In Gerichtsverfahren wegen des Streits um die Neubestimmung der US-Staatsangehörigkeit durch Präsident Trump reichte die US-Regierung am Freitag mehrere neue Schriftsätze ein. Zu dem Verfahren Casa Inc. v. Trump (8:25-cv-00201) vor dem District Court Maryland schrieb ich am Freitag:

„Den AnwältInnen der Plaintiffs wird Wochenendarbeit bevorstehen, denn bereits am Mittwoch (05.02.2025) wird in dem Verfahren eine mündlich Verhandlung, zu der es vielleicht einen audio stream geben wird (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698.36.0_1.pdf), stattfinden; eine schriftliche Antwort auf den heutigen Regierungs-Schriftsatz wird vorher fertig werden müssen.“

Jetzt ist die 19-seitige Antwort da; auf S. 4 der gedruckten bzw. 6 der digitalen Seitenzählung bis S. 14 bzw. 16 befindet sich der Abschnitt II. „The Executive Order Violates the Fourteenth Amendment“. Soweit sich die Plaintiffs (KlägerInnen/AntragstellerInnen) dort auf konkrete Stellen des Regierungsschriftsatzes von Freitag für das dortige Verfahren beziehen, zitiere ich im folgenden zunächst die jeweiligen Stellen aus dem Regierung-Schriftsatz und so dann die diesbezügliche Antwort von heute:

I. Sind die in Bezug auf Trumps Executive Order relevanten Stellen der Wong Kim Ark-Entscheidung des US-Supreme Court bloß nebenbei Gesagtes oder sind sie tragende Gründe der damaligen Entscheidung?

1. a) Die Trump-Regierung schrieb am Freitag: „No doubt some statements in Wong Kim Ark could be read to support Plaintiffs’ position.“ (Wong Kim Ark war Partei eines Verfahrens vor dem US-Supreme Court; die Parteinamen werden, wie hier, auch – alternativ zu genauen Fundstellen-Angaben – als Bezeichnungen für die Gerichtsentscheidungen in den jeweiligen Verfahren verwendet.) Aber

„Wong Kim Ark never purported to overrule any part of Elk [= eine vorhergehende Supreme Court-Entscheidung], however, and the Supreme Court has previously (and repeatedly) recognized Wong Kim Ark’s limited scope. In one case, the Court stated that:

[t]he ruling in [Wong Kim Ark] was to this effect: ‚A child born in the United States, of parents . . . who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen.‘

Chin Bak Kan v. United States, 186 U.S. 193, 200 (1902) (emphasis added; citation omitted). In another, the Court cited Wong Kim Ark for the proposition that a person is a U.S. citizen by birth if ‚he was born to [foreign subjects] when they were permanently domiciled in the United States.‘ Kwock Jan Fat v. White, 253 U.S. 454, 457 (1920) (citation omitted).“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698.40.0.pdf, S. 23 f. der gedruckten bzw. S. 25 f. der digitalen Seitenzählung )

(„Chin Bak Kan v. United States, 186 U.S. 193, 200 (1902)“ und ähnliche Fundstellen-Angaben verweisen auf Entscheidungen des US-Supreme Court; wo sie zu finden sind, hatte ich in meinem ersten Artikel zum US-Staatsangehörigkeits-Streit erklärt [siehe dort, Abschnitt VI. 4. b)].)

b) Schon vor ihren Schriftsätzen von Freitag hatte die Trump-Regierung in einem Schriftsatz für eines der Parallel-Verfahren argumentiert:

„Plaintiffs rely1 on the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), but they overread that case. Wong Kim Ark involved a person who was born in the United States to alien parents who, at the time of the child’s birth, ‚enjoy[ed] a permanent domicile and residence‘ in the United States. Id. at 652. The Court explained that the ‚question presented‘ concerned the citizenship of ‚a child born in the United States‘ to alien parents who ‚have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States.‘ Id. at 653. Answering that question, the Court held that ‚a child born in the United States‘ to alien parents who ‚have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States‘ ‚becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States.‘ Id. at 705. Despite some broadly worded dicta2, the Court’s opinion thus leaves no serious doubt that its actual holding concerned only children of permanent residents. The EO is fully consistent with that holding. See, e.g., Citizenship EO § 2(c) (‚Nothing in this order shall be construed to affect the entitlement of other individuals, including children of lawful permanent residents, to obtain documentation of their United States citizenship.‘ (emphasis added)).“

(http://blogs.taz.de/theorie-praxis/files/2025/01/gov.uscourts.wawd_.343943.36.0_1.pdf, S. 13 f.; Hyperlinks hinzugefügt)

2. Darauf antworten nun heute Casa, Inc. und die anderen Plaintiffs des ‚Maryland-Verfahrens‘:

„Defendants [= verschiedene Stellen der US-Regierung] concede that ‚[n]o doubt some statements in Wong Kim Ark could be read to support Plaintiffs’ position,‘ but dismiss those statements as dicta. U.S. Br. 23-24. But a court’s reasoning that directly supports its holding is not dicta. Payne v. Taslimi, 998 F.3d 648, 654-55 (4th Cir. 2021). To the contrary, the Supreme Court’s authoritative interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment was an integral part its conclusion. A lower federal court ‚cannot ignore the Supreme Court’s explicit guidance simply by labeling it ›dicta.‹‘ Hengle v. Treppa, 19 F.4th 324, 346 (4th Cir. 2021). ‚Respect for the rule of law demands nothing less: lower courts grappling with complex legal questions of first impression must give due weight to guidance from the Supreme Court, so as to ensure the consistent and uniform development and application of the law.‘ Manning v. Caldwell ex rel. City of Roanoke, 930 F.3d 264, 282 (4th Cir. 2019) (en banc).“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698.46.0.pdf, S. 5 f. bzw. 7 f.)

In Fußnote 3 setzen sie noch hinzu:

„Wong Kim Ark does not stand alone: the Supreme Court has consistently adhered to this understanding of the Citizenship Clause. E.g., United States ex rel. Hintopoulos v. Shaughnessy, 353 U.S. 72, 73 (1957) (noting that a child born in the United States was ‚of course, an American citizen by birth,‘ despite his parents’ ‚illegal presence.‘); see also INS v. Errico, 385 U.S. 214, 215–16 (1966); INS v. Rios-Pineda, 471 U.S. 444, 446 (1985).“

II. Noch einmal: Was bedeutet die Formulierung „subject to the jurisdiction [of the United States]“ in der Staatsangehörigkeits-Klausel der US-Verfassung?

1. Wie schon mehrfach geschrieben, lautet der Satz in der US-Verfassung, der die Staatsangehörigkeit regelt:

„All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.“

(https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CDOC-110hdoc50/pdf/CDOC-110hdoc50.pdf, S. 16 bzw. 22)

2. Zur Interpretation der Formulierung „subject to the jurisdiction thereof“ schrieb die US-Regierung am Freitag – unter Berufung auf die Wong Kim Ark-Entscheidung des US-Supreme Court – zunächst:

„Instead of equating ‚jurisdiction‘ with regulatory authority, the Supreme Court has held that a person is ’subject to the jurisdiction‘ of the United States under the Citizenship Clause if he is born ‚in the allegiance and under the protection of the country.‘ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 693. That allegiance to the United States, the Court has further held, must be ‚direct,‘ ‚immediate,‘ and ‚complete,‘ unqualified by ‚allegiance to any alien power.‘ Elk, 112 U.S. at 101-02.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698.40.0.pdf, S. 10 bzw. 12 unten / S. 11 bzw. 13 oben)

3. Darauf antworten die Plaintiffs heute:

„Defendants’ [= Der US-Regierung] reading of ’subject to the jurisdiction‘ of the United States is internally inconsistent, and impossible to square with either constitutional text or Wong Kim Ark. Defendants at times argue that a person is covered by the Citizenship Clause only when they have ‚complete‘ allegiance to the United States, ‚unqualified by ›allegiance to any alien power.‹” U.S. Br. 11 (quoting Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94, 101-02 (1884)). Such a test does not appear in the Citizenship Clause’s text, which asks only whether a person is ’subject to the jurisdiction‘ of the United States—not whether a person is subject to the ‚exclusive jurisdiction‘ or possesses some particular quantum of allegiance. See Michael Ramsey, Originalism and Birthright Citizenship, 109 Geo. L. J. 405, 460 (2020) (discussing the original meaning of ’subject to the jurisdiction‘ of the United States). If complete allegiance were the test, then Wong Kim Ark’s parents (like most foreign nationals) would not meet it, as they were ’subjects of the emperor of China,‘ and undoubtedly owed a measure of allegiance to China. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 652; see also U.S. Br. 18 (‚The phrase, ›subject to its jurisdiction,‹ was intended to exclude from its operation . . . citizens or subjects of foreign States born within the United States‘ (emphasis supplied by United States) (quoting Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36, 73 (1873)). But this is not the test, and it is flatly inconsistent with Wong Kim Ark to insist upon it.4 169 U.S. at 694 (rejecting the argument that ‚the fourteenth amendment of the constitution excludes from citizenship the children born in the United States of citizens or subjects of other countries‘).

Elsewhere, Defendants try to temper the radical consequences of their revisionist account by suggesting that a person owes complete allegiance to whatever jurisdiction they are domiciled in, which would exclude temporary visitors. U.S. Br. 18-19.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698.46.0.pdf, S. 6 bzw. 8 bis S. 7 bzw. 9)

4. Auf S. 18 bzw. S. 20 des Regierungs-Schriftsatzes von Freitag hieß es:

„Contemporary commentators expressed similar views. See, e.g., Hall, supra, 236-237 (‚In the United States it would seem that the children of foreigners in transient residence are not citizens.”); Alexander Porter Morse, A Treatise on Citizenship 248 (1881) (‚The words ‘subject to the jurisdiction thereof’ exclude the children of foreigners transiently within the United States.‘).

The Supreme Court of New Jersey similarly linked birthright citizenship with parental domicile in Benny v. O’Brien, 32 A. 696 (N.J. 1895). In a passage that was later quoted in Wong Kim Ark, the court interpreted the Citizenship Clause to establish ‚the general rule that, when the parents are domiciled here, birth establishes the right of citizenship.‘ Id. at 698 (emphasis added). And it explained that the Citizenship Clause’s jurisdictional element excludes ‚those born in this country of foreign parents who are temporarily raveling here” because ‚[s]uch children are, in theory, born within the allegiance of [a foreign] sovereign.‘ Id.“

5. Darauf antworten die Plaintiffs heute:

„here is little support for Defendants’ gloss, and it is hard to square with statements elsewhere in their brief questioning the citizenship of children born in the United States to foreign nationals. A noncitizen present in the United States is subject to this Nation’s jurisdiction while they are here, regardless of the duration of their stay. And again, basing the test on allegiance is inconsistent with Wong Kim Ark, given that no one doubted that Wong Kim Ark’s parents owed at least some measure of allegiance to China. 169 U.S. at 652. Defendants’ shifting and idiosyncratic views on the nature of allegiance underscore how far they have strayed from the constitutional text, which asks simply whether a person is ’subject to the jurisdiction‘ of the United States.“

In einer Fußnoten zum ersten Halbsatz des Zitates heißt es außerdem:

„As Secretary of State Daniel Webster observed, a person’s duty to the local sovereign exists ‚independently of a residence with intention to continue such residence, independently of any domiciliation.‘ 6 Daniel Webster, Works of Daniel Webster 526 (1851).“

III. Die Ausnahme bezüglich der native Americans (bzw. bestimmter native Americans; siehe dazu bereits in meinem Artikel von Donnerstag [30.01.2020], S. 12 f. in und bei Fußnote 20]

1. Im Regierungs-Schriftsatz von Freitag hieß es

- auf S. 9 bzw. 11 unten:

„Most importantly, Plaintiffs’ understanding of the term ‚jurisdiction‘ conflicts with Supreme Court precedents identifying the categories of persons who are not subject to the United States’ jurisdiction within the meaning of the Citizenship Clause. For example, the Supreme Court has held that children of members of Indian tribes, ‚owing immediate allegiance‘ to those tribes, do not acquire citizenship by birth in the United States. Elk, 112 U.S. at 102; see Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 680-82. Yet members of Indian tribes and their children are plainly subject to the United States’ regulatory power.“

und

- auf S. 13 bzw. 15:

„the [Supreme] Court has held that certain children of members of Indian tribes are not subject to U.S. jurisdiction in the necessary sense because they ‚owe[] immediate allegiance to their several tribes.‘ Elk, 112 U.S. at 99.“

2. Darauf antworten die Plaintiffs auf S. 7 f. bzw. 9 f. ihres heutigen Schriftsatzes:

„Defendants’ reliance on the exception for Indian tribes discussed in Elk v. Wilkins, is misplaced. U.S. Br. 9-10, 12 [gemeint zu sein scheint vielmehr S. 13]. To start, Defendants’ argument ignores the unique history of tribal sovereignty and the federal government’s relationship with Indian tribes, which prevents extrapolation to other areas. See Haaland v. Brackeen, 599 U.S. 255, 307 (2023) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (noting the need to take ‚a full view of the Indian-law bargain struck in our Constitution‘). The Framers of the Fourteenth Amendment excluded Indian tribes from the Citizenship Clause in order to endorse a strong vision of tribal sovereignty that resisted federal and state power over tribes. Gerard N. Magliocca, Indians and Invaders: The Citizenship Clause and Illegal Aliens, 10 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 499, 515-22 (2008). It is ‚conceptually incoherent‘ and historically confused to use the exception for tribal members as an open door to create other exceptions to the Citizenship Clause. Id. at 502. And the Supreme Court in Wong Kim Ark already squarely rejected an attempt, like that offered by Defendants here, to overread Elk and divine from the exception for Indian tribes a broader rule excluding children born to foreign parents. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 682 (‚The decision in Elk v. Wilkins concerned only members of the Indian tribes within the United States, and had no tendency to deny citizenship to children born in the United States of foreign parents of Caucasian, African, or Mongolian descent, not in the diplomatic service of a foreign country.‘). Put simply, nothing in history or precedent justifies Defendants’ attempt to equate foreign nationals and tribal members.“

IV. Auf Rechts-, Gesetzgebungs- und Rechtsanwendungsgeschichte bezogene Erwägungen

Es folgt dann auf den S. 8 bzw. 10 bis S. 11 bzw. 13 ein Abschnitt „History Cuts Decisively Against Defendants’ Position“, der nur teilweise direkt auf bestimmte Stellen des Regierungs-Schriftsatzes von Freitag antwortet. Ich komme auf diesen Abschnitt vielleicht später genauer zurück.

V. Weiteres

Es folgen dann noch die Abschnitte II. C. „Interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment to Include a Domicile Requirement Would Not Justify the Executive Order“ und II. D. „The Executive Order Also Violates Federal Statutes“.

Abschnitt II. D. sei hier ausgespart, weil politisch – angesichts der gegenwärtigen republikanischen Mehrheit sowohl im Senat als auch im RepresentantInnenhaus – wenig gewonnen wäre, wenn das, was Trump (vielleicht) nicht durch Verordnung einführen darf, der Kongreß durch Gesetz einführen dürfte.

Abschnitt II. C. des heutigen Plaintiffs-Schriftsatzes besteht aus drei Absätzen, die folgendermaßen lauten:

„As explained, Defendants’ argument that the Citizenship Clause requires parental domicile is wrong as a matter of text, history, and precedent. But remarkably, even if the Defendants’ domicile argument were accepted, it would fail to justify the Executive Order. Many, if not most, of the parents covered by the Executive Order are domiciled in the United States.

Domicile is based on residence and the ‚intention of making it the home of the party.‘ Story, supra, § 44, at 42. ‚If it sufficiently appear that the intention of removing was to make a permanent settlement, or for an indefinite time, the right of domicil is acquired by a residence even of a few days.‘ The Venus, 12 U.S. (8 Cranch) 253, 279 (1814). Undocumented immigrants often spend years, if not decades, in the United States. They travel to the United States not for a temporary visit but to make the United States their home. Defendants posit that such immigrants ‚have no right even to be present in the United States, much less a right to make lawful residence here,‘ U.S. Br. 14, but lawful status has nothing to do with domicile. E.g., Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 227 n.22 (1982) (explaining that ‚illegal entry into the country would not, under traditional criteria, bar a person from obtaining domicile within a State‘); Clement L. Bouvé, A Treatise on the Laws Governing the Exclusion and Expulsion of Aliens in the United States 340 (1912) (an immigrant who ‚enter[s] in violation of the Immigration acts . . . [and] takes up his residence here with intent to remain has done all that is necessary for the acquisition of a domicile‘).

The same is true for many of the others covered by the Executive Order. In many cases, a person seeking asylum or subject to temporary protected status will possess the necessary intent to remain required by the definition of ‚domicile.‘ The vast majority of ASAP and CASA members cited in Plaintiffs’ complaint, for example, have lived in the United States for years. Other individuals whose children would be denied U.S. citizenship under the Executive Order, such as those enrolled in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, have similarly lived in the United States for decades—many for most of their lives. The notion that they are not properly considered ‚domiciled‘ in the United States defies both logic and precedent. Even on Defendants’ own terms, the Executive Order fails.“

(https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698/gov.uscourts.mdd.574698.46.0.pdf, S. 12 f. bzw. 14 f.)

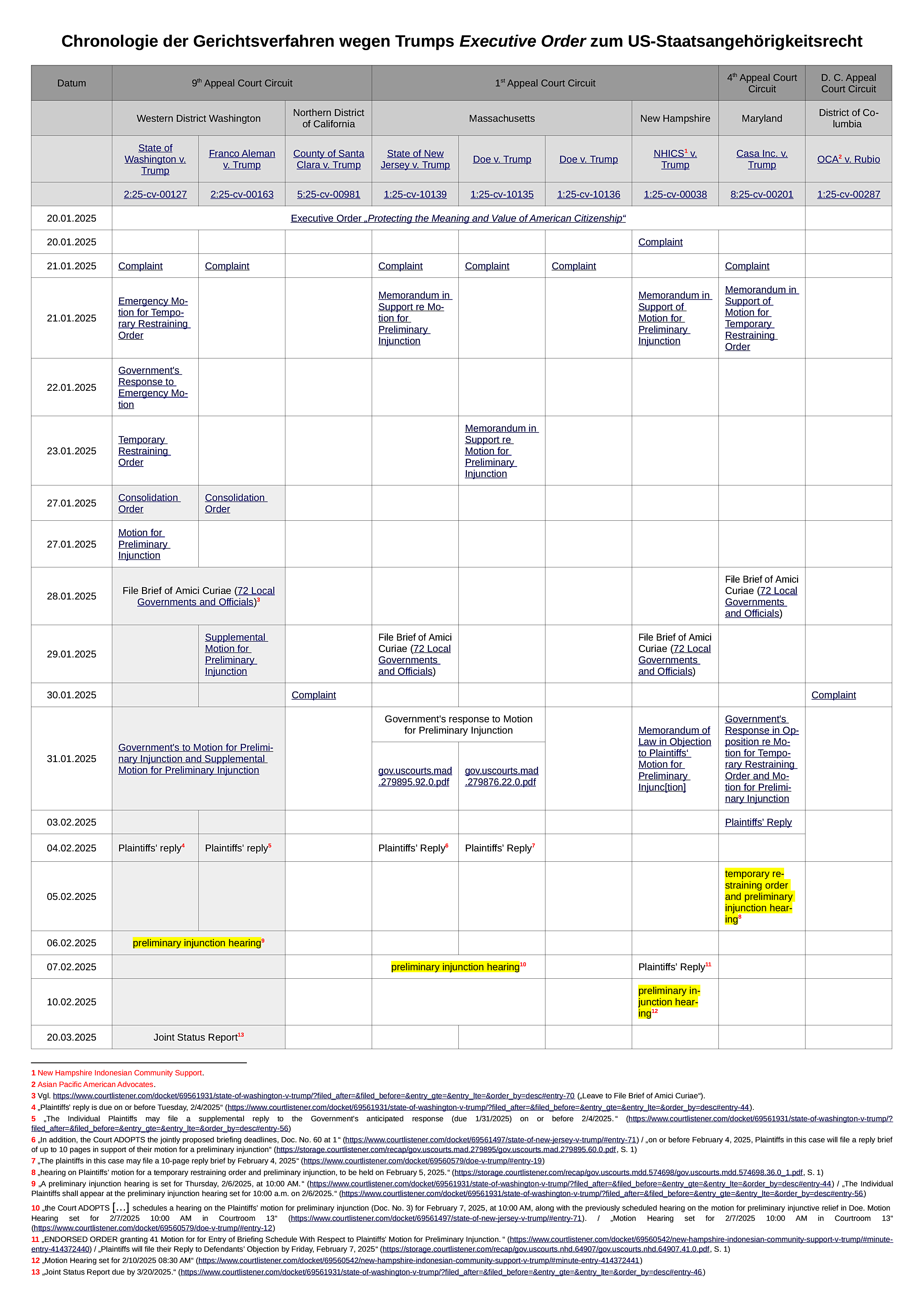

VI. Hier noch mal die Chronologie der verschiedenen Verfahren zum US-Staatsangehörigkeits-Streit

Die Chronologie rfordert ein großes Display oder einen DIN A 3-Drucker, um sie bequem lesen zu können; die .pdf-Datei enthält Hyperlinks zu den Schriftsätzen.

http://blogs.taz.de/theorie-praxis/files/2025/02/Chronologie-US-Staatsangehoerigkeitsrecht-2.pdf

1 Im Antrag der Bundesstaaten hieß es: „This understanding of the Citizenship Clause is cemented by controlling U.S. Supreme Court precedent which, more than 125 years ago, confirmed that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees citizenship to the children of immigrants born in the United States. United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, 654 (1898). As the Supreme Court explained: ‚Every citizen or subject of another country, while domiciled here, is within the allegiance and the protection, and consequently subject to the jurisdiction, of the United States.” Id. at 693 (emphasis added). […]. Consequently, the Court held that a child born in San Francisco to Chinese citizens was an American citizen by birthright. Id. at 704. In reaching this conclusion, the Court reasoned that the Fourteenth Amendment ‚affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens.‘ Id. at 693 (emphasis added).“ (https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.wawd.343943/gov.uscourts.wawd.343943.10.0_1.pdf, S. 12 [der gedruckten Seitenzählung bzw. 18 [der digitalen Seitenzählung]; Hyperlink hinzugefügt)

2 Lat. obiter dicta (Plural; obiter dictum [Singular]) = nebenbei Gesagtes; Äußerungen eines Gerichts in einer Entscheidung, die über die Beantwortung der Frage, die es zu entscheiden hat, hinausgeht. Vgl. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/obiter_dicta und https://jurawelt.com/rechtslexikon/o/obiter-dictum-vs-ratio-decidendi-bedeutung/.