Am 06.02.2025 hatte ein in den 80er Jahren vom damaligen Präsidenten Reagan nominierter Richter entschieden, Trumps Staatsangehörigkeits-Verordnung bis auf weiteres auszusetzen. Die Trump-Regierung wandte sich umgehend an die zweite Instanz und beantragte ihrerseits, die Entscheidung des Erstrichters teilweise auszusetzen.

„For the foregoing reasons, this Court should stay the district court’s nationwide preliminary injunction except as to the Individual Plaintiffs. At a minimum, this Court should grant a stay as to all nonparties.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303.21.0_2.pdf, S. 24 der gedruckten bzw. S. 26 der digitalen Seitenzählung)

Im Verfahren gibt es zwei AntragstellerInnen-/KlägerInnen-Gruppen: Die im vorstehenden Zitat erwähnten „Individual Plaintiffs“ (Schwangere mit unsicherem Aufenthaltsstatus) und die vier US-Bundesstaaten Washington, Orgeon, Arizona und Illinois. Das Gericht erster Instanz hatte Trumps Executive Order zum Staatsangehörigkeitsrecht USA-weit außer Vollzug gesetzt.

Der 9th Appeal Court hat nun die teilweise Aussetzung der Entscheidung des Erstrichters mit zwei unterschiedlichen Begründungen abgelehnt:

Zwei Richter (Canby [1980 von Jimmy Carter nominiert] und M[ilan Dale] Smith [2006 von Georg W. Bush nominiert]) verneinten – ohne nähere Begründung – die Erfolgsaussichten der Trump-Regierung in der Hauptsache:

„Appellants have not made a ’strong showing that [they are] likely to succeed on the merits‘ of this appeal.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303.37.0.pdf, S. 1)

Danielle Jo Forrest (2019 von Trump nominiert) enthielt sich dagegen einer Prognose für die Hauptsache und argumentierte vielmehr folgendermaßen:

„The Government has presented its motion for a stay pending appeal on an emergency basis, asserting that it needs the relief it seeks by February 20. Thus, the first question that we must ask in resolving this motion is whether there is an emergency that requires an immediate answer. Granting relief on an emergency basis is the exception, not the rule. […]. Ninth Circuit Rule 27-3 [https://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/uploads/rules/frap.pdf, S. 96 f.], which governs emergency motions, provides that ‚[i]f a movant needs relief within 21 days to avoid irreparable harm, the movant must,‘ among other things, ’state the facts showing the existence and nature of the claimed emergency.‘ If the movant fails to demonstrate that irreparable harm will occur immediately, emergency relief is not warranted, and there is no reason to address the merits of the movant’s request. Here, the Government has not shown that it is entitled to immediate relief.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303.37.0.pdf, S. 2, 3)

Zu Begründung führt sie aus:

„Its [der Regierung] sole basis for seeking emergency action from this court is that ‚[t]he district court has … stymied the implementation of an Executive Branch policy … nationwide for almost three weeks.‘ That alone is insufficient. It is routine for both executive and legislative policies to be challenged in court, particularly where a new policy is a significant shift from prior understanding and practice. E.g., West Virginia v. EPA, 597 U.S. 697 (2022); Dep’t of Homeland Sec. v. Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 591 U.S. 1 (2020); Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius [recte: Sebilius], 567 U.S. 519 (2012). And just because a district court grants preliminary relief halting a policy advanced by one of the political branches does not in and of itself an emergency make. A controversy, yes. Even an important controversy, yes. An emergency, not necessarily.“

(ebd., S. 3; Hyperlinks und Hv. hinzugefügt)

Ein bißchen sagt allerdings auch Forrest zur Hauptsache – nämlich dazu, wie sie bisher gehandhabt wurde, und daß dies dagegen spreche, daß jetzt ein „irreparable harm“ drohe, wenn die Trump-Regierung nicht sofort anders verfahren dürfe, als bisher verfahren wurde:

„To constitute an emergency under our Rules, the Government must show that its inability to implement the specific policy at issue creates a serious risk of irreparable harm within 21 days. The Government has not made that showing here. Nor do the circumstances themselves demonstrate an obvious emergency where it appears that the exception to birthright citizenship urged by the Government has never been recognized by the judiciary, see United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, 693 (1898), and where executive-branch interpretations before the challenged executive order was issued were contrary, see, e.g., Walter Dellinger, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, Legislation Denying Citizenship at Birth to Certain Children Born in the United States, 19 O.L.C. 340, 340–47 (1995).“

(ebd., S. 3 unten / 4 oben; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

Dann sagt sie aber noch, daß dieser Hinweis nicht als Prognose für die Hauptsache zu verstehen sei:

„To be clear, I am saying nothing about the merits of the executive order or how to properly interpret the Fourteenth Amendment. I merely conclude that, whatever the merits of the parties’ respective positions on the issues presented, the Government has not shown it is entitled to immediate relief from a motions panel before assignment of the case to a merits panel.“

(ebd., 4 Mitte)

Forrest führt sodann – „[a]side from the legal standard governing emergency relief“ – noch „three prudential reasons“ an, die ihres Erachtens „support not addressing the merits of the Government’s motion for a stay at this point“ (ebd., 4 unten / 5 oben), von denen hier zunächst nur der dritte Grund und der daran abschließend vorletzte Absatz der Begründung von Forrest zitiert sei:

„Third, and relatedly [zum zweiten Grund], quick decision-making risks eroding public confidence. Judges are charged to reach their decisions apart from ideology or political preference. When we decide issues of significant public importance and political controversy hours after we finish reading the final brief, we should not be surprised if the public questions whether we are politicians in disguise. In recent times, nearly all judges and lawyers have attended seminar after seminar discussing ways to increase public trust in the legal system. Moving beyond wringing our hands and wishing things were different, one concrete thing we can do is decline to decide (or pre-decide) cases on an emergency basis when there is no emergency warranting a deviation from our normal deliberate practice.

I do not mean to suggest that emergency relief is never warranted. There are cases where quick action is necessary. But they are rare. There must be a showing that emergency relief is truly necessary to prevent immediate irreparable harm. The Government did not make that showing here, and, therefore, there is no reason for us to say anything about whether the factors governing the grant of a stay pending appeal are satisfied. The Government may seek the relief it wants from the merits panel who will be assigned to preside over this case to final disposition.“

(ebd., S. 6 unten bis 7 Mitte)

Nun noch der zweite Grund von Forrest, von dem sie sagt, daß der dritte Grund mit ihm zusammenhänge:

„Second, as a motions panel, we are not well-suited to give full and considered attention to merits issues. Take this case. The Government filed its emergency motion for a stay on February 12, requesting a decision by February 20 — just over a week later. We ordered a responsive brief from the Plaintiff States by February 18, and an optional reply brief from the Government by February 19—one day before the Government asserts it needs relief. This is not the way reviewing courts normally work. We usually take more time and for good reason: our duty is to ‚act responsibly,‘ not dole out ‚justice on the fly.‘ East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, 933 F.3d at 661 (citation omitted). We must make decisions based on reasoned judgment, not gut reaction. And this requires understanding the facts, the arguments, and the law, and how they fit together. See TikTok Inc. v. Garland, 604 U.S. —, 145 S. Ct. 57, 63 (2025) (observing that courts should be particularly cautious in cases heard on an expedited basis); id. at 75 (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (‚Given just a handful of days after oral argument to issue an opinion, I cannot profess the kind of certainty I would like to have about the arguments and record before us.‘ [https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24-656diff_d1of.pdf, S. 24 der Datei]). Deciding important substantive issues on one week’s notice turns our usual decision-making process on its head. We should not undertake this task unless the circumstances dictate that we must. They do not here.

(ebd., S. 5 unten / 6 oben; Hyperlink und eckige Klammer hinzugefügt)

Mir scheint die Argumentation von Forrest die im gegenwärtigen Verfahrensstadium angemessenere Begründung zu sein – und auch die, die in Bezug auf das aktuelle politische Umfeld das wichtigere Signal setzt – die Regierung steht nicht außerhalb der gerichtlichen Kontrolle: „It is routine for both executive and legislative policies to be challenged in court, particularly where a new policy is a significant shift from prior understanding and practice. […]. And just because a district court grants preliminary relief halting a policy advanced by one of the political branches does not in and of itself an emergency make. A controversy, yes. Even an important controversy, yes. An emergency, not necessarily. […] our duty is to ‚act responsibly,‘ not dole out ‚justice on the fly.‘ […]. We must make decisions based on reasoned judgment, not gut reaction.“ (siehe oben)

Die Mehrheitsmeinung („Appellants have not made a ’strong showing that [they are] likely to succeed on the merits‘ of this appeal.“) ist zwar – angesichts dessen, daß der Supreme Court für einen Erfolg der Regierung in der Hauptsache seine Rechtsprechung ändern müßte [*] (was aber weder rechtlich unzulässig noch tatsächlich ausgeschlossen ist) und der Wortlaut der Staatsangehörigkeits-Klausel in der US-Verfassung jedenfalls eher gegen als für die Auffassung der Trump-Regierung spricht – auch nicht abwegig. Aber besonders didaktisch ist es jedenfalls nicht, sich auf diesen einen Satz ohne Begründung zu beschränken…

Weitere Informationen:

Zum erstinstanzlichen Verfahren:

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69561931/state-of-washington-v-trump

Zum Verfahren zweiter Instanz:

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69621321/state-of-washington-et-al-v-trump-et-al

- Motion to Stay Lower Court or Agency Proceedings/Order der Trump-Regierung vom 12.02.2025:

- Antwort darauf vom Appellee State of Washington vom 18.02.2025:

- Supplemental Addendum dazu vom selben Tage:

- Reply to Response to der Trump-Regierung vom 19.02.2025:

- Entscheidung des Appeal Court (einschl. concurring vote von Richterin Forrest) vom selben Tage:

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303/gov.uscourts.ca9.3b7bc70c-6fcb-460e-9232-c6bc8ad16303.21.0_2.pdf (28 Seiten + Anlagen)

Im Gegensatz zu meiner Zustimmung mit skeptischem Unterton gegenüber dem concurring vote von Forrest:

Kyle Cheney / Josh Gerstein, Appeals court deals setback to Trump efforts to immediately end birthright citizenship

https://www.politico.com/news/2025/02/19/trump-birthright-citizenship-appeals-court-00205081 vom 19.02.2025

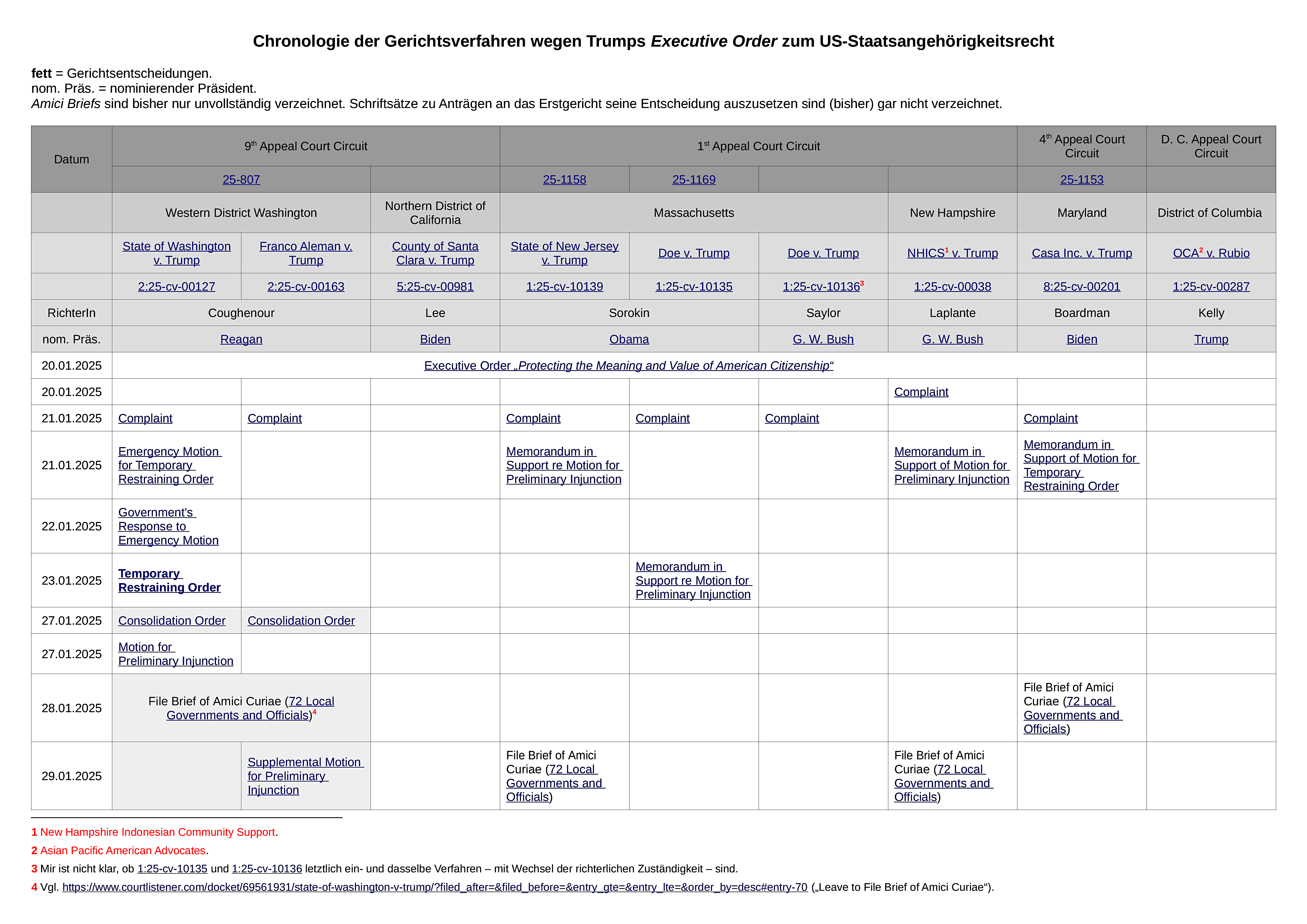

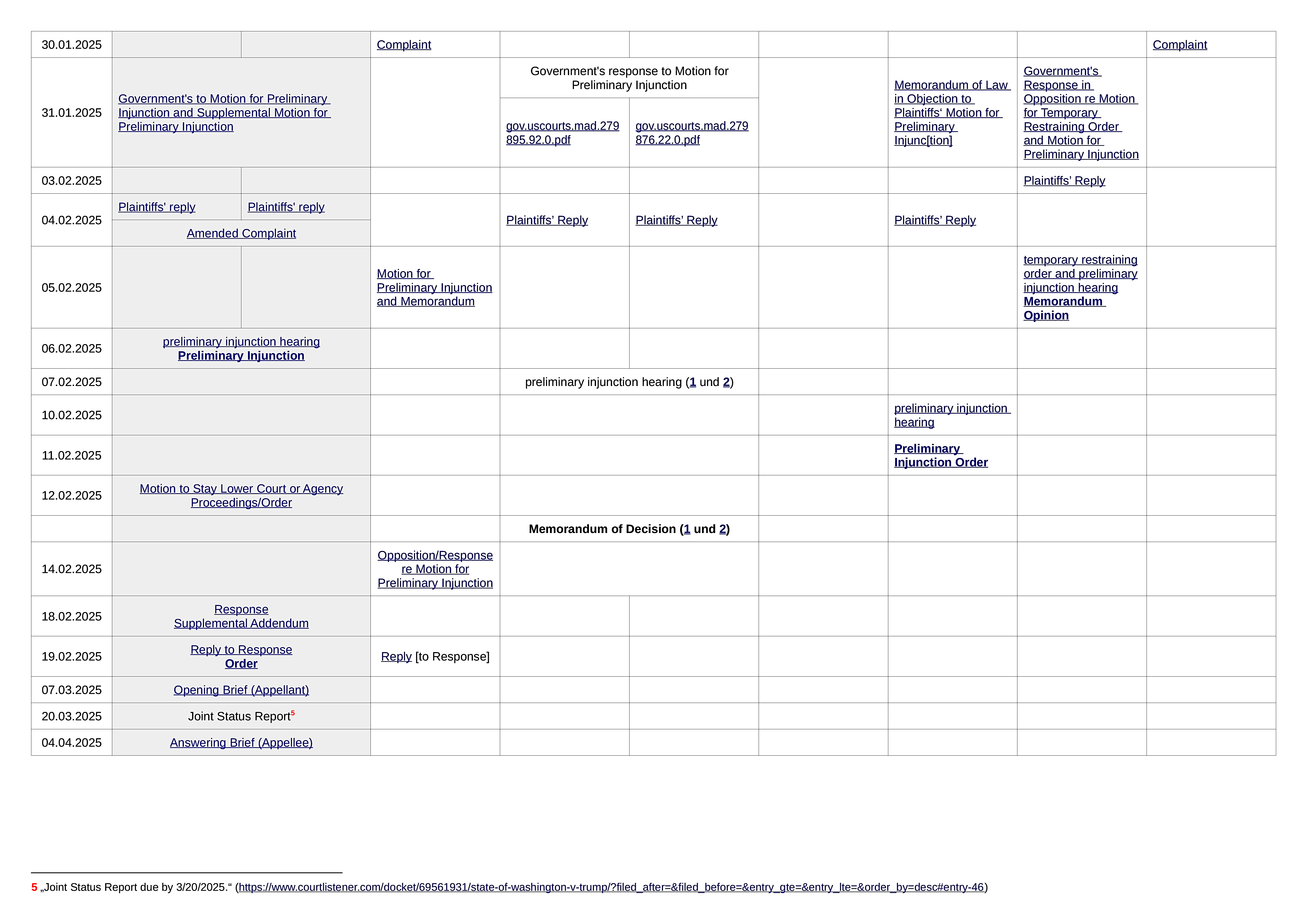

Aktualisierte Chronologie der mir bekannten Gerichtsverfahren zum US-Staatsangehörigkeits-Streit

.pdf-Datei (mit Hyperlinks zu den bisherigen Schriftsätzen und Gerichtsentscheidungen) – DIN A 3 querformatig:

[*] Diese Rechtsprechung betrifft Absatz 1 Satz 1 des 14. Zusatzes zur US-Verfassung:

„All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.“

(https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CDOC-110hdoc50/pdf/CDOC-110hdoc50.pdf, S. 16 [gedruckte Seitenzählung] bzw. 22 [digitale Seitenzählung])

In der von Forrest erwähnten Entscheidung United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, 693 (1898) heißt es dazu an der von Forrest genannten Stelle (S. 693):

„The Fourteenth Amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens, with the exceptions or qualifications (as old as the rule itself) of children of foreign sovereigns or their ministers, or born on foreign public ships, or of enemies within and during a hostile occupation of part of our territory, and with the single additional exception of children of members of the Indian tribes owing direct allegiance to their several tribes. […]. Every citizen or subject of another country, while domiciled here, is [mit den vorgenannten vier Ausnahmen] within the allegiance and the protection, and consequently subject to the jurisdiction, of the United States.“

(United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 [1898], S. 693 der gedruckten bzw. 34 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt)

Und spätere Supreme Court-Entscheidungen liegen auf der gleichen Linie:

„Use of the phrase ‚within its jurisdiction‘ thus does not detract from, but rather confirms, the understanding that the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment extends to anyone, citizen or stranger, who is subject to the laws of a State, and reaches into every corner of a State’s territory. That a person’s initial entry into a State, or into the United States, was unlawful, and that he may for that reason be expelled, cannot negate the simple fact of his presence within the State’s territorial perimeter. Given such presence, he is subject to the full range of obligations imposed by the State’s civil and criminal laws. And until he leaves the jurisdiction – either voluntarily, or involuntarily in accordance with the Constitution and laws of the United States – he is entitled to the equal protection of the laws that a State may choose to establish.“

(Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, [1982], https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep457/usrep457202/usrep457202.pdf, S. 215 der gedruckten bzw. 14 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt)

„Respondents, a married couple, are natives and citizens of Mexico. Respondent husband illegally entered the United States in 1972. Apprehended, he returned to Mexico in early 1974 under threat of deportation. Two months later, he and respondent wife paid a professional smuggler $ 450 to transport them into this country, entering the United States without inspection through the smuggler’s efforts. Respondent husband was again apprehended by INS agents in 1978. At his request, he was granted permission to return voluntarily to Mexico in lieu of deportation. He was also granted two subsequent extensions of time to depart, but he ultimately declined to leave as promised. INS then instituted deportation proceedings against both respondents. By that time, respondent wife had given birth to a child, who, born in the United States, was a citizen of this country.“

(INS v. Rios-Pineda, 471 U.S. 444 [1985], https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep471/usrep471444/usrep471444.pdf, S. 446 der gedruckten bzw. 4 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt)

Sodann noch eine Entscheidung aus dem Jahr 2004:

„This case arises out of the detention of a man whom the Government alleges took up arms with the Taliban during this conflict. His name is Yaser Esam Hamdi. Born in Louisiana in 1980, Hamdi moved with his family to Saudi Arabia as a child. […]. The Government asserts that it initially detained and interrogated Hamdi in Afghanistan before transferring him to the United States Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay in January 2002. In April 2002, upon learning that Hamdi is an American citizen, authorities transferred him to a naval brig in Norfolk, Virginia; where he remained until a recent transfer to a brig in Charleston, South Carolina.“

(Hamdi et al v. Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense, et al., 542 U.S. 507 [2004], https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep542/usrep542507/usrep542507.pdf, S. 510 der gedruckten bzw. 4 der digitalen Seitenzählung; Hv. hinzugefügt)

Laut John Eastman (siehe zu diesem meinen Artikel vom 30.01.2025, S. 7 f., FN 10) – ein Gegner der bisherigen Rechtsprechung – war Hamdis Mutter, als Nadia Hussen Fattah in Taif (Saudi Arabien) geboren worden und Hamdis Vater „a native of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and still a Saudi citizen, […] residing at the time [von Hamdis Geburt] in Baton Rouge [= die Hauptstadt von Louisiana] on a temporary visa to work as a chemical engineer on a project for Exxon.“ (https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2741&context=lawreview, S. 955 f. bzw. 2 f.)

Beide Elternteile waren also anscheinend nicht US-StaatsbürgerInnen und nur vorübergehend rechtmäßig („temporary visa“) in den USA und gingen mit ihrem Sohn alsbald nach der Geburt („as a child“) zurück nach Saudi-Arabien zurück. Dennoch war jedenfalls für die Supreme Court-Mehrheit von 2004 klar, daß Hamdi US-Staatsbürger war.

Weiteres Verfahren:

New York Immigration Coalition v. Donald J. Trump (1:25-cv-01309)

District Court, S.D. New York

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69638232/new-york-immigration-coalition-v-donald-j-trump/.