injunction], but the judgment does not, the opinion has been reduced to dictum; only the judgment need be obeyed.'“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/540372/gail-bates-v-gordon-johnson-director-illinois-department-of-children-and/, Textziffer 18 und 19)

Allerdings ist der 7. Appeals Court nicht der Appeal Court, der dem Discourt Court für den District of Columbia übergeordnet ist und am Ende des Absatzes nach den beiden zitierten Ansätzen – also bei Textziffer 20 – heißt etwas relativierend bzw. einschränkend (at least) u.a.:

„The district judge believed, and reiterated on September 15, that his instructions are oral. As a matter of law, oral instructions are no instructions–at least, not legally binding if a party wishes to put up a fight, as Illinois does.“

(Hv. hinzugefügt)

Allerdings hat die Regierung in dem AEA-Verfahren die weniger weitgehende schriftliche Anordnung des dortigen Richters angefochten und es besteht daher wenig Anlaß anzunehmen, sie wollte die weitergehende mündliche Anordnung akzeptieren. Vielmehr hat sie der mündlichen Anordnung umgehend zu wider gehandelt und dies dem Gericht am nächsten Tag auch mitgeteilt:

„Federal Defendants further report, based on information from the Department of Homeland Security, that some gang members subject to removal under the Proclamation had already been removed from United States territory under the Proclamation before the issuance of this Court’s second order.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.19.0_5.pdf)

Mit „second order“ meinte die Regierung die schriftliche Anordnung von 7:26 PM EDT (und die Flüge starteten – grenz-nah – schon vor der mündlichen Anordnung, die circa eine 3/4 Stunde vor der schriftlichen erfolgte [siehe taz-Blogs vom 17.03.2025). Die mündliche Anordnung erwähnte die Regierung in der Mitteilung vom 16.03. gar nicht erst; und der Hinweis, „had already been removed from United States territory under the Proclamation before the issuance of this Court’s second order“, dürfte wohl dahingehend zu verstehen sein, daß sich die Regierung auch dann nicht an die Umkehr-Anordnung gebunden gefühlt hätte, wenn sie zwar schriftlich, aber zu einem Zeitpunkt, an dem die Flugzeuge den US-Luftraum bereits verlassen hatten, ergangen wäre.

Am Ende dürfte es also für das AEA-Verfahren auf die at least-Relativierung nicht ankommen.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d)

Sehen wir uns nun die zweite von der Regierung genannte Fundstelle an: Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d).

Dort heißt es in der Tat:

„(d) CONTENTS AND S COPE OF EVERY INJUNCTION AND RESTRAINING ORDER.

(1) Contents. Every order granting an injunction and every restraining order must:

(A) state the reasons why it issued;

(B) state its terms specifically; and

(C) describe in reasonable detail—and not by referring to the complaint or other document—the act or acts re-

strained or required.

(2) Persons Bound. The order binds only the following who receive actual notice of it by personal service or otherwise:

(A) the parties;

(B) the parties’ officers, agents, servants, employees, and attorneys; and

(C) other persons who are in active concert or participation with anyone described in Rule 65(d)(2)(A) or (B).“

(https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/civil-rules-procedure-dec2017_0.pdf, S. 86 der gedruckten und 106 der digitalen Seitenzählung)

Aber da steht nicht, daß es schriftlich erfolgen muß.

Die Entscheidung Lau v. Meddaugh

Damit kommen wir zur dritten von der Regierung genannten Fundstelle: Lau v. Meddaugh, 229 F.3d 624, 633 (2d Cir. 1976). Diese Entscheidung habe ich nicht gefunden, aber ich habe gefunden: Gilbert Lau v. Mark M. Meddaugh, 229 F.3d 121 (2d Cir. 2000). Auch (?) bzw.: Jedenfalls dort findet sich die Formulierung „contemplates the issuance of a written order“ tatsächlich:

„Finally, we note that the district court did not memorialize the oral order in a formal injunction. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d), which provides the standards for the form and scope of injunctions, contemplates the issuance of a written order. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 65(d). The provisions of this rule ‚are no mere technical requirements.‘ [Fußnote 2: A court’s failure to comply with the specific requirements of this rule does not render the injunction void. See. Clarkson Co. v. Shaheen, 544 F.2d 624, 632 (2d Cir.1976) (citations omitted).] Schmidt v. Lessard, 414 U.S. 473, 476, 94 S.Ct. 713, 38 L.Ed.2d 661 (1974). Compliance with this rule is essential because, ‚until a district court issues an injunction, or enters an order denying one, it is simply not possible to know with any certainty what the court has decided.‘ Gunn v. Univ. Comm. to End War in Viet Nam, 399 U.S. 383, 388, 90 S.Ct. 2013, 26 L.Ed.2d 684 (1970). Since an injunctive order prohibits conduct under threat of judicial punishment, fairness requires that the litigants receive explicit notice of precisely what conduct is outlawed. See Lessard, 414 U.S. at 476, 94 S.Ct. 713. Such notice and specificity foster effective enforcement. See id. Finally, detailed injunctions are needed to facilitate appellate review. See Fonar Corp. v. Deccaid Services, Inc., 983 F.2d 427, 429-430 (2d Cir.1993) (citing Lessard, 414 U.S. at 476-77, 94 S.Ct. 713). “[S]trict adherence to the Rules is better practice and may avoid serious problems in another case.” Clarkson, 544 F.2d at 633 (discussing Fed.R.Civ.P. 65(d) and 52(a)).“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/770711/gilbert-lau-v-mark-m-meddaugh/; Fußnote 2 aus der Entscheidung an entsprechende in den Haupttext eingefügt; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Nun mag in der Tat gesagt werden, daß Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d) damit rechnet (contemplates) oder davon ausgeht, daß es eine „written order“ gibt; aber Rule 67(d) schreibt es nicht vor.

Es mag in der Regel auch sinnvoll sein, Gerichtsentscheidungen schriftlich niederzulegen – insbesondere, wenn sie kompliziert sind (es z.B. um unterschiedliche Fristen für unterschiedliche Handlungen oder – unrunde – Geldbeträge u.ä. geht). Damit ist aber noch nicht gesagt, ob es neben dem schriftlichen Protokoll der mündlichen Verhandlung, in der die Entscheidung verkündet wird, auch noch einer zusätzlichen schriftlichen Niederlegung bedarf.

Dreingabe: Die Entscheidung Clarkson Co. v. Shaheen

Und vielleicht am wichtigsten: Der 2. Appeals Court zitiert in der Entscheidung Lau v. Meddaugh in Fußnote 2 ausdrücklich seine eigene ältere Entscheidung Clarkson Co. v. Shaheen, mit der Aussage, daß selbst eine Mißachtung Regel 65d, die Entscheidung nicht ungültig macht (does not render the injunction void), ohne diese Formulierung zu revidieren. Dort heißt es mit Kontext um die in der neueren Entscheidung zitierten Formulierung herum:

„No point on appeal is made of the lack of a formal injunction order in this case. We note that a court’s failure to comply with the specific requirements of Fed.R.Civ.P. 65(d) as to the form of an injunction does not render the order void. 11 C. Wright & A. Miller, supra, § 2955, at *633538; cf. Bethlehem Mines Corp. v. United Mine Workers, 476 F.2d 860, 862 (3d Cir. 1973) (failure to comply with formal requisites for preliminary injunction does not deprive court of jurisdiction or of power to hold violators in contempt). We would point out, however, that Rule 65(d), read together with Rule 52(a), requires that adequate findings of fact and conclusions of law be set forth, and specifically requires that the operative passages of the order granting an injunction or restraining order be set out in detail, thus enabling the order to be obeyed easily and enforced effectively. See Schmidt v. Lessard, 414 U.S. 473, 476, 94 S.Ct. 713, 38 L.Ed.2d 661 (1974) (per curiam); 11 C. Wright & A. Miller, supra, § 2955. While no difficulty has arisen in this case, we strenuously caution that strict adherence to the Rules is better practice and may avoid serious problems in another case.“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/8912237/clarkson-co-v-shaheen/#632)

Die Entscheidung Garcia v. Yonkers Sch. Dist.

Sehen wir uns nun die vierte von der Trump-Regierung genannte Fundstelle an: Garcia v. Yonkers Sch. Dist., 561 F.3d 97, 105 (2d Cir. 2009). Auch dort heißt es nur:

„Thus, no specific findings of facts were made to support the District Court’s ‚grant‘ of the preliminary injunction as is required. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 65(d)(1); see also Fed.R.Civ.P. 52(a)(2) (stating that a court must ’state the findings and conclusions that support its action‘ when granting or refusing an interlocutory injunction). Requirements for the form and content of preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders are properly met by a written order, a document lacking here. See, e.g., Lau v. Meddaugh, 229 F.3d 121, 123 (2d Cir.2000) (‚Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d), which provides the standards for the form and scope of injunctions, contemplates the issuance of a written order.‘); Bates v. Johnson, 901 F.2d 1424, 1427 (7th Cir.1990) (‚Oral statements are not injunctions.‘).“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/1373478/garcia-v-yonkers-school-district/)

Der Satz mit „properly“ hört sich für mich so an, daß

-

die wirklichen „[r]equirements for the form and content of preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders“ das sind, was in Rule 65 tatsächlich drin steht („state the reasons why it issued“ usw.);

-

und die Schriftform ist ein bloßes Mittel, das geeignet ist, diese requirements besonders gut zu erfüllen, aber selbst nicht vorgeschrieben ist.

Außerdem weisen die Kläger und Antragsteller in ihrer Antwort von Montag (auf den Regierungs-Schriftsatz vom 25.03.) darauf hin, daß es etwas weiter oben in der Entscheidung Garcia v. Yonkers Sch. Dist. auch noch heißt:

„In this case, the District Court’s statements at the hearing do not describe in reasonable detail the extent of the acts restrained, such as whether the School District would be restrained from imposing a lesser punishment.“

Das Mündliche wird also durchaus nicht für generell irrelevant gehalten, sondern im dortigen Fall nur nicht für ausreichend.

Plaintiffs (Kläger/Antragsteller) sagen (daher):

„The other two cases [Die Entscheidung Garcia v. Yonkers Sch. Dist. sowie Adkins v. Nestle Purina PetCare] support Plaintiffs’ position. They show courts of appeals looking to oral statements delivered from the bench as authoritative guidance regarding the contours of a district court’s written injunction.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.70.0.pdf)

Soviel zur Entscheidung Garcia v. Yonkers Sch. Dist.

Fundstellen, die die Kläger und Antragsteller anführen

Kommen wir nun zu einigen Fundstellen, die die Kläger und Antragsteller im ersten Absatz des hier relevanten Abschnittes ihres Schriftsatzes von Montag anführen:

„A court’s unambiguous oral order is binding. See In re LaFande, 919 F.3d 554, 562 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (judge’s ‚in-person order‘ sufficient to compel a litigant on penalty of contempt); see also In re U.S. Bureau of Prisons, 918 F.3d 431, 437 n.3 (5th Cir. 2019) (citing Lau v. Meddaugh, 229 F.3d 121, 123 & n.2 (2d Cir. 2000)); In re Charlotte Observer, 921 F.2d 47, 48, 50 (4th Cir. 1990)). And counsel for Defendants stated that he ‚understood‘ on March 15 that the Court had orally directed the government to turn planes around immediately. Mar. 21 Tr. 5–6 (“Your Honor, I understood your intent, that you meant that to be effective at that time.”); see United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 682 F. Supp. 3d 32, 49 (D.D.C. 2023) (declining to construe injunction in favor of the enjoined party where meaning was unambiguous from trial record).“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.70.0_1.pdf, S. 2; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Die Entscheidung in In re LaFande

In der Entscheidung In re LaFande, 919 F.3d 554, die von dem Appeals Court („D.C. Cir.“), der dem Discourt Court für den District of Columbia übergeordnet ist, stammt, geht es um ein standesrechtliches Verfahren gegen einen Rechtsanwalt. Der Tenor der Entscheidung lautet: „We agree that LeFande committed the alleged rules violations and agree with those Board members who recommend that he be disbarred.“

Ich bin aber weder in der Lage, die Formulierung „in-person order“ und – wegen abweichender Paginierung – noch überhaupt die gemeinte Stelle zu finden. Auch die Wörter „oral“ und „written“ kommen in der Entscheidung nicht vor. (Vielleicht ist es nötig, die vorausgegangenen Entscheidung zu kennen, um zu wissen, daß es dort um eine mündliche Entscheidung ging, die mißachtet wurde.)

Die Entscheidung In Re U.S. Bureau of Prisons, DEPT. OF JUSTICE

Kommen wir dann zur zweiten von den Klägern und Antragsteller genannten Stelle:

„Other circuits similarly treat oral injunctions as enforceable orders. See, e.g., Lau v. Meddaugh, 229 F.3d 121, 123, 123 n.2 (2d Cir. 2000); In re Charlotte Observer, 921 F.2d 47, 48, 50 (4th Cir. 1990). We agree with the Second Circuit that, although Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d) ‚contemplates the issuance of a written order,‘ a district ‚court’s failure to comply with the specific requirements of this rule does not render the injunction void.‘ Lau, 229 F.3d at 123, 123 n.2; see also Test Masters Educ. Servs., Inc. v. Singh, 428 F.3d 559, 577 (5th Cir. 2005) (explaining that a district court’s failure to fully comply with Rule 65(d) ‚does not require that the injunction be reversed or vacated‘) (quotation omitted).“

(https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/4599962/in-re-us-bureau-of-prisons-dept-of-justice/; Hv. + Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Diese Entscheidung stammt vom 5. Appeal Court – also wiederum einem, der nicht dem dem Discourt Court für den District of Columbia übergeordnet ist, und er macht die Formulierungen in der oben schon zitierten Lau-Entscheidung stark, die die Trump-Regierung in ihrem Schriftsatz überging.

Die Entscheidung In re Charlotte Observer

Die Entscheidung In re Charlotte Observer, 921 F.2d 47 endet mit folgendem Satz:

„the oral injunctions issued by the district court on October 31, 1990, forbidding the reporters of The Charlotte Observer and the Rock Hill Herald to disclose the name of the attorney mentioned in open court are hereby vacated.“

Die mündlichen Entscheidungen des District Court wurden also als wirksam, aber inhaltlich fehlerhaft angesehen – und wegen letzterem aufgehoben. (Wären sie gar nicht erst wirksam gewesen, hätten sie weder aufgehoben werden können noch müssen.)

(Das Protokoll vor der mündlichen Verhandlung vom 21. März [Mar. 21 Tr. 5–6] ist noch nicht öffentlich verfügbar; aber vgl. Kyle Cheney [Politico]: „DOJ lawyer Drew Ensign says he believed Boasberg intended the planes to be turned around when he issued his oral order in court over the wekend: ‚I understood the intent that you meant that to be effective at that time.'“

Und die Entscheidung United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 682 F. Supp. 3d 32 konnte ich online nicht finden.)

Resumee

1. Es gibt anscheinend keine Norm im US-Recht, die ausdrücklich regelt, ob gerichtliche Anordnungen – insbesondere der hier in Rede stehenden Art (Temporary Restrainung Order) – schriftlich erfolgen müssen oder auch mündlich ergehen dürfen.

2. Es gibt aber Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d), die u.a. bestimmt, „Every order granting an injunction and every restraining order must: (A) state the reasons why it issue [… usw.]“.

3. Dort ist aber kein Schriftform-Erfordernis aufgestellt.

4. Allerdings ist der Trump-Regierung zuzugeben, daß sich den tatsächlich genannten Erfordernissen besser genüge tun läßt, wenn die Anordnung schriftlich ergeht.

5. Auch BürgerInnen dürften, wenn eine gerichtliche Anordnung nicht gegen die Regierung, sondern gegen sie selbst ergeht, ein Interesse habe, die Anordnung schriftlich zu erhalten.

6. Die Rechtsprechung zur Frage, ob gerichtliche Anordnungen – insbesondere der hier in Rede stehenden Art (Temporary Restrainung Order) – schriftlich erfolgen müssen oder auch mündlich ergehen dürfen, scheint uneinheitlich zu sein.

7. a) Nach dem Schriftsatz der Kläger und Antragsteller in dem AEA-/TdA-Verfahren von Montag zu urteilen, wird in der Rechtsprechung der Appeals Court besonders kritisch gesehen, wenn gar keine schriftliche Anordnung ergeht, während es durchaus üblich zu sein scheint, schriftliche Anordnung im Lichte mündlicher Äußerungen des Gerichts auszulegen: „All but two of Defendants’ cases are inapposite. […]. They address situations where the district court failed to issue a written order entirely„ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.70.0_1.pdf, S. 4; Hv. hinzugefügt)

b) Die Trump-Regierung scheint in dem AEA-/TdA-Verfahren dagegen davon auszugehen, es bestehe ein striktes Schriftform-Erfordernis: „It is well-settled that an oral directive is not enforceable as an injunction. See Bates v. Johnson, 901 F.2d 1424, 1427 (7th Cir. 1990) (‚Oral statements are not injunctions.‘)“ – aber das ist genau ein Fall, wo die mündlichen Anordnungen gar nicht verschriftlicht wurden: „Like the state, we are puzzled by the district judge’s unwillingness to put on paper what he said several times in court.“