.

Entscheidung des zuständigen Spruchkörpers

Der 5. US-Appeals Court reagiert auf die Supreme Court-Entscheidung (Tren de Aragua III) von Freitag. Der dreiköpfige Spruchkörper, dessen Entscheidung von Ostersamstag vom Supreme Court aufgehoben, reagierte sachlich angemessen:

„Last Friday, the Supreme Court vacated the judgment of our court, which had dismissed this appeal for lack of jurisdiction. The Court remanded the case back to us for further proceedings, and directed us to proceed ‚expeditiously.‘ A.A.R.P. v. Trump, 605 U.S. _, _ (2025).

Accordingly, this matter is expedited to the next available randomly designated regular oral argument panel.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134.25.1.pdf, S. 2)

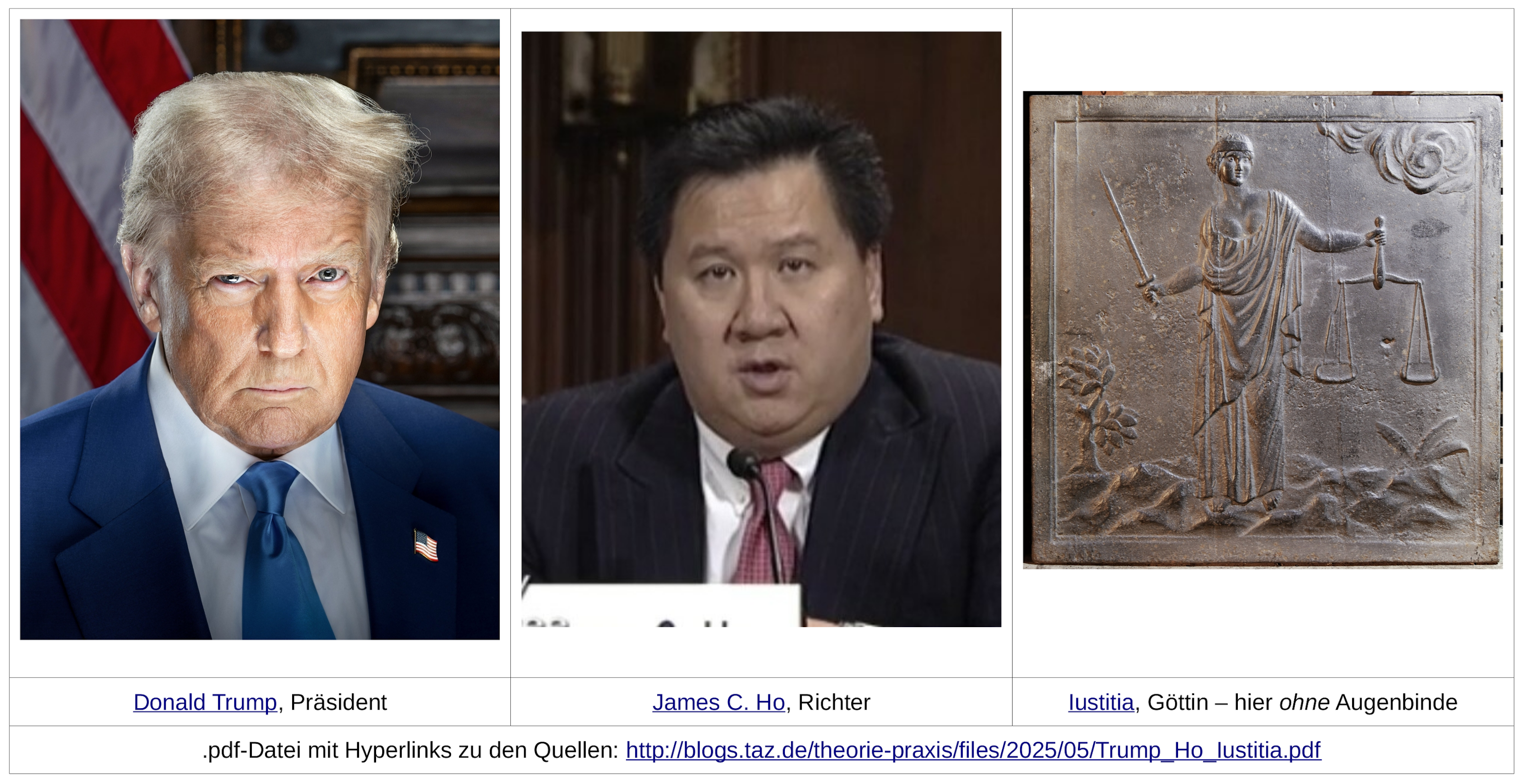

concurring vote von Richter James C. Ho

Der – wie Richterin Wilson von Trump nominierte – Richter Ho (das dritte Spruchkörper-Mitglied ist die von Biden nominierte Richterin Ramirez) gab ein concurring vote ab, das aber nichts zur Begründung der jetzt getroffenen Entscheidung beiträgt.

Er beharrt nicht nur auf seiner Auffassung, daß „Petitioners … should not be allowed to proceed in this appeal“ (was ihm freisteht, aber für die Entscheidung, die jetzt zu treffen war, irrelevant ist), sondern bezeichnet außerdem die Antragsteller als „identified as members of Tren de Aragua, a designated foreign terrorist organization“ (beides S. 3), obwohl bisher kein Gericht Feststellungen dazu getroffenen hat, und die Antragsteller eine Mitgliedschaft bestreiten:

„Petitioner A.A.R.P. is a Venezuelan national who is detained at Bluebonnet Detention Center in Anson, Texas. A.A.R.P. fled Venezuela because he and his family were persecuted there in the past for their political beliefs and for publicly protesting against the current Venezuelan government. […] he denies any connection with TdA.“

„W.M.M. is a Venezuelan national who is also detained at Bluebonnet Detention Center in Anson, Texas. W.M.M. fled Venezuela after the Venezuelan military harassed and assaulted him because they believed that he did not support the Maduro regime. […]. W.M.M. denies having any connection with TdA.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.1.0.pdf, S. 4, 5 der gedruckten bzw. 5, 6 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt)

Außerdem wirft er dem Supreme Court Respeklosigkeit gegenüber dem Präsidenten und dem erstinstanzlich zuständigen gewesenen District Court vor:

„I write to state my sincere concerns about how the district judge as well as the President and other officials have been treated in this case. I worry that the disrespect they have been shown will not inspire continued respect for the judiciary, without which we cannot long function.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134.25.1.pdf, S. 3)

Begründung für den Vorwuf:

„Judges do not roam the countryside looking for opportunities to chastise government officials for their mistakes. Rather, our job is simply to decide those legal disputes over which Congress has given us jurisdiction. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1), appellate courts have jurisdiction to review interlocutory orders of the district courts that ‚refus[e]‘ to enter an injunction. That includes orders that have ‚the practical effect of refusing an injunction.‘ Carson v. Am. Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 79, 84 (1981).“

(ebd., S. 3 f.)

Selektive Tatsachenwahrnehmung …

Letzteres sei aber an Gründonnerstag und Karfreitag nicht der Fall gewesen:

„The court simply advised Petitioners that the Government would get 24 hours to respond before it would issue a ruling, one way or another.[…]. So when they sought emergency relief at 12:34 a.m. on April 18, Petitioners ‚were fully aware that the District Court intended to give the Government 24 hours to file a response.‘ A.A.R.P., 605 U.S. at _ (Alito, J., dissenting). They ’said nothing about a plan to appeal if the District Court elected to wait for that response.‘ Id. At 12:48 p.m. on April 18, however, Petitioners ’suddenly informed the court that they would file an appeal if the District Court did not act within 42 minutes, i.e., by 1:30 p.m.‘ Id.„

(ebd., S. 4; zu den „24 hours“ siehe:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.41.0.pdf, S. 2 unten und https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69898198/wmm-v-donald-j-trump/?filed_after=&filed_before=&entry_gte=&entry_lte=&order_by=desc#entry-29 [17.04.2025])

Dies läßt aber außer Acht, daß die Antragsteller in ihrem Antrag von Karfreitag, den 18.4.um 12:34 a.m. (0:34 Uhr) vorgetragen hatten:

„Petitioners have learned that officers at Bluebonnet have distributed notices under the Alien Enemies Act, in English only, that designate Venezuelan men for removal under the AEA, and have told the men that the removals are imminent and will happen tonight or tomorrow. See Exh. A (Brown Decl.). These removals could therefore occur before this matter may be heard and before the government’s response within 24 hours. See Order, ECF No. 29 (providing that if any emergency motion is filed, the opposing party shall have 24 hours to file a response).“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.30.0.pdf, S. 1; Hyperlinks + Hv. hinzugefügt)„Counsel for Petitioners contacted counsel for the government by email [von Gründonnerstag] at 4:49pm CT, even before hearing about the distribution of notices at Bluebonnet, to ask if the government would make the same representations as to the putative class members as it did for the two named Petitioners. Counsel for the government did not respond to that correspondence. After then hearing that notices were being distributed at the Bluebonnet facility, we again contacted the government, at 6:23 pm CT, to ask whether it was accurate that the government had begun distributing AEA notices to Venezuelan men at the facility. At 6:36pm CT, counsel for the government said they would inquire and circle back. At 8:11pm CT, the government responded that the two named Petitioners had not been given notices. We immediately responded that we were inquiring about putative class members. At 8:41pm CT, the government wrote: ‚We are not in a position at this time to share information about unknown detainees who are not currently parties to the pending litigation.‘„

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.30.0.pdf, S. 1 f., FN 1; Hv. hinzugefügt)

… und ein schiefer Vergleich

Auf S. 5 setzt Richter Ho dann wie folgt fort:

„Notably, the Justices themselves have expressed concerns about making decisions under far more forgiving time constraints than those demanded here. Recall the emergency relief sought in Does 1-3 v. Mills, 142S. Ct. 17 (2021). Members of the Court expressed concern about the ‚use [of] the emergency docket to force the Court‘ to ‚grant … extraordinary relief‘ ‚on a short fuse without benefit of full briefing.‘ Id. at 18 (Barrett, J., concurring in the denial of application for injunctive relief).

The amount of time considered too short in Does 1-3 was nine days. Compared to 42 minutes, however, nine days is a lifetime to decide a motion. So the district court reasonably assumed that the principle invoked in Does 1-3 to justify denying relief to law-abiding citizens concerned about their religious liberties in the COVID-19 era would likewise justify denying relief to illegal alien members of a foreign terrorist organization.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134.25.1.pdf, S. 5; Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

Richter Ho wiederholt dort also den gar nicht (zumal nicht im Rahmen eines adversatorischen [vgl. lat. adversārius] Verfahrens) untersuchten Vorwurf, es handele sich bei den Antragstellern um „members of a foreign terrorist organization“ – noch dazu um solche, die illegal in die USA eingewandtert seien („illegal alien“)… (vgl. dazu, wenn auch nicht bezogen auf die nordtexanischen Antragsteller, sondern auf die am 15. März Abgeschobenen folgende Analyse eines im US-Sinne „libertären“ – also nicht anarchistischen, sondern extrem neoliberalen -, aber migrationsfreundlichen Instituts: https://www.cato.org/blog/50-venezuelans-imprisoned-el-salvador-came-us-legally-never-violated-immigration-law [„dozens of these men never violated immigration laws“ <*>]).

Und der Vergleich zwischen

-

Beschwerlichkeiten (Beten muß nicht unbedingt im Kollektiv stattfinden) bei der Ausübung religiöser Freiheiten während einer tatsächlich stattfindenen Pandemie

-

einer unmittelbar drohenden Abschiebung von bloßen vermeintlichen Mitgliedern eines bloß vermeintlich terroristischen Personenzusammenhangs, dessen Organisations-Charakter strittig ist, in einen Folterknast ohne vorherige Gewährung von rechtlichem Gehör

und

hingt auch etwas.

Auf S. 6 findet sich dann der Sache nach eine weitere Wiederholung:

„Rather than commend the district court, however, the Supreme Court charged the district court with ‚inaction—not for 42 minutes but for 14 hours and 28 minutes.‘ Id. at _. This inaction was, according to the Court, tantamount to ‚refusing‘ to rule on the injunction. Id. at _.

This charge is worth exploring. To get to 14 hours and 28 minutes (rather than 42 minutes), the Court was obviously starting the clock at 12:34 a.m., rather than 12:48 p.m. (when Petitioners told the district court for the first time that they wanted a ruling before the Government could respond).

But starting the clock at 12:34 a.m. not only ignores the court’s express instructions respecting the Government’s right to respond. It also ignores the fact that the Court is starting the clock at — 12:34 a.m.

We seem to have forgotten that this is a district court — not a Denny’s.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134.25.1.pdf, S. 6; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Dies ignoriert wiederum, daß die Antragsteller dargelegt hatten: „These removals could therefore occur before this matter may be heard and before the government’s response within 24 hours.“ (s.o.)

Damit hätte sich der District Court zumindest rechtzeitig auseinandersetzen müssen, wenn er denn dem Antrag der Antragsteller nicht folgen mag.

Nicht nach Ansicht von Richter Ho – dieser schreibt sodann schreibt:

„This is the first time I’ve ever heard anyone suggest that district judges have a duty to check their dockets at all hours of the night, just in case a party decides to file a motion.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134.25.1.pdf, S. 6)

Es ist ja aber gar nicht so, daß der District Court-Richter den Antrag nicht bemerkt hätte; sondern er wollte erklärtermaßen trotzdem die 24 Stunden-Antwort-Frist abwarten<**>. Außerdem wurde er schon deutlich vor Mitternacht (nämlich gegen 19:35 Uhr Ortszeit) telefonisch auf die Dringlichkeit der Angelegenheit hingewiesen:

„We understand that our clients at the Bluebonnet Detention Center are being given orders to sign, Alien Enemy orders, and told they may be removed as soon as tonight or first thing in the morning. This is related to the Alien Enemies Act.

We would like to talk to the Judge immediately or — and have the Judge issue an order to have them not removed. The Judge’s understanding today in his opinion was that the government’s representations would keep the proposed class safe. It appears that they are being asked to–to be–to sign papers for their immediate removal.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.47.1.pdf, S. 2; vgl. dazu:

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69898198/wmm-v-donald-j-trump/?filed_after=&filed_before=&entry_gte=&entry_lte=&order_by=desc#entry-29 [kurze Noitz]

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.47.0.pdf [4 Seiten]; https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.65.0.pdf [3 Seiten]; https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.65.1_1.pdf [3 Seiten: mail-Wechsel zwischen Betroffenen-Anwälten und Regierung])

Richter Ho setzt trotz alledem noch eins drauf:

„If this is going to become the norm, then we should say so: District judges are hereby expected to be available 24 hours a day — and the Judicial Conference of the United States and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts should secure from Congress the resources and staffing necessary to ensure 24-hour operations in every district court across the country.

If this is not to become the norm, then we should admit that this is special treatment being afforded to certain favored litigants like members of Tren de Aragua — and we should stop pretending that Lady Justice is

blindfolded.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134/gov.uscourts.ca5.224134.25.1.pdf, S. 6)

Auf S. 8 ‚entdeckt‘ Richter Ho dann doch das „adversarial legal system“ der USA – um zu begründen, warum es seines Erachtens richtig gewesen wäre, der Regierung Gelegenheit zu geben, die Antragsteller oder jedenfalls die anderen Angehörigen der beantragten „Klasse“ ohne rechtliches Gehör abzuschieben (diese Gelegenheit zu verschaffen, wäre der praktische Effekt davon gewesen, der Regierung die 24 Stunden Gehörs-Frist zu gewähren)!

„Our adversarial legal system has long been premised on the notion that judges should impartially consider the views of both sides of any dispute before issuing a ruling. See 605 U.S. at _ (Alito, J., dissenting) (‚the court took the entirely reasonable position that it would wait for the Government to respond to the applicants’ request for a temporary restraining order (TRO) before acting‘); see also Lefebure v. D’Aquilla, 15 F.4th 670, 674–75 (5th Cir. 2021).“

(ebd., S. 8)

Der District Court-Richter hätte, wenn er nicht sogleich dem TRO-Antrag stattgeben wollte, zumindest einen administrative stay (‚Eil-Eil-Eil-Rechtsschutz‘) gegen die Abschiebungen verfügen können, bis er über den TRO-Antrag entscheidet. Dies wäre für die Regierung bloß eine kurze zeitliche Verzögerung gewesen; für die Antragsteller oder jedenfalls die anderen Angehörigen der beantragten „Klasse“ stand dagegen auf dem Spiel, an einen Ort abgeschoben zu werden, von dem die Regierung behauptet, daß er sich jenseits ihrer Möglichkeiten befinde, fälschlicherweise abgeschobene Leute zurückzuholten (vgl. den Fall Abrego Garcia und die letzten Entwicklungen in dem ursprünglichen Washingtoner Verfahren vor Richter Boasberg <***>).

Das Votum von Ho endet dann mehr oder minder mit dem Satz:

„Our current President deserves the same respect [nämlich die Gelegenheit zu bekommen, „to express <… his> views in any pending case to which they are a party, before issuing any ruling“].“

(ebd., S. 8)

Richter Ho im Glashaus

Again: Die Entscheidungen des Supreme Court von Ostsamstag und vergangenem Freitag dienten gerade dazu, nicht nur der Regierung, sondern auch den Antragstellern rechtliches Gehör zu verschaffen – audiatur et altera pars -, bevor vollendete Tatsachen geschaffen werden:

„I understand and agree with the Court’s decision to grant a temporary injunction. The injunction simply ensures that the Judiciary can decide whether these Venezuelan detainees may be lawfully removed under the Alien Enemies Act before they are in fact removed.“

(https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a1007_g2bh.pdf, S. 9 der Datei, Kavanaugh, concurring; Hv. i.O.)

Der District Court Nordtexas hatte Gründonnerstagnachmittag in seiner damaligen Entscheidung argumentiert:

„the Supreme Court has already made clear that the alleged immediate removals prior to notice and the opportunity for judicial review, which form the basis of the petitioners’ motion, are illegal. See id. And the government recognized this reality in the Supreme Court. Id. […]. the Court has no basis upon which to believe that the government is going to defy the Supreme Court’s clear directives in J.G.G. or the government’s own representations to the Supreme Court and to this Court. Thus, in light of J.G.G. and the government’s representations in its response (Dkt. No. 19), the petitioners’ conjecture is too

speculative to support the exceptional remedy requested.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.27.0_3.pdf, S. 6 f., 8)

Daran anknüpfend schrieben die Antragsteller in ihrem mitternächtlichen (von Grünmdonnerstag zu Karfreitag) Antrag:

„Petitioners-Plaintiffs (“Petitioners”) and the proposed class seek emergency relief in light of developing and alarming circumstances: since the Court’s order denying a TRO this afternoon, Petitioners have learned that officers at Bluebonnet have distributed notices under the Alien Enemies Act, in English only, that designate Venezuelan men for removal under the AEA, and have told the men that the removals are imminent and will happen tonight or tomorrow. […].

As detailed in the Brown Declaration, in the hours after this Court’s order on the TRO, Attorney Brown’s client, F.G.M., was approached by ICE officers, accused of being a member of Tren de Aragua, and told to sign papers in English. […]. In addition to Brown’s client, immigration lawyers and family members of people detained at Bluebonnet are reporting that the forms are being passed out widely to the dozens of Venezuelan men who have been brought there over the past few days. Exh. B (Brane Declaration); see also Exh. C (Collins Decl.); Exh. D (Siegel Decl.).“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.30.0.pdf, S. 1, 2; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Wer hat sich nun in diesem Verfahren am Grundsatz eines adversatorischen Verfahrens vergangen – der Supreme Court? Oder die Regierung mit Beihilfe von District und Appeals Court? Und wie will es Richter Ho mit dem Grundsatz eines adversatorischen Verfahrens vereinbaren, daß er die Antragsteller der Mitgliedschaft in einer vermeintlichen terroristischen Organisation bezichtigt, ohne ihnen rechtliches Gehör gewährt zu haben?

<*>

„Shortly after the US government illegally and unconstitutionally transported about 240 Venezuelans to be imprisoned in El Salvador’s horrific ‚terrorism‘ prison on March 15, CBS News published their names. A subsequent CBS News investigation found that 75 percent of the men on that list had no criminal record in the United States or abroad. Less attention has been paid to the fact that dozens of these men never violated immigration laws either.“ (Hv. hinzugefügt)

<**>

„The Court took the motion under advisement and was actively working on the motion. Pursuant to the Court’s previous order (Dkt. No. 29), the government has until 12:34 a.m. CT on April 19, 2025, to respond. A.A.R.P. and W.M.M. asserted in their second emergency motion for a temporary restraining order (Dkt. No. 30) and their motion for an emergency status conference (Dkt. No. 34) that the 24-hour response period was too long because the respondents are going to remove from the United States members of the putative class. The Court did not order the government to file an earlier motion because it believed that 24 hours was an appropriate time for the government to respond and in light of the government’s prior representations.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915/gov.uscourts.txnd.402915.41.0.pdf, S. 3; Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

<***>

„Abrego Garcia is been held in the sovereign, domestic custody of the independent nation El Salvador. DHS [Department of Homeland Security] does not have authority to focibily extract an alien form the domestic custody a foreign sovereign nation.“ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.578815/gov.uscourts.mdd.578815.77.0.pdf, S. 2, Nr. 7)

In Bezug auf die am 15. März nach El Salvador abgeschobenen, vermeintlichen TdA-Mitglied: „regain custody over foreign terrorists“ / „regaining custody of foreign terrorists“ / „regaining custody of members of Tren de Aragua“ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cadc.41957/gov.uscourts.cadc.41957.01208733712.0_2.pdf, S. 1, 3, 4 der gedruckten bzw. S. 2, 4, 5 der digitalen Seitenzählung), was die Behauptung impliziert, die Leute seien im Moment nicht in US-, sondern salvadorianischer custody.

„The evidence produced by Respondents established that the United States does not have custody over the CECOT class.“ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.126.0.pdf, S. 1) / “ the members of TdA in CECOT are being detained under the authority of El Salvador, a sovereign nation“ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436/gov.uscourts.dcd.278436.108.0_1.pdf, S. 4 der gedruckten bzw. 7 der digitalen Seitenzählung)